These days, many things can set off the swirl of a rage-and-grief dialectic. First a new story: A 17-year-old in California named Gurnoor Singh Nahal was shot dead on his street recently as he returned home from work. His grandmother found his body lying in the garage. She heard his call for hel before he died. He was supposed to graduate from high school this spring. The police have not yet identified a suspect or a motive, after many hours of searching the area and asking witnesses for help.

Or there is seeing a selfie, taken by Vice President-elect Mike Pence, of Donald Trump's presidential transition team, and combing dozens of faces looking for a face of color. Maybe you can see one black man, there in the back.

Or there is Sen. Jeff Sessions, a man thought to be too racist for the position of federal judge in the 1980s, who has been designated as Donald Trump’s attorney general. Sessions once allegedly joked that he thought the members of the Ku Klux Klan were “OK," until he learned that some of them smoked marijuana. As a 39-year-old United States attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, Sessions prosecuted three black civil rights advocates over what he perceived as voting fraud. The Senate subsequently rejected him for judgeship. He will now be at the head of the Justice Department.

Or there is the news that the University of Michigan issued a campus safety alert on Sunday after a Muslim student told police a white male demanded she remove her hijab or he would "set her on fire with a lighter." Police are still investigating. This is one of 437 incidents of harassment or intimidation reported between Nov. 9 and Nov. 14.

The rage comes first, or the grief does. In the middle of the night, it’s usually grief. In the face of complacency, it’s rage. Sometimes bewilderment sneaks in, under cover of darkness. Grief’s cousin, despair, is usually not far behind.

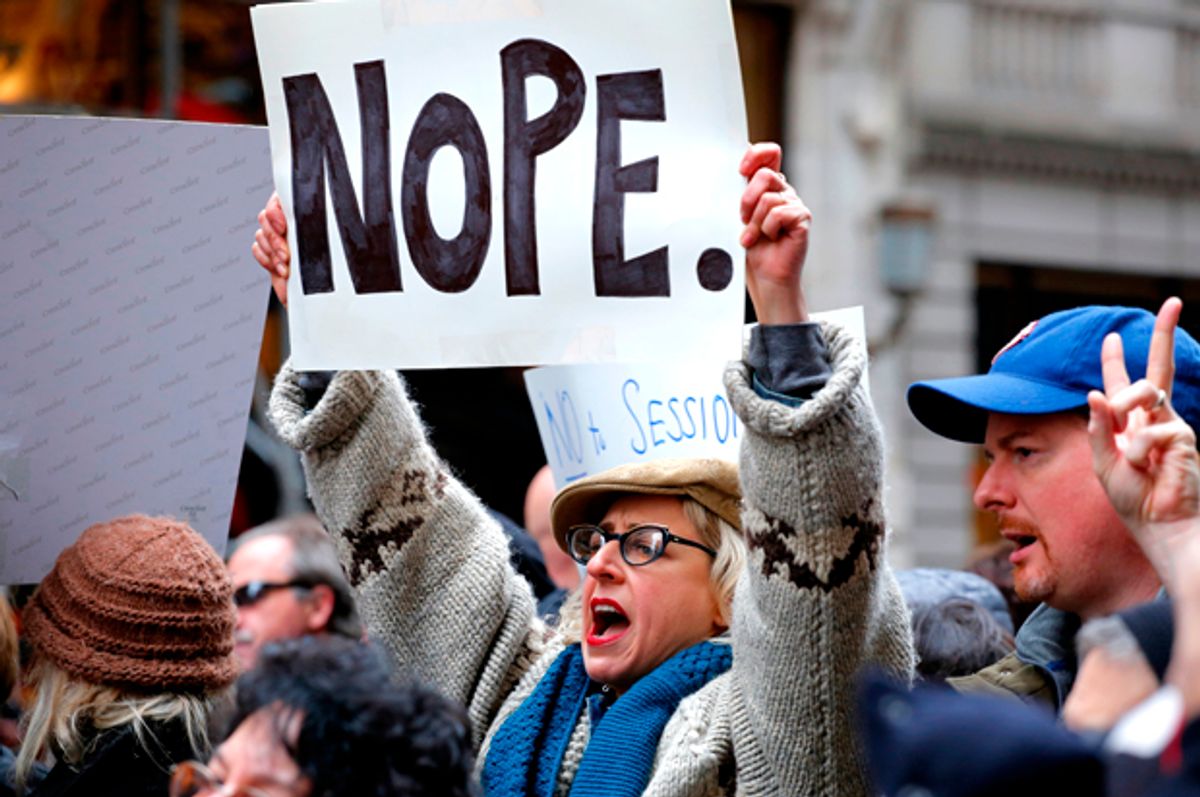

In response to public declarations of anger, on social media, in social settings I’ve noticed a trend. Some people become very uncomfortable in its presence. They argue with it, saying things like, “Well, he’s our president now, so let’s give him a chance.” Or “I don’t think he’ll actually do all the terrible things he’s said he will do.” They rationalize with the anger, others or even their own.

In a lecture entitled “Speaking of Rage and Grief,” given at Cooper Union in 2014, Judith Butler asks, “How often is sorrow effectively shouted down in rage? How does it happen that sorrow can bring about a collapse of rage?” She tells us that, “Mourning has to do with yielding to an unwanted transformation where neither the full shape nor the full import of that alteration can be known in advance.”

So we mourn, knowing some of what is to come; seeing it happening in the days since the election, seeing it happening all the time, really. It’s not as though racism, xenophobia, misogyny and the lot are new. And we don’t yet know the full shape of what a Trump administration, an America with apparent racists in the White House, in all levels of government. So we mourn.

Grief gives way to, or gives birth to, rage.

Renato Rosaldo is an anthropologist who spent 30 months living among the Ilongot community, 90 miles northeast of Manila in the Philippines. He sought to understand the Ilongot practice of head-hunting, severing a human head as a result of the rage that comes with bereavement. The headhunter says that rage is born of grief, and that severing a head allows him to sever his grief. The anthropologist remained confounded about this practice, until he himself encountered that very kind of anger found in bereavement.

Brittney Cooper, in her essay “In Defense of Black Rage,” makes the potency of rage clear, particularly in the face of historical dishonesty about what America is and how it was forged, particularly in the fact of political impotency. She writes, “Black people have every right to be angry as hell about being mistaken for predators when really we are prey. The idea that we would show no rage as we accrete body upon body – Eric Garner, John Crawford, Mike Brown (and those are just our summer season casualties) — is the height of delusion. It betrays a stunning lack of empathy, a stunning refusal of people to grant the fact of black humanity, and in granting our humanity, granting us the right to the full range of emotions that come with being human. Rage must be expressed. If not it will tear you up from the inside out or make you tear other people up.”

In her essay, “The Uses of Anger” poet and activist Audre Lorde examines the functions of anger. “Anger is loaded with information and energy,” she says, “My anger has meant pain to me, but it has also meant survival, and before I give it up I’m going to be sure that there is something at least as powerful to replace it on the road to clarity.”

Lorde has moved us from dialectic to trajectory. Perhaps our rage and our grief can be instruments of cartography.

Philosopher Maria Lugones, in her book "Peregrinajes/Pilgrimages," pushes us to map different kinds of anger, the kind of anger that vies for respect from an oppressor, or the kind that blames others for wrongdoing, or the anger of a person trying to resist oppression. She writes, “A beginning but significant step in the work of training our angers is understanding ourselves and each other in anger.”

So our work, if we listen to these theoreticians of social and emotional conditions, is not first to reconcile our grief and rage. It is not to try to rationalize them, to cover them with unconsidered action, to bury them as useless or distracting. As so many of our elected officials, and their compatriots, take their ill-defined “victory” as a mandate to increase state-sanctioned racism and sexism, our work is of course to resist with all the political and personal strategies we can muster.

One of those strategies is to become familiar with rage, born of grief or anything else. To understand it, to reckon with it, to become so intimate with it, such that we know when it aims to destroy us, and when it aims to destroy the institutions that oppress us. Therein lies all the difference.

Shares