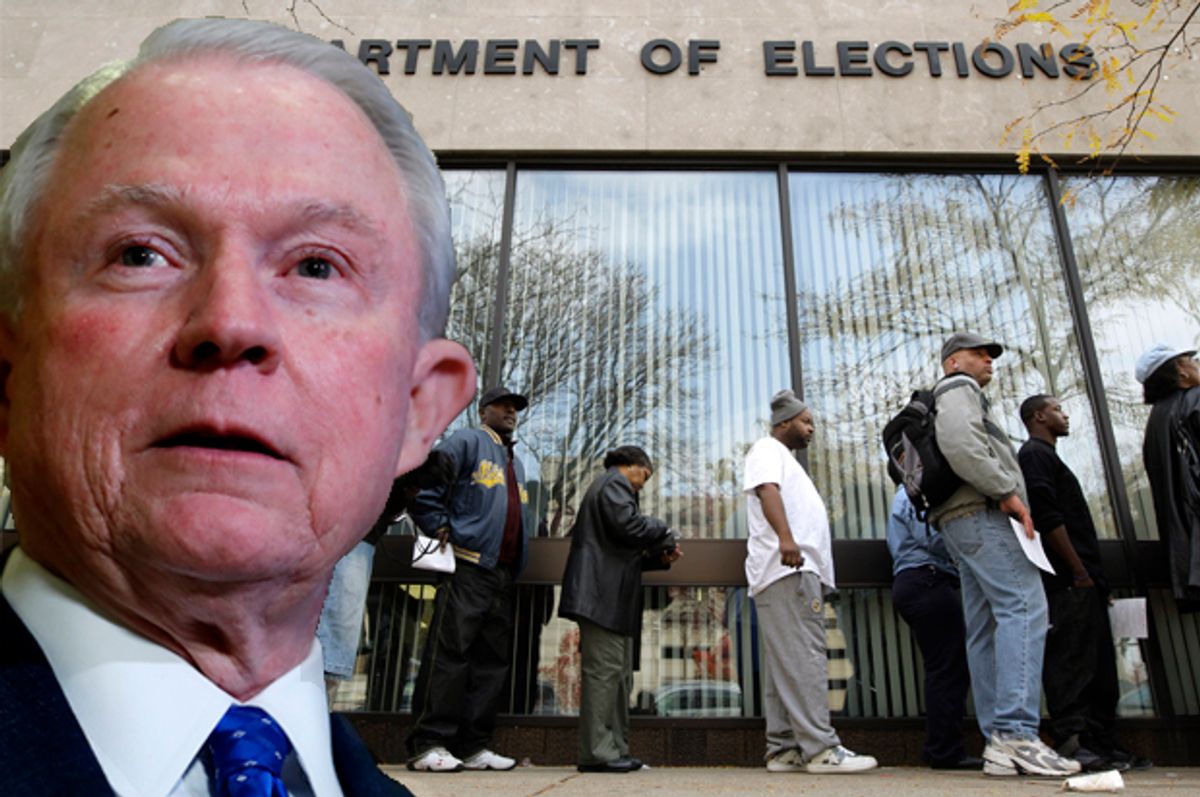

When the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013 with its 5-4 decision in the Shelby County v. Holder case, Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., was pretty excited. In his mind, the bare majority of conservatives on the court had recognized that racism in the South had receded so far, white power structures in Southern states no longer denied African-Americans in those places their right to vote. As Sessions told reporters the day the decision was handed down:

[The decision was] good news, I think, for the South, in that [there was] not sufficient evidence to justify treating them disproportionately. . . . It was passed in direct response to blatant voting rights denial based on the color of one's skin. . . . But now if you go to Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, people aren't being denied the vote because of the color of their skin.

Literally the next day, North Carolina’s Republican-majority legislature, freed from the burden of federal government oversight of the state’s elections, initiated the process of passing several voter restrictions into law, including limiting the early-voting period. Since African-Americans were the state residents most likely to take advantage of early voting, this measure disenfranchised them more than any other voting bloc.

Not only that, but also when defending the law in a lawsuit brought by voting-rights advocates, North Carolina’s attorneys admitted in open court that such disenfranchisement of African-Americans, who vote overwhelmingly for Democrats was precisely the law’s intent.

North Carolina was not the only state to pass voting restrictions that intentionally suppressed the minority vote in 2016. And it was not just Southern states that used the gutting of the Voting Rights Act to pass restrictions that may have made the difference in the presidential race in a couple of states. Thus we can add the country’s failure to protect the voting franchise of its vulnerable citizens to the long, long list of institutional failures — media malpractice, James Comey, the FBI's director, putting both thumbs and an email server on the scales — that allowed Donald Trump to slip into the White House.

But in one further irony, the voter suppression that so helped to get Sessions' blackened, charred heart beating in 2013 has now helped Alabama’s four-term senator and possible descendant of the Lollipop Guild, to the brink of being confirmed as the nation’s 84th attorney general. In this role, he would oversee a Justice Department that has spent the last few years working on lawsuits to fight the very voter-suppression laws that got him there.

Sessions has long been obsessed with the terrible travesty that is black people participating in democracy through the act of voting. He seems to find it unfair that Southern states like his had been singled out for oversight by the Voting Rights Act, which he has referred to as “intrusive” legislation, when, he claimed, discrimination because of skin color is “much more likely” to happen in Northern cities like Philadelphia or Chicago.

To that end, he has long been on a quest to find the voter fraud that he is convinced runs rampant among minorities. As the state attorney general in Alabama in the early 1980s, he infamously prosecuted a group known as the Marion Three for alleged voter fraud. The three — a famous African-American voting rights activist named Albert Turner, his wife Evelyn, and another activist named Spencer Hogue — were charged with 29 felony counts after helping several hundred elderly black voters mail their absentee ballots. A jury needed less than three hours of deliberation to find the trio not guilty on all charges.

Sessions was undeterred, even though the case became an issue for him in 1986, when President Ronald Reagan nominated him for a federal judgeship. His actions against the Marion Three became just one example of his racist attitude that helped sink him at his confirmation hearings in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Over his years in the Senate, Sessions has championed voter ID and other laws designed to subvert minority voting rights while continuing to claim that voter fraud is a major problem nationwide, with no evidence to back him up.

Now, in the wake of the first presidential election after the Shelby County decision, with reports from across the nation of minorities finding themselves disqualified from voting by laws intended to disenfranchise them, Trump has nominated Sessions to oversee a Justice Department whose civil rights division has been fighting these very efforts. It is just one more way Trump is fulfilling his election night promise to be a president for all Americans — provided, I guess, that they have the correct skin color and aren’t too worried about pesky things like their constitutionally guaranteed civil rights.

Shares