My parents moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1984 from Ahmadabad, India, to attend Eastern Michigan University, a school they had chosen randomly from a decade-old college brochure collecting dust at their undergraduate library in India. Like many others, my parents faced discrimination, poverty and sickness, but eventually my father accepted his first job at Ford Automotive back when Detroit proudly called itself Motor City. I was born shortly afterward in 1989.

On the Tuesday of election night, as I saw Michigan turn red on the Jumbotron, I couldn’t help but feel like the story I’m about to tell you was in threat of disappearing with all the other millions of immigrant stories. My parents, my childhood, my upbringing and all that has brought me to this defining moment are now fading away like so many forgotten dreams. I tell my story to you, reader, to revolt against its erasure — its clinical bleaching. I also tell the story for myself, to retrace my bread crumbs so I can figure out what to do next.

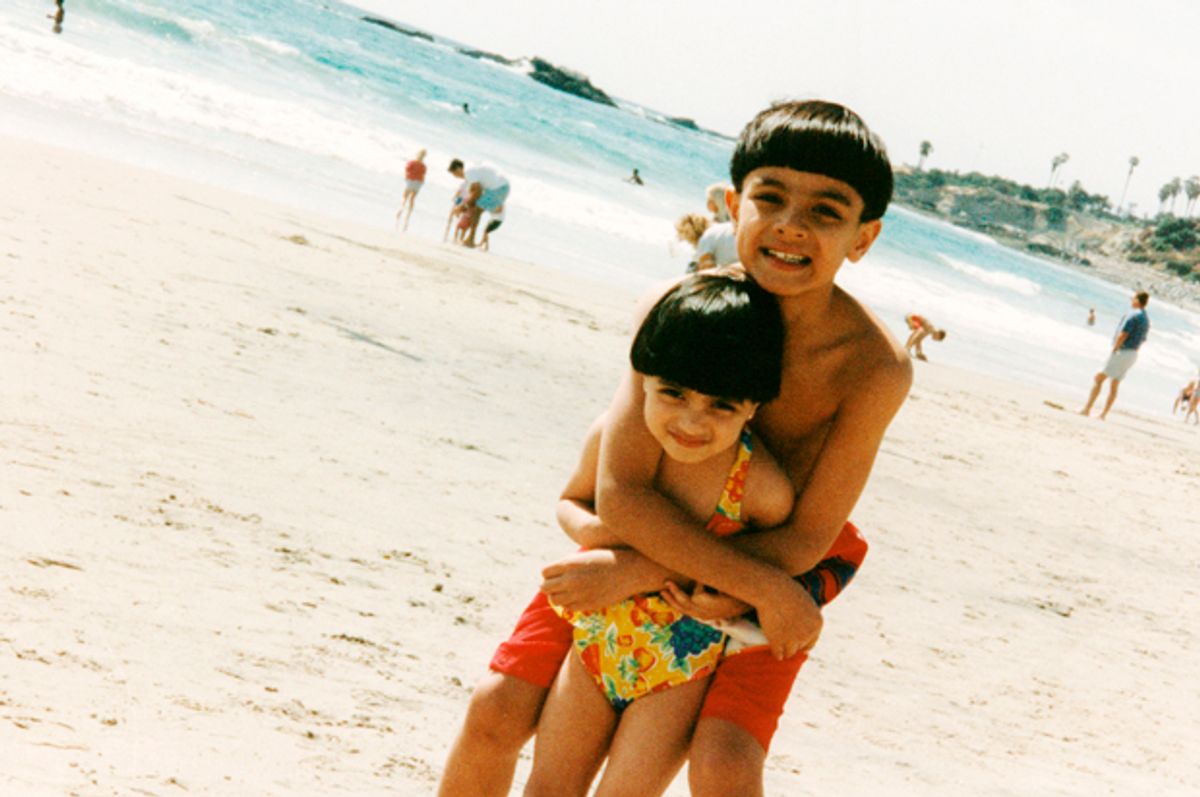

For as long as I can remember, my existence has skated in between two incongruous worlds. In one, I am an American, constantly in search of the American Dream, born in the USA's industrial heartland and raised on ’90s pop culture — "Rocko’s Modern Life" cartoons and Macaulay Culkin movies — and Thanksgiving dinners. In the other, I am Indian, the son of immigrants, inextricably linked to the subjugation of my ancestors, rooted to an ancient land in a new world and raised on Desi culture — "Amar Chitra Katha" comic books and Sharukh Khan movies — and Indian food. Oh man, Indian food.

When I was a young boy in California — my family had since uprooted itself to California — my mother and father, fearing my American upbringing was whitewashing the Indian off me, forced me to join an after-school Hindu program called Balvihar. That may have been true, but at the age of 8 or 9, laboring through yoga postures in white pajamas at the crack of dawn seemed to me the furthest thing from a good time.

Still, I had no choice in the matter. It started as expected: I learned about cultural traditions and ceremonies through forced group exercises and rote memorization, and my teacher’s voice had the ability to induce immediate slumber. It was only a few years later, after I had graduated from the youth program, that a few of us older kids joined a weekly advanced group at the same teacher’s house. We initially accepted her olive branch with the cruel irony of adolescence, but as the class progressed, we all became enthralled by the higher concepts of our culture’s philosophy. So thank you, Mom and Dad.

It was about this time that I was reminded of a concept called maya, which means “illusion of truth.” I remembered its function in mythology: Gods used it like a super power to trick humans into believing truths that were purely illusions. Now we were learning about the journey of the earliest Vedic philosophers who had begun to ponder the true extent of maya’s power over 2,000 years ago.

What if maya isn't just a series of tricks that cause momentary lapses in our perception but one massive illusion that shrouds everything — the very fabric of our realities? In this context, the true meaning of maya ripples beyond the realm of magic and into a fundamental theory about the nature of our existence. The idea seemed to both elude me and entice me, attractive in its intangible mystery. In what way was our perception an illusion? The phrase “illusion of truth,” seemed simple enough, but its full dimension began to take shape only when our teacher, who I now consider to have been my most important mentor, explained the concept to me via a simple thought experiment:

I was asked to think of two ants crawling forward in space. From above, one can see the ants’ journey in the context of the world around them. Let’s say the ants are climbing up a rope hanging from an extremely large jungle gym — on a rope they will not be able to top before their deaths.

Despite the existence of a greater reality, the ants are limited in their senses of observation and they perceive life as just one infinite, immobile rope, which in reality is definite and bendable. Both are unaware of the existence of the jungle gym, let alone the world beyond the sandbox. Even then the ants may have many opposing opinions about the existence of their shared reality: One may believe highly intellectual ancient ant aliens wove the rope; the other may believe that an ant god placed it there.

Whatever it may be, they differ so much in opinion that they come to blows, eventually killing each other in defense of their “truths” — each nowhere close to reality.

Like the ants, we have flawed senses. Our eyes can only see within a certain range of frequencies. Our ears hear limited pitch. Our noses smell a threshold intensity of aroma, etc. Like the ants, humanity moves forward on a straight line through time, unable to coil or bend it, completely unaware of the world beyond. We all kill one another in defense of our “truths.” But what is “truth”? It’s an impossible infinity we can never reach, just beyond the sandbox.

Long after that class, maya is still the way I cope with the complexities of the world, and so it is supremely bizarre to me that our intellectual standard still divines in the cult of dueling opinions. Understanding the true meaning of our biases is not a worthwhile endeavor. Instead, we reduce impossibly complicated, four-dimensional issues to binary yes and no responses.

We hold our illusions as unequivocal truths without seeing the other side of any argument, so much so that we are willing to fight the other in its defense. Why? Because we are afraid of three words: “I don’t know.” Still, we continue to act on our prejudices, causing catastrophic ripples in the world and universe at large. Doesn’t it make sense that maya is the most logical explanation for our global cognitive dissonance, our shared anger and fear of the unknown? The current state of America and the world is not some sort of spontaneous growth, but rather it is a distortion amplified over decades.

Sometimes it feels like we will never understand one another; that we are just talking simultaneously without actually listening, tweeting 140 characters furiously to retain some recollection of things already lost. At first, I wore this anger like a mask, but, in my grieving for the world, I found peace in the nakedness of the unknown.

Doesn’t it feel comforting to say, “I don’t know”? Try it! Try to acknowledge, for once, that nothing is certain and that we are all united in our complete, humbling, ignorance. Now I dance wildly in a world of ghosts and infinite possibilities, where everything is not true or false but just human. How impossibly simple!

It is the elegance of maya that has drawn me so powerfully to the art of lyricism and fiction. In this medium, maya is dramatic irony. With it, I can create a world where only I know the real truth — where all the characters live like unwitting accomplices to a grander design, bumping into one another, causing interactions that then ripple in their fictional universe.

Some characters are much like me and act as my fictional shadows. Others are entirely different. They come from different backgrounds, pray to different gods, and even enjoy different music! During these exercises in creation, I have become comfortable with these characters whose opinions and biases are different than mine, and in turn, have come to terms with the flaws in my own logic and understanding. Maya has taught me a profound sense of empathy in a very real way. Still, I need to be reminded of its lessons constantly.

Like everyone, I am greatly affected and biased by the experiences that have shaped me. I have spent all of my life straddling two worlds, and it has been hard work keeping the balance equal. I have had to rectify the grave contradictions that exist between their ideals, forced to live in a world without precedent or context — in a gray space where only I can choose my next path.

Still, I am always breaking a few rules from one or the other world at any given time. This has instilled a permanent stain of guilt on my psyche. I consider this shame to be the overarching theme in the narrative of the first-generation Indian-American.

I must admit that this narrative is all I have known, and has irreversibly shaped my liberal political and social choices. I am the first to admit that I surround myself mostly with like-minded individuals, and during this election year, have participated in many feedback-loop conversations, questioning the sanity of the “other side,” wondering how such a large swath of America could be “so stupid.”

This is because I only know MY story. It is the tale of my Indian ancestors, whose generations of oppression and subjugation I had to swallow like an egg without emotion in a class of white faces — a story about an Indian boy, who has spent and continues to spend his whole life attempting to escape the stereotypes of his culture, set by those within and outside of it.

But then I remember maya. I remember empathy. My truth is not the whole truth and is most definitely not someone else’s. I do not know the Trump supporter's story, the one in which the country of his or her ancestors is rocked by globalization and tyrannical capitalism. Where black lives matter but not “Black Lives Matter.” The one where the downtrodden blue-collar white man is the misunderstood, unfairly demonized, protagonist.

I will never fully understand these people, but through maya, I can understand their misunderstanding through my own — their anger through my anger. And you know what? Rage is all the same; it scorches everything in its path, and after everything is gone, there will be no more sides to stand on.

As the haze of Tuesday still twinkles in my eye, I am angrier than ever before. I clench my teeth at the injustices laid down like pillars upon America’s immigrant, black and native nations. I shake at the environmental repercussions of Trump’s choices once in office. I want to shout and scream and call the whole thing off. But we must all breathe. No matter what side you’re on, take comfort in the fact that we will all never understand everything. Hopefully our president-elect can learn from maya the same way we all can.

We cannot allow our stories to fade, reader! For the first time in our careers, we as a band are plunging the mirror inward to share our biases and opinions, both light and dark, so we can continue to let go. “Home of the Strange” is that story. For me, it is that yearning to scrub away my guilt, to be released from the vice of pain and anger, and to commiserate with the downtrodden and misunderstood.

I beseech you to tell your story, for others and yourself. Guide yourself forward by looking back. Realize that we are all products of all the footsteps that have taken us here, and that none of us want them to fade away. I want people to know that my anger is not just immigrant anger, or liberal disillusionment or stupidity, but an anger we all share like fire and have the power to spread or dispel together. I want people to know that it’s OK to not know everything. Maybe that’s the first step toward getting a little closer to understanding one another on this infinite rope we all call our reality.

Shares