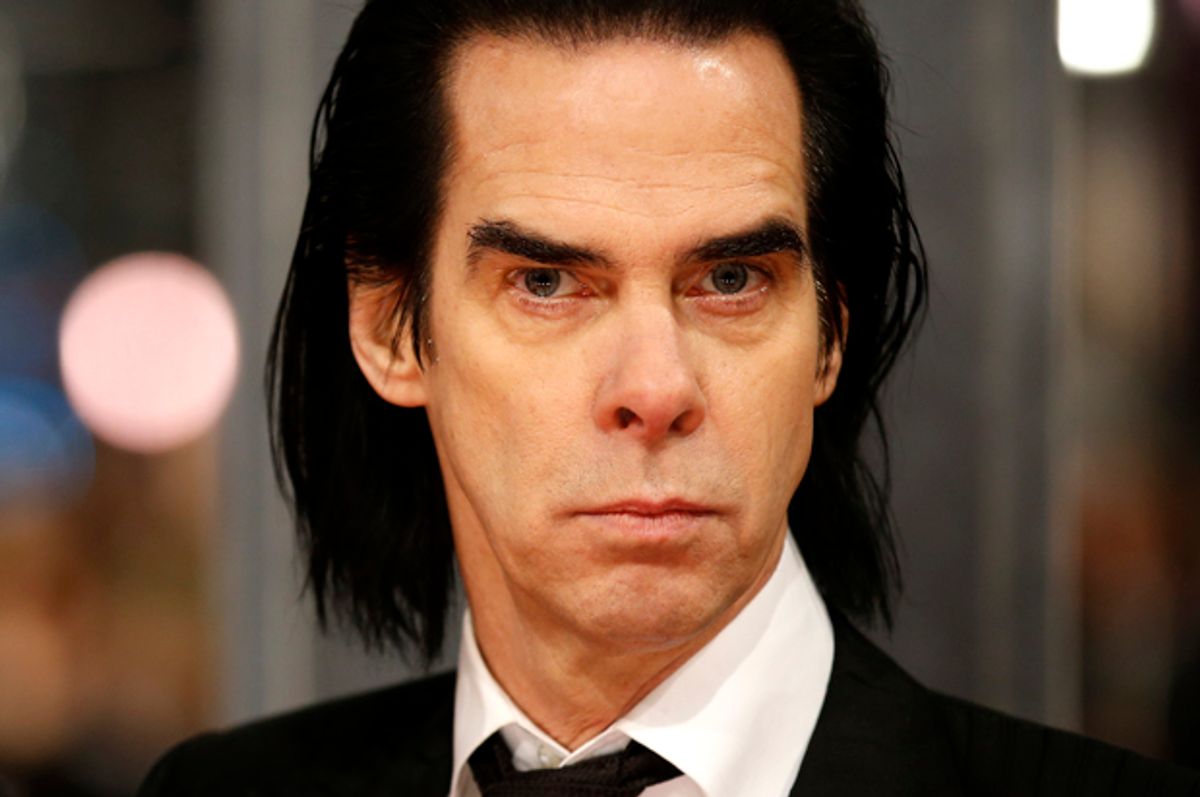

The musician Nick Cave has chronicled death and destruction, whether in gothic tales or American murder ballads, since the early 1980s. But in the summer of 2015, his son Arthur, climbing on chalk cliffs near Brighton, England — where the Cave family lives — fell and later died of his injuries.

Cave has been through a lot in his life, including the death of his father by a car crash when he was 19, years of youthful arrests and decades of heroin addiction. But his son’s death shook him like nothing else.

The Australian film director Andrew Dominik, best known for “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford” and “Killing Them Softly,” has known Cave for almost 30 years. The musician invited Dominik to shoot a film about the making of his new record with the Bad Seeds, “Skeleton Key.”

The ensuing documentary, “One More Time With Feeling.” is both deeply painful and beautifully shot; it opens more widely on December 1.

Dominik spoke to Salon from Los Angeles. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Let’s talk a little about how it started. Did Nick approach you originally for this? What was the original goal for you guys with this documentary?

Well, I think my involvement in it probably started just in the aftermath of Arthur’s death. You know what I mean? Nick was halfway through making a record.

Yeah. So, Nick was deeply shaken up and confused and trying to figure out how to get by.

I just think that he’s living in a new world. . . . Nick’s a public person, but he leads a private life. There’s no way for him to promote that record without discussing the circumstances of the record. It’s not something that he’s prepared to do with a whole bunch of strangers.

Sure. Right.

There’s something about the interview process where the meaning of the thing becomes completely drained, is completely drained out by the repetition. . . . The fact that these things are personal, they’re deeply felt, but as soon as you start performing them.

That’s just par for the course, you know what I mean. And that’s just something that you have to do when you’re trying to sell something. I think in this case, because of Arthur, it was not a situation that he was prepared to place himself in.

The idea of making the film, I think, was to provide Nick a way . . . I mean, he knows he has to address it or stop being a public figure. And I think the instinct behind making the movie was him finding a way to balance those demands created for himself.

You’re both fellow Australians. I imagine you’ve known him for a long time.

Yeah. We’ve been friends. . . . We’ve known each other for 30 years but [I'm] not at all exactly sure when we became friends. We had a girlfriend in common. That’s how we basically first became aware of each other. I mean, I was just a film student and he was like the sort of . . . mystical figure, he was a mythological figure, who was kind of my rival for this girl’s affections. I wasn’t predisposed towards liking Nick Cave. When I heard the records, I was pretty much blown away by them.

This would have been back in the '80s, we’re talking about?

This is ’86, I think. ’86 or ’87.

He used to call up, spoke to [my girlfriend]. We would . . . he and I just started chatting on the phone and we got along, having great conversations. Eventually, over the years, we became friends.

I think he did some works on “Jesse James.” Am I right about that?

Yeah, he did the score.

Right. What a beautiful film.

Well, in this one, you let the death sort of sneak up on us. There’s a lot of different ways you could tell the story. The conventional documentary style would have been very different than what you’ve done. It, sort of, lurks around the edges, or lurks inside Cave, and it stands behind his words, but you’re not explicit, really. You’re certainly not chronological in the telling. What made you want to do it this more elusive kind of way?

Well, I think that the interest in the film. . . . I mean, first of all, this film is designed for a very specific audience.

Right. This is for fans and people who know the story, right?

Nick Cave fans.

Right.

Those people that care about Nick. What they really want to know is how does he feel and that’s really what the film is about. How has this affected his life, you know?

Yeah.

What you see in the movie is a person who is trying to keep moving through life, trying to keep doing the same things that he did before, but he is in a new world. He is trying to make sense of something.

Nick is a person who has dealt with everything while working. Heartbreak becomes grist for the mill. He gets songs out of every situation. In fact, I mean, anybody who writes, I think, probably understands that the way we make sense of life is through fiction. We tell ourselves some little story about something. We can contain it, we compartmentalize it, and we make sense of it. What you see is a person struggling to do that in a situation where that’s really not working. Or is it working? I don’t know.

Right. I’m not sure even he knows it. Yeah, whether it’s working or not.

What I wanted to do was to make a film that gave you the sense of what it was like. You have this movie that’s a collection of moments where you see external activity, but inside him is a kind of a confusion and a lot of conflicting things going on. The film sort of circles around the tragedy and then starts to deal with it head on and the way it happened. There was no sort of plan. We didn’t really know what the film was going to be or . . .

We both knew that it had to deal with Arthur, but we were very reticent, very frightened of the implications of that. Like, what could go wrong with that. It’s approached with a certain amount of caution but with a real desire to be honest.

You say it’s a film aimed at Nick Cave fans, and I think that’s the natural audience. Nick Cave is obviously, a major artist with a substantial following and all of that. I also think it’s a movie about grieving and death in general. Which, this year, with people like Bowie, Prince, the Irish writer William Trevor, Leonard Cohen, Sharon Jones, just an endless list of loss this year — George Martin.

So the movie is about death and grieving, but it’s also about art and creativity in general and the relationship between the creative impulse and tragedy, sorrow and bad shit happening.

I’m a moderate Nick Cave fan. I’m not a zealous Nick Cave fan. Among Australian bands, I’m more a Go-Betweens kind of guy. But I find this film quite moving because it’s more than just a film about Nick Cave.

I’m sure.

Yeah, does that make any sense?

I think anyone with a pulse would be able to get a feeling of it, but that’s not the audience it was made for —

Right. Right.

If people aren’t Nick Cave fans, they should be.

Well, there’s a wonderful sequence in here where Cave says something like “life is not a story” and goes on a sort of riff about that. I think you challenged him and pushed him a little bit on it. Tell me what you think he was getting at there.

Well, I think that what Nick is saying is just that the only meaning in life is the meaning we bring to it. I think he’s saying we live in a chaotic universe that we’re constantly trying to bring a narrative shape to. That narrative shape is not a real meaning. It’s just a projected meaning.

He’s right. I think that he is abandoning narrative and songwriting — because he realizes that there is a way to get in further — and getting close to a kind of a raw experience, I guess. What I was trying to say is just that I think that everybody, no matter who you are — as we’re getting older, all lives are the same. All lives eventually are going to deal with decay.

Yeah, right. Well, it’s an ashes-to-ashes, dust-to-dust kind of thing. And there is that moving passage where he talks about how much older and older-looking he’s gotten just in the last year.

The young feel life is an adventure story. I think the middle aged see life as a kind of tragedy, with unfulfilled opportunities. I think that the elderly realize that there’s no difference between their successes and their failures.

Interesting.

That life ultimately is something that is beyond all of that stuff, which I think comes clearer as you get . . . well, hopefully it comes clearer to you as you get older.

Mm-hmm. Right.

We’re all going to die.

Yeah, well, that’s for sure.

How old are you?

I am 47 and I just lost my dad this year, in addition to all this other bullshit. So thinking about death a lot these days.

Yeah. Well, you’re at an age where you realize that time is moving a lot quicker than it used to. You’re at an age where you realize that you’re not going to be waking up in the morning feeling better. It’s just going to get . . . I mean, look: Arthur has just gone ahead of all of us. We’re all going to die.

Right.

I think the older we get, the more grief is going to find its way into our lives and we see that it’s not abnormal to experience these shocks. But the kind of loss that Nick has suffered is an abnormal one. The grief is something that we’re all going to experience and I think it’s very important to deal with it in a healthy way.

Yeah, sure.

I think that he’s doing a really remarkable job of . . . I mean, I don’t know if they are, dude. I mean it’s just a fucking, massive fucking blow, and you just got to keep going.

Yeah. Well, let’s talk for a second about the way you made the film. This is black and white. Most of it is very intimate. There’s a lot in the recording studio. The interviews with Nick are often in a moving car. You’ve got a 3-D version of it. Why did you make these sort of technical and aesthetic decisions?

Well, I wanted to make a film that you could sink into because I knew the film wasn’t going to have a traditional narrative structure. It wasn’t going to function on that level. It would be like a poem and I feel like 3-D switches off the plot-following part of . . . it switches off the pattern-recognition part of your brain, which is what’s required to follow a plot. I just wanted to create something that you could experience. That’s the reason for 3-D and then black and white has a certain aesthetic distance, which I like. I felt like he’s in a new world.

These aesthetic choices give you a way to see the world with new eyes. When you’re watching a world in black and white, you see it all again. You see it all over again, in a way that you can’t see things in color. There’s that. Also, dealing with the technology is difficult. Black and white reveals truth. I think it reveals character anyway.

Right. Well, part of what’s interesting about your movie, too, is that Cave’s work was already considered pretty gloomy, and he’s always written very eloquently about death and tragedy and the dark side of life, and now he has something that’s truly tragic, dark and deathlike. I wonder if you’re a longtime fan of sad songs, depressing movies, if you think if that sort of work is important and soulful.

As opposed to what?

Happy music, and cheery films, and . . . you know.

What’s an example of like a cheery film?

Frank Capra, most American movies . . .

Hang on a second. Capra?

Yeah.

You call that a cheery movie, “It’s a Wonderful Life?”

Well, I think Capra was an optimist and I think there’s a . . . I think —

I think Nick’s an optimist. I think he’s more optimistic than . . . Nick sees the world as it is, but he still loved engaging with it. I think that you have to realize that a lot of Nick’s songs are incredibly funny.

Yeah. Sure. Same with Leonard Cohen. There’s a gallow’s humor, I would say.

Yeah. I wouldn’t call Leonard Cohen depressing. I think Leonard Cohen’s fucking, you know . . . That guy is like the . . . he’s the greatest songwriter that ever lived.

Yeah. Well, definitely near the top, yeah.

He’s depicting the human condition, which is . . . the human condition is ultimately tragic. I mean, you read biographies, right? Aren’t they all tragedies in way?

They pretty much all end in the same place, don’t they?

Yeah, so I guess I don’t see them as depressing. You know what I mean? I think that there’s beauty . . . I mean, there’s no beauty without truth.

Sure. Well, I do. Maybe I’m not making myself clear or maybe we don’t agree here. I mean, I spoke to Johnny Marr of the Smiths the other day, for instance, and he very much loves and prefers melancholy music. I’m the same way. Cohen, Smiths, Richard Thompson, Gillian Welch, old, sad blues songs. This is my pantheon.

In the States, at least — you come from a different culture — but in the States, we generally like our art happy. I mean, most Hollywood movies, the mainstream ones are cheery . . . the music that becomes popular. You know, and happy music is fine, too, but I am just saying, I wonder if you feel a special connection yourself, with tragic and sad stories. I certainly do. I don’t mean that as an insult.

You may say that the majority of movies are happy.

American movies.

American. No, OK. No, the American movie is pretty much dead as an art form, pretty close to dead. What’s really going on in America at the moment is television. Right?

Right.

Television has replaced movies as being where the real is being created. I don’t think that you’re seeing a lot of happy TV shows.

Well, that’s an interesting point. Certainly the good ones. I mean, I think of the shows that I watch. “The Americans,” “The Affair,” “Mad Man.” “Mad Man” had a fun side, but these are all deep shows with a lot of darkness . . . “Westworld.” The deep shows tend to be pretty grim and the smart shows are the dark ones. So yeah, you make a good point.

Yeah. I guess what I’m saying is, maybe there are people who prefer comic-book movies, but if we’re living in a society where the prevailing myth is that we’re teenagers who develop magical powers at the first sign of trouble, which is basically what the superhero movie is. It’s just ridiculous. It’s a kind of an opiate. . . . It’s a moronic kind of monkey-button opiate. . . . And you just elected Donald Trump.

Yeah, absolutely. No argument there. Those superhero movies make money because we have an infantilized or at least adolescent mainstream culture. You can see it at the ballot box as well.

Let me hit you with two more questions and I’ll let you go. Cave has been very interested in Christianity and I imagine mythology, too, but especially Christian imagery, Christian iconography, the Book of Revelation especially. He said at times that he is a Christian. Other times he said he is something like an atheist.

I wonder what you think his relationship is to those stories and those images — if perhaps he treats the Bible and the Christian motifs sort of the way most of us treat Greek and Roman and Norse mythology, as another body of resonant stories you don’t necessarily have to “believe” in.

Well, I’ll give you my personal take on it. I don’t speak for Nick.

Right, sure.

My theory is that junkies tend to divide the world into heaven and hell. And I think that Nick — he may never admit this — but I think that he’s essentially a spiritual person. I think he may not believe in a higher power or he may, but I think that he is a seeker of truth. I think that he is coming to a point in his life where he realizes that the only control that he has is in how he responds to things. He cannot control things, but he can control the way he deals with things.

Sure.

I think that that’s essentially a spiritual idea. I think, obviously, he’s a person who is cognizant that life is painful and beautiful. I think that you have to develop a way to deal with that and the only way to deal with that is essentially to deal with yourself. I think that anybody who is looking at art is not looking to have their minds changed or they’re not looking to have their lives changed. They’re looking to see a reflection of themselves in it, you know.

Right. Would you prefer that people, experiencing art, would try to change their lives? Is that what you as an artist would like to do?

No. I think that’s folly —

You think that reflection[-inducing art] is a more valid kind of art?

Yeah. I mean, I think that’s what it is. I think that’s what we do.

Yeah, I want to hit one last question. I’m just curious what’s next for you. I wonder what you’re hoping for in your next project or two?

Well, I’m trying to make a film about Marilyn Monroe, which I’ve been trying to make for years, but we’ll see if that happens or not.

You mentioned television also. I mean, so many indie-film directors and ambitious people who want to make character-based work for grown-ups are going into cable television. Is that the sort of thing that you’ve done or hope to do in the future?

No, I haven’t done it, but sure. I would love to.

Yeah.

What I really want to do is make a movie about Marilyn Monroe.

Shares