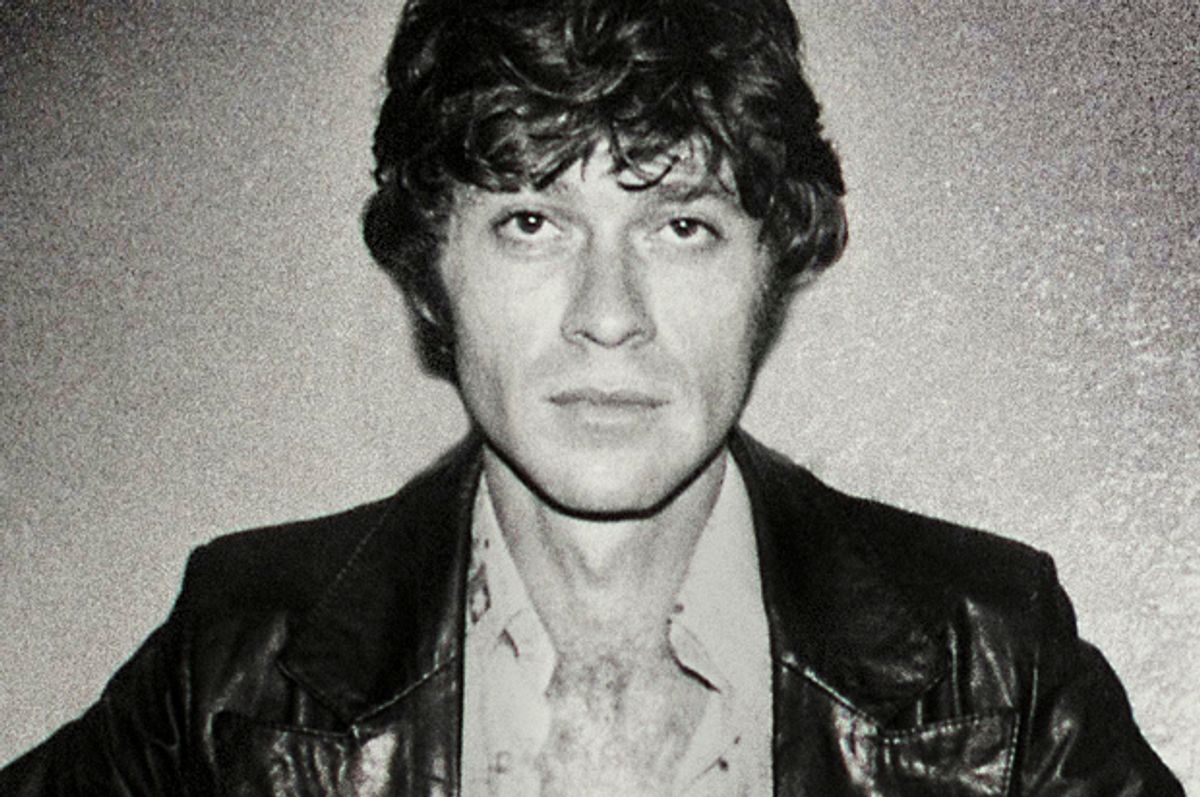

The Canadian musician Robbie Robertson is best known as the guitarist and main songwriter for the Band (originally called the Hawks), who recorded several classic albums and toured with Bob Dylan, including accompanying him on his controversial electric tour in 1966. The group also hosted the concert memorialized in Martin Scorsese’s film “The Last Waltz.”

Robertson, who has a new memoir called “Testimony,” spoke to Salon from San Francisco, where he was on a speaking tour. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

How does completing a book about your life compare to putting out an album, finishing a tour, working on a movie? What’s the sense of accomplishment like?

This is a whole other extent of depth. It’s one thing to write a tune; it goes by in four minutes or so; you try to get in there what you can. But in writing this book — and I very much wanted to, as I understand, a lot of biographies, autobiographies are written from the point of view of the age of the people writing them. “I remember back when” and “this happened, and that happened.”

I didn’t want to do that. I wrote this book when it was happening. I went into that world, with those innocent big eyes, and I didn’t know what was going to happen next. That’s the way that I wrote it; that was the truth of it for me.

Being able to accomplish that — and I do have some kind of memory chip that allows me to do it — but it took me on an odyssey that every day surprised me. And in some cases shocked me. And it made doing it one of the most exhilarating experiences of my life.

One of the things that comes across in the book and from “The Last Waltz” is that you are, hah, a pretty good storyteller. I wonder if you think there’s anything to what Lester Young said — that a solo is like telling a story.

Yeah, I do. I think that there’s an expressionism in telling stories, improvising, being in it. That’s what I recognize a difference in. I see a lot of people who are terrific at recalling things, but if I don’t feel that it’s happening at that moment — if it’s purely a reflection — it doesn’t push the same electricity in me. So I knew in writing this book that's what I needed to go after.

How did you learn to spin a tale? Family? Friends? Sitting around with other musicians over beers?

I was and am a big reader. And as I write in the book, I was presented with a gift of storytelling, by an elder on the Six Nations Indian reserve. He sent chills through me. He changed that life, in that moment. And I always felt like one of my chores in life was to grow up and hopefully be a real storyteller.

You spent a lot of time backstage before and after shows; you and whoever you’re touring with are just hanging out, drinking, bouncing anecdotes back and forth. . . . Did any of that hone your storytelling?

There wasn’t a lot of downtime. We were playing most of the time, seven nights a week.

Wow, in “The Last Waltz,” it seems like most of your time was spent playing pool and sitting around drinking moonshine backstage.

Not so much!

Well, almost every night of Dylan’s 1966 British tour was just released. This was a controversial but also incredible set of shows. I once paid an enormous amount of money for the Manchester concert [recording] back when it was a bootleg. What was it like to be there? Scary, exhilarating? You’re in your early 20s, people are shouting at you?

Yeah, I was, I dunno, maybe 21, 22. It was all of the above. It was frightening. It was exciting; it was challenging, it was hurtful. . . . It was . . . You just couldn’t wrap it all up in this pile — it was a musical revolution. You don’t know it when it’s happening. When it’s happening you think, “This is impossible. This cannot be happening! That everywhere, every place we play, they boo us and throw things and sometimes charge the stage with anger.” We are playing music that we have come to understand is real and it’s good and it’s revolutionary — and we are going to have to go bold on this, and stand up for this revolution.

And at the end of the game, now they’re releasing this music like it was the greatest thing ever. But while it was going on, believe you me, there were some people telling us we needed to make changes, and we didn’t budge.

Did you play guitar on “Blonde on Blonde”?

Yeah.

Oh man. I don’t have anything interesting to ask on that one. It’s just awesome.

Here’s one though: There’s an essay by Greil Marcus — the liner notes to a Richard Thompson collection — where he says that the '60s were not really about peace and love. There was always a sense that someone was lurking in the shadows, ready to pull the plug, shut it all down, to stop the show — that it could all end really badly. Did it feel scary and dangerous at times?

I don’t know who else was playing where people were screaming and booing and throwing shit at them. . . . I can speak to that!

But not just musically. I mean, by the end, Nixon was president. There was a backlash among the “silent majority.”

Were you aware of the other side of things?

Oh, yeah. Everybody got it. But what made people rise to the occasion, make a big noise and want to change the world. If nothing’s happening, nothing happens.

I really liked the music you assembled for “Shutter Island” [with pieces by Max Richter, György Ligeti and Lou Harrison]. How deeply are you into contemporary classical music? Do you go out to see this stuff live?

Oh, yeah! There’s wonderful depth in there — and people challenging what’s been done is always exciting. Sometimes it works; sometimes it doesn’t. The music I try to experiment with, whether I’m doing things in honor of American Indian artists or whatever, I like it when people try to reach outside the boundary. And do something that can have an influence in the interior.

So doing the music for “Shutter Island,” and the other Martin Scorsese films — it’s always a challenge, it’s always fun. And I hope that Marty and I keep doing this forever.

Did you work on the new one — his [Shusaku] Endo film [“Silence”]?

Yeah! Oh, it’s a trip.

Is most of the music Japanese, minimalist or what?

It’s more of a soundscape. Marty didn’t want it in any way a traditional score. So we were trying to find a place, almost like nature is breathing out an interior sound — where it becomes of the heartbeat of the characters.

You guys spent most of the '60s on the road, some of it with Dylan. . . . You went to [the bandmates' house] Big Pink and so on. Did you feel after those early Band records, as the '60s turned into the '70s, that something was seeping out of the band? That the chemistry was failing?

In the beginning — “Music from Big Pink” and “The Basement Tapes” and all of that — was such a wave of enlightenment, such a beautiful creative feeling. And then after “Music from Big Pink” — after all these years that the Hawks and the Band have been together — success comes along. And success can play tricks on you. We’ve seen it in all kinds of cases, in a million people. And we thought we were immune to that.

Everybody probably does!

Nobody is immune to it, you know? [That] is what we found out.

Shares