The opening passage in Zadie Smith’s brilliant new novel, "Swing Time," deals with two mysteries. First, the protagonist is wrestling with despair and distress from some public defeat and humiliation, unknown to the reader. Acting as an invitation, the assumption is that should the reader continue reading, eventually the details of whatever scandal has harmed her reputation will emerge. The second mystery is one of beauty, and forever insolvable. It is mystery of the power of art.

As Smith’s protagonist wanders the cold streets of London, distraught over her suddenly troublesome future, she seeks emotional asylum in a theater hosting a conversation with an Australian filmmaker. She is pleasantly surprised to find that the director and his interlocutor are in the middle of an exchange about one of her favorite childhood movies, “Swing Time” starring Fred Astaire. They select a scene of Astaire dancing with three silhouettes to exemplify their theories on the film. Suddenly, she is transported out of the terrestrial world of her problems, and elevated to a higher, more peaceful intellectual and emotional plane:

“I felt a wonderful lightness in my body, a ridiculous happiness, it seemed to come from nowhere. I’d lost my job, a certain version of my life, my privacy, yet all these things felt small and petty next to this joyful sense I had watching the dance, and following its precise rhythms in my own body. I felt I was losing track of my physical location, rising above my body, viewing my life from a very distant point, hovering over it.”

For many Americans, including me, one of the most immediate and intense feelings in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s electoral victory was loneliness. I felt lonely, even though I still had my wonderful wife, my loving family and generous friends, because I felt detached and isolated from half of my country. I felt detached and alienated from my country itself. The America that excites and inspires me is the multi-ethnic, multicultural America in continual expansion of liberty and opportunity to people previously excluded. Suddenly, that America felt distant, and certain assumptions about how Americans respect pluralism, and require probity from people in power, were no longer safe to make.

There is the risk of overstating the problems. When some people, including Robert DeNiro, compared Trump’s victory to the 9/11 attacks, it seemed crude, distasteful and disrespectful to the thousands of people whose friends and family died on the planes, in the Towers or at the Pentagon. Loneliness, however, is legitimate. There are people who feel disconnected from their own friends or family members over the election. It might seem extreme, but not in modern history has a presidential election appeared to act as a referendum on the very virtues essential to the maintenance of decent, civil society — racial equality, hospitality for immigrants, acceptance of religious minorities, equality for women. If comparably moderate Mitt Romney had defeated Barack Obama in 2012, liberals would have felt disappointed, but not devastated. Donald Trump is a new mutation of the radical right — hostile to diversity and democracy — and it is difficult to have communion with anyone who supports the mutant.

David Foster Wallace often said that part of the purpose of good literature is to make people feel “less lonely.” Politics unifies in only its best moments. More often, it divides people according to ideology and class interest — and that is fine. Calls for unity are typically naïve and hollow. Especially now, when the president has surrounded himself with medieval thinkers as he prepares to vandalize decades of social progress, it is much better to follow the wise words of Christopher Hitchens, who advised readers to “look for encouraging signs of polarization and division.” Art, as Wallace understood about literature, is what has the potential to unite — unite the lone individual to a larger sense of belonging in the world, unite different individuals to the universal human experience connected only by what Walt Whitman called the “invisible roots.”

It is for this reason, among others, that Honoré de Balzac brought political debates among friends to a close with the admonition, “Let’s talk about more important matters,” and then ask a question about poetry, music or theater.

The more important matters for me, since the election, are those that offer reminders of human potential, rather than spotlighting the human propensity for stupidity. Engagement with art is not disengagement from politics, but the demolition of cynicism. Art that gives hope is the most powerful weapon against apathy, as cynicism only produces paralysis.

The new record from Metallica takes its inspiration from the failures of the human spirit — the suicidal reaper resting within every heart. James Hetfield, lead singer and chief songwriter, has often used his own struggles with alcoholism and capacity for self-harm as bitter muses for his creativity. The title of the new record, “Hardwired to Self-Destruct,” confronts directly the ugly reality of human catastrophe — the countless disasters carried out on individuals in private and on communities in public. The title track begins the record, and with thunderous intensity and velocity, Metallica demonstrates that despite all of the seasonal jeering accompanying their more recent music, they are still the masters of metal. The first line of the chorus, given the record’s release a mere week after election day, makes one wonder if in addition to their musical genius, the members of Metallica also possesses psychic powers. “We’re so fucked!” Hetfield shouts in his characteristic growl.

Many people relegate heavy metal music to an expression of rage, but when done well, it is also the amplification of rebellion. As Albert Camus opined, every act of rebellion is both against and for something. Metallica’s music not only expresses rage against the darkness — the injustice, the masochistic aspects of human nature — but seeks to revolt against it with music that is loud, violent and aggressive. It channels rage into an artistic enterprise. Although Metallica deals mainly with matters of the heart, their example of controlling the chaotic whirlwind of feeling into creativity seems particularly relevant right now.

The timing of Metallica’s release, purely coincidental, took on larger meaning to those interested parties, just as Bruce Springsteen’s performance of “Thunder Road” at the election eve rally for Hillary Clinton, was, in hindsight, a tragic forecast of lost dreams. “Thunder Road” is a romantic anthem of triumph — a musically dynamic tribute to the faith in love’s capacity to conquer all enemies. “The Promise” seemed like a more resonant song the day after the election. Near the song’s conclusion, the narrator, perhaps the same pleading lover of “Thunder Road,” reminisces on years of disappointment and betrayal. What once held such promise now only signals heartbreak: “Thunder Road / Now, baby you were so right / Thunder Road / There’s something dying down on the highway tonight.”

Few songwriters capture the sweeping drama of betrayal better than Bruce Springsteen. His masterpiece, “Backstreets,” with its irresistible romance and guttural passion, is the finest example among many of his ability to melodize personal heartache. He has often claimed that his songs follow the format of “blues verses and gospel choruses.” The blues, as Ralph Ellison described them, are a “chronicle of pain expressed lyrically.” The gospel is the substance of faith giving one the means to escape that pain. On the same record as “Backstreets” is “Born to Run,” and many years later, with political and historical inspiration, Springsteen would write and record “The Rising,” “My City of Ruins” and “Long Walk Home.” The promise that still survives is the eventuality of a homecoming. Springsteen gives a soundtrack for the trek back to a world of joy and hope — a world still recognizable to those searchers on the highway moving toward that “place we really wanna go.”

The so-called “white working class” is now the subject of much attention in America. Few songwriters have depicted the lives of white people in rural America as brilliantly and complexly as John Mellencamp. With “Paper in Fire,” Mellencamp wrote a song about self-destruction following the death of his uncle, who was a bitter drunk and a member of the John Birch Society. Economic hardship does not justify hatred, and in the role of songwriter-as-reporter, Mellencamp “looked out his window” to discover that many people in small towns throughout Indiana were allowing their instincts of fear to overtake their faculties, creating bigotry and hatred in place of community and hospitality.

“Bigotry and hatred are enemies to us all,” Mellencamp sings in “Walk Tall,” one of the songs he says he wrote in an attempt to “make people feel good about themselves.” Another feel-good song also had death as its inspiration, the death of John Mellencamp’s grandfather. “Minutes to Memories,” one of the most lyrically beautiful rock songs in the American canon, tells the story of a man who “worked his whole in the steel mills,” “earned every dollar that passed through his hand,” claimed his family and friends as the “best things he’s known,” and rested comfortably at night because “an honest man’s pillow is his peace of mind.” The rollicking, 1960s style rock of the song, along with Mellencamp’s full-throated vocal delivery, gives powerful contrast to the poignancy of the lyrics and offers the reminder that in the small towns of Trump’s America, much like the town where I live, there are good souls.

If I could award one band the title of “best band in the world,” I would bestow that honor on Gov’t Mule. Led by musical typhoon Warren Haynes, Mule is a southern rock, blues and soul jam band. Haynes’ voice, larger than a mountain, accompanies his Hendrix-style guitar virtuosity to express everything all at once — anger, lust, love, and despair. Whether they are playing their own original compositions, ranging from hard rock to reggae, or covering anything from Ray Charles to Black Sabbath, Mule gives amplification to the absurdity of borders. Resistance and resilience against the wall builders will require the spiritual nourishment of art that defies borders and evades category. With every performance, Mule accomplishes that feat.

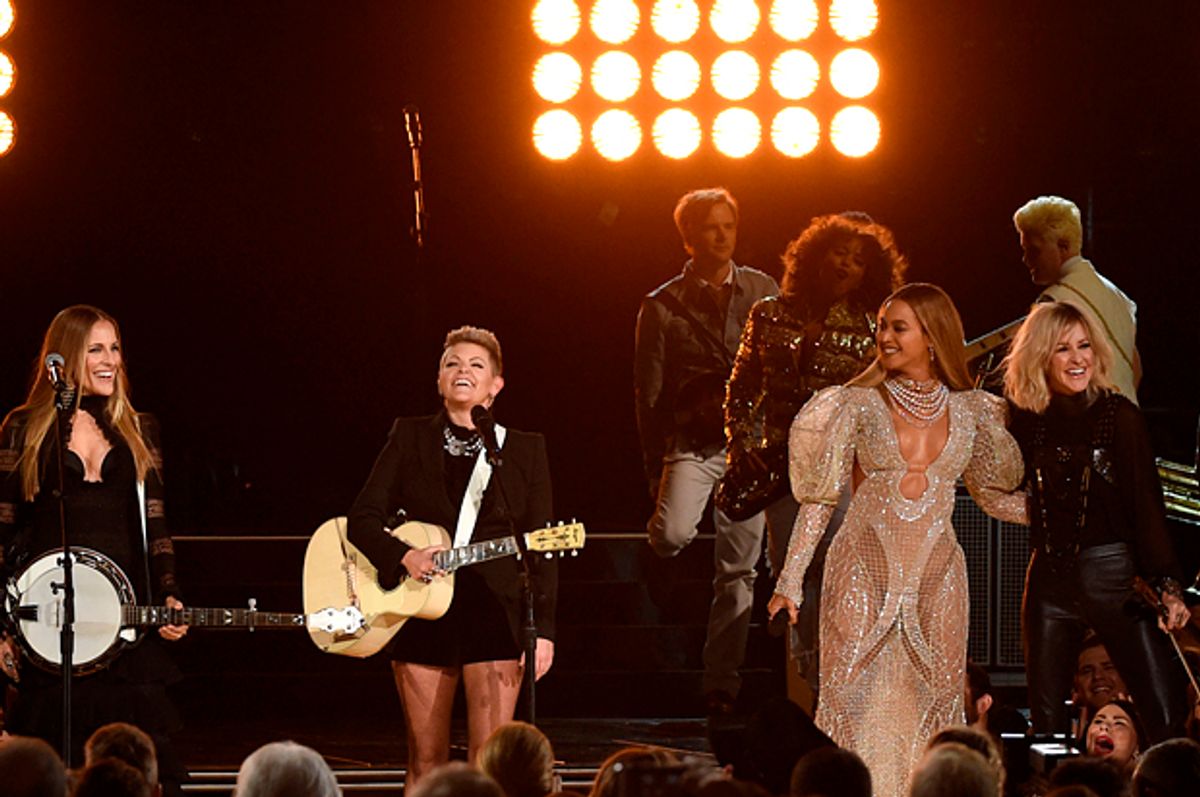

A particularly powerful performance in the wake of Trump’s election was the unexpected duet between the Dixie Chicks and Beyoncé at the CMA Awards. The usual suspects, always guilty of boring anyone within earshot, criticized the collaboration because Beyoncé is not a “country” singer. Petty classifications are useless. There is good, and there is bad. Beyoncé and The Dixie Chicks are good singers. They combined artistic force to offer exciting instruction in the close connection of American musical forms. Country and rhythm and blues emanate from the same region. Beyoncé and The Dixie Chicks singing a song that sounds equally hillbilly, urban, pop and traditional is the exact picture of America necessary to maintain under the assault of Trump. It is the America of enormous ambition — the America where icons like Nina Simone, Elvis Presley, Prince and Bob Dylan proved that the only limit on human synthesis and affection is the size of an artist’s imagination.

The embodiment and creation of community is easier in art than politics, but the art always acts as a target of aspiration. Even when it seems miles into a cloudy future, the artful citizen knows where to aim.

One of America’s most artful citizens, the late Kurt Vonnegut, offered wise words for the beleaguered: “No matter how corrupt, greedy, and heartless our government, our corporations, our media, and our religious institutions become, the music will still be wonderful.”

Shares