Six years ago, in 2010, an appellate court in Tennessee affirmed a family court ruling that had awarded Darryl Sawyer primary custody of his six-and-a-half-year-old son, Daniel. (All the names of family members involved in custody cases mentioned in this article have been changed to protect the children’s privacy.)

The court ruled in favor of Sawyer despite evidence presented by his ex-wife that alleged he had sexually abused their child. Three years earlier, Daniel returned from a visit with his father with suspicious bruises on his bottom. His mother, Karen Gill, immediately took the three-year-old boy to his pediatrician. “Your instant reaction is that you don’t want it to be what it appears to be,” Gill said, choking back tears at the memory. “You really hope there’s another reason for why he has these marks on him.”

But the doctor, Victoria Rundus, confirmed Gill’s worst fears. Dr. Rundus reported to the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services that she found reddish blue bruises on the child’s buttocks that could only occur from an adult “holding his buttocks forcibly open.” Gill thus began a long, arduous battle – that continues to this day – to protect her son.

Gill expected resistance from her ex-husband, but was surprised and shocked to find herself facing an even more formidable obstacle to her son’s safety in family court.

By the time the case was heard by a Tennessee family court judge in 2008, the state’s Department of Children’s Services had already investigated and had determined that Sawyer “‘was indicated’ as the perpetrator of sexual abuse of [their son],” according to court records.

Nevertheless, the family court judge granted primary custody to Sawyer, warning Gill that if she wanted unrestricted visiting rights with her son, she had better quit talking with the boy about the alleged abuse by his father. What’s more, she had to stop taking her son to doctors to be examined for signs of abuse.

Why did the court give the boy to his father despite credible evidence of abuse? It turns out the family court relied heavily on the recommendations of William Bernet, a psychiatrist and court-appointed custody evaluator. He convinced the family court to ignore the medical report, stating that Sawyer was not a pedophile or child molester and should be awarded custody of Daniel.

Other factors played into the court’s decision as well. Gill had earlier tried to restrict Sawyer’s access to the boy based on allegations that the court deemed unfounded. Gill’s suspicions were aroused, she said, because Sawyer had told her of a family history of incest. She feared Sawyer, in turn, would abuse his own children. Other allegations included comments by her ex-husband that “Satan speaks to him,” physical and verbal abuse toward her and threats of suicide. None of this, the court said, could she prove.

Dr. Bernet declined to comment on the case.

Daniel’s case is not unique.

In family courts throughout the country, evidence that one of the parents is sexually or physically abusing a child is routinely rejected. Instead, perpetrators of abuse are often entrusted with unsupervised visits or joint or sole custody of the children they abuse, putting children in danger of serious, often life-threatening harm, according to children’s advocates.

Our two-year investigation – which includes interviews with more than 30 parents and survivors in California, Ohio, North Carolina, New York, Georgia, Texas, Tennessee, Maryland and New Jersey – uncovered stories of children consigned to suffer years of abuse in fear and silence while the parents who sought to protect them were driven to the brink financially and psychologically. These parents have become increasingly stigmatized by a family court system that not only discounts evidence of abuse but accepts dubious theories used to undermine the protective parents’ credibility.

“Protective parents are asking the authorities to step in and protect their children and they’re not,” said Kathleen Russell, executive director of the California-based Center for Judicial Excellence (CJE), a watchdog group that focuses on family courts.

In scores of cases, the consequences have been lethal. News reports alone, while not comprehensive, paint a startling picture. From 2008 to 2016, 58 children were killed by custodial parents after family courts around the country ignored abuse allegations by the protective parent, according to an analysis of news reports conducted by CJE. In all but six cases, protective parents were mothers who had warned family courts that their children were in danger from abusive fathers who later killed them.

“The authorities are blaming the protective parents and pathologizing them, and their kids are ending up dead,” said Russell.

How do family courts get away with these kinds of decisions?

“You can take the same amount of evidence to criminal court and a jury will convict beyond a reasonable doubt,” said attorney Richard Ducote, who represents protective parents trying to regain custody of their children. “And the appellate court will uphold the conviction and the sentence.”

But family courts have a different focus, explained Ducote, who also worked as a special assistant district attorney statewide in Louisiana prosecuting termination of parental rights cases. In theory they are supposed to consider first the best interest of the child. But in practice, Ducote said, “They’re concerned with the reduction of conflict [within the family] and getting along, which is good unless there is someone you need to protect the child from.”

Court records are often sealed, a practice intended to protect the privacy of children. As this investigation shows, however, it’s a practice that can put children in greater danger by blocking outside oversight.

Moreover, the high cost of litigation throws up a formidable obstacle for most parents fighting to get their children out of harm’s way. There is little research on court costs, but a preliminary analysis of a national survey of 399 protective parents by Geraldine Stahly, emeritus professor of psychology at California State University, San Bernardino, showed that, for some 27 percent of these parents who ultimately declared bankruptcy, the costs were about $100,000.

No government agency tracks the number of children nationally that family courts turn over to their abusers, and existing academic research is largely regional. Advocates have tried to put a number on it by culling statistics from primary and academic sources. They estimate that at least 58,000 children a year end up in unsupervised visits with or in the custody of an abusive parent. A 2013 analysis in the Journal of Family Psychology cited studies that show that anywhere between 10 and 39 percent of abusers are awarded primary or shared custody of their children.

However difficult it may be to quantify, high-level government officials recognize the breadth of systemic failure. “It’s a terrible situation,” said Lynn Rosenthal, who served as the White House Advisor on Violence Against Women from 2009 to 2015. Before going to the White House, Rosenthal personally saw the extent of the problem while working with many state coalitions on child welfare and domestic violence. “We saw this all over the country,” she said.

How do abusers get custody? A big part of the answer lies in the very experts that courts turn to for help in evaluating the fitness and safety of parents.

In sounding the alarm over her suspected abuse by her ex-husband, Gill ran squarely into an unexpected obstacle. Bernet and his colleague, James Walker, stated in a joint report that they used a battery of tests to evaluate Sawyer. They claimed that Sawyer tested as “low risk” for sexual offenses and was not a pedophile. These tests included a sex offender risk test known as the Static-99, the Minnesota Sex Offender Screening Tool, the Sex Offender Risk Scale and the Abel Exam for Sexual Interest.

But according to Anna Salter, PhD, who has conducted research with sex offenders for two decades, using such tests in family court is meaningless. “They can’t be used to determine if someone is a child molester,” explained Salter, who is the author of “Predators: Pedophiles, Rapists and Other Sex Offenders” and a consultant with the Wisconsin Department of Corrections. Instead, she said, the tests were intended to evaluate people already convicted of child molesting to determine the likelihood of recidivism. The Abel exam, which tests for sexual interest in children, does not yield meaningful results, she said. “It is based on how long you look at the pictures of the children. There are now sites that tell you how to fake it – ‘just look away.’”

Beyond the tests, Bernet also wrote that Gill, not Sawyer, was causing harm to their son. “Since 2003, [Gill] possessed personality traits of parents who make false allegations of sexual abuse,” such as “strongly criticizing” Sawyer. Bernet also ascribed “narcissistic tendencies” to Gill, stating that she “appears to lack insight into the strong feelings and motivations that are driving her current behavior in casting [Sawyer] as a child abuser.”

Among his primary concerns, wrote Bernet, was that if Gill were allowed to continue questioning her son about his father’s actions, she would “induce [Daniel] to share her false beliefs.”

Bernet dismissed Daniel’s claim that his father had “put a stick in my butt,” writing that the child was, rather, making up a fantastical story under prompting by his mother. Similarly, he contended that an interview with Child Protective Services did not show Daniel was “capable of giving a simple, coherent description of a past event.” Of the bruises on the child’s buttocks, Bernet noted that Sawyer said he thought they were from water slides at the two water parks that he and Daniel had visited two days in a row. His acceptance of Sawyer’s explanation at face value appeared to ignore a physician’s description in court records of bruises “shaped like thumbprints” that were “inside [Daniel’s] buttocks.”

Child advocates say they regularly hear of custody battles similar to the Sawyer-Gill case in which an evaluator deflects the court's focus on potential abuse by alleging that one parent is brainwashing the children to believe that they are being abused. This behavior is known as Parental Alienation Syndrome (PAS) by those who embrace it and deemed questionable science by organizations such as the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges and the American Psychological Association.

As far back as 1996, a Presidential Task Force found a “lack of data to support” the diagnosis of Parental Alienation Syndrome. Citing this report, the American Psychological Association in 2008 declined to take a position on the “purported syndrome.”

Bernet, however, is among a faction of family court professionals trying to get PAS accepted as a recognized disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the bible of mental health practitioners. So far, he and other advocates of PAS have not prevailed. Bernet said in an interview that “the actual words are not in the DSM-V [the latest revised version], but the concept is,” pointing to what he describes as three new diagnoses that each have features of PAS.

Dr. Darrel Regier, vice chair of the DSM-V task force, said that the DSM acknowledges that alienation can figure into relationship dynamics. But “we were very careful not to include in there a diagnosis of PAS,” he said, adding that “the international community isn’t buying PAS as a diagnosis either.” With respect to how it’s used in family court to discredit abuse, he said, “If there’s evidence of abuse, then that’s what should drive the courts.”

The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges cautions jurists in custody cases “not to accept testimony regarding parental alienation syndrome or PAS,” according to the guidebook Child Safety in Custody Evaluations. It adds, “The theory positing the existence of PAS has been discredited by the scientific community.”

Many courts, however, have paid little attention to these recommendations. “There’s this myth out there that there’s over reporting of abuse when in fact, statistically, there’s an underreporting of abuse,” said retired Kentucky Judge Jerry Bowles, a co-author of the guidebook.

Judge Bowles, who trains his fellow jurists in domestic and family violence matters, said that it’s common for courts to believe that mothers press for no contact with their ex-spouses for reasons other than safety. He ties this misconception to lack of training and understanding among jurists about violence in families.

A pilot study by Joan Meier, a professor of clinical law at George Washington University Law School, supports Bowles’ observations. In analyzing 240 published rulings in an electronic search for cases involving custody and alienation, she found that more often than not, accusations of abuse did not block access to children in family court settings. In some 36 cases where a mother accused the father of abusing their children, the court nevertheless ruled in the father’s favor 69 percent of the time. The tendency to discount the mother’s accusation was even more pronounced where sexual abuse was alleged: In the 32 such cases Meier identified, the father prevailed 81 percent of the time. She is now working on an expanded study examining the same issues – including intimate partner violence – in some 5,000 cases with a grant from the National Institute of Justice.

Bernet’s characterizations of Sawyer as the good guy and Gill as mentally disturbed are consistent with a troubling pattern that organizations fighting to reform the family courts see in these cases. They include the Center for Judicial Excellence, the Domestic Violence Legal Empowerment and Appeals Project and The Leadership Council on Child Abuse and Interpersonal Violence.

"The research shows that the family courts are a perfect place for abusers to get custody," said former White House advisor Rosenthal. “They can manipulate the evaluator; they can manipulate the [court- appointed] guardian; they can manipulate the judge. They make themselves look good and they make her [the mother] look crazy.”

Cynthia Cheatham, a Nashville-based attorney who represented Gill in her appeals case and whose practice involves helping protective parents fight to regain custody, agreed.

“They have Mom, who looks like she just stuck her finger in a light socket, and the perpetrator, who may have stuck his finger in his kid’s vagina, who looks like a very normal guy.”

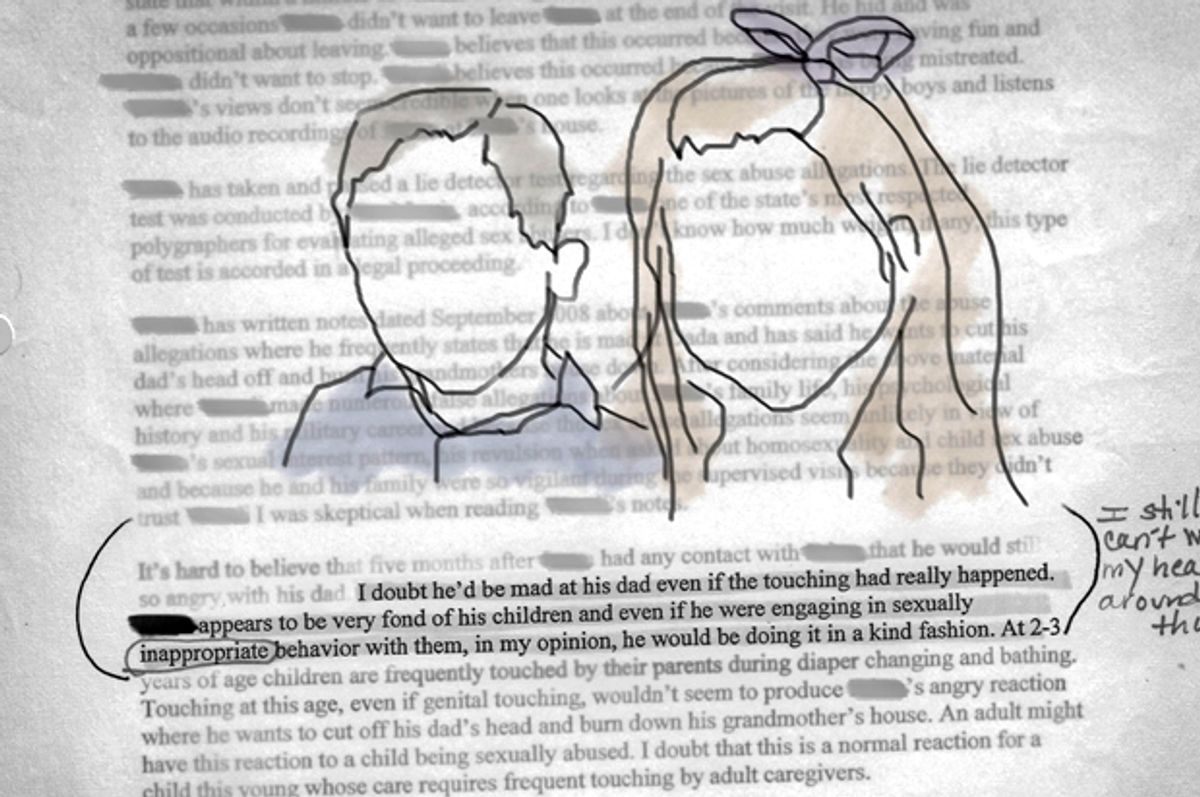

Some custody evaluators appear to go to great lengths in their effort to normalize perpetrators’ behaviors. Thomas Hanaway, PhD, also in Tennessee, wrote that a father who had already been substantiated as a perpetrator of sexual abuse by the state’s child protective services “appears to be very fond of his children and even if he were engaging in sexually inappropriate behavior with them, in my opinion, he would be doing it in a kind fashion.” (Emphasis added.) Hanaway did not respond to requests for interviews.

Alina Feldman, 16, of Dallas, Texas, wishes that disclosures of abuse she first made when she was four years old had been taken seriously by the court’s therapist and custody evaluator. Had they done so, it might have spared Alina what she describes as years of severe abuse and misery in her father’s care while separated from the mother she loved.

“He would hold a knife up to my neck and threaten to kill me,” Alina recalled. “He would take a knife and cut my arm. Sometimes he would choke me until I passed out. He would snap my wrists.”

Instead of taking her to a doctor, she said, her father would put her wrist in a brace until it healed. He would also twist her arms in different directions, she said. As she began puberty, he would sit on the toilet seat and watch her while she showered, she said. If she cried about missing her mother, she said, he punished her by withholding food.

Her father also kept Alina isolated, she said, adding, “If he checked the mail, I came with him every time. I was never alone. I didn’t know my address. I wasn’t allowed to know it.” Alina said she tried killing herself several times. “I’d take a bunch of pills, but I always woke up.”

Rachel Feldman, Alina’s mother, had asked the family court years earlier to modify the joint custody arrangements she had with her ex-husband, Jack. Four-year-old Alina had come home from a visit with him in January 2005 and described how her father had spread his “butt cheeks,” inviting her to smell.

Records detailing visits between Alina and the court-appointed therapist, Gail Inman, showed that the child said that her “father puts her hand on his penis” and that “his privates feel squishy.”

Inman, however, testified in court that she didn’t report the disclosures to authorities because it wasn’t clear if the incidents were “purposeful or accidental” and seemed to have happened “a long time ago.”

Rachel Feldman filed a complaint against Inman for not reporting the disclosures.

Later, the Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors sent Inman a letter advising her to comply with the statute that requires reporting of disclosures of abuse by a minor. Inman did not respond to emailed requests for an interview.

The custody evaluator in the case, John Zervopolous, told the court that living with her father was “a much better fit for [Alina ] in terms of parenting situation.” His reasoning? The father was better able than the mother to control the child during their office visits with him.

During his one scheduled visit to observe the mother’s interaction with her daughter, Zervopolous said the child resisted going into his office and also ran down the hall as her mother tried to coax her to come back, according to court records. Zervopolous acknowledged that he might have upset the child by asking her about the sexual abuse allegations in a meeting alone with her immediately before the family meeting. That the child was meeting alone with him prior to all of them meeting together was apparently unexpected, the result of a misunderstanding, and he said it also could have led to the child’s behavior.

But whatever occurred on that visit, Zervopolous saw it as a problem with Rachel Feldman’s parenting. He criticized her for allowing Alina to express anger and for giving her choices when she was acting up “instead of commanding her to do something.”

Zervopolous told the court that Jack Feldman’s psychological test scores “were within normal range.” In contrast, he described Rachel Feldman’s scores as indicative of people “who are immature…lack insight into behavior, have simplistic answers to problems and are often in conflict with others.”

Zervopolous wrote in an email response to a request for an interview that, “It is improper at best for me to comment on any case in which I have been professionally involved. Further, I don’t wish to discuss any other family court issues.”

In 2006 Judge Susan Rankin awarded custody to Alina Feldman’s father. In her ruling, Rankin said that Alina’s mother would “endanger the physical or emotional welfare of the child if she spent time with her.” Rankin said that Rachel Feldman “has no insight into how her behavior impacts her child…coaches the child to say certain things … alienates the child from the father … creates the problems in her child that she complains of ….” Rankin also barred the mother from coming within 1,000 feet of her daughter. If she wanted supervised visits with her daughter, the judge wrote, she first had to post $50,000 cash bond. Why such harsh terms? The judge deemed Rachel Feldman a flight risk “due to her emotional instability and belief that the father is harming the child.”

Then, in April 2012, Alina reported to a teacher that her father had pinned her down on his bed the night before and that she fought him off, escaping to her room and locking it. “I thought, either way I am going to succeed in killing myself. If I tell, he’s going to kill me. If I don’t tell, he’s going to kill me. I cannot take it anymore,” Alina recounted.

An affidavit to the court by her then court-appointed therapist, Donna Milburn, confirmed the disclosure. Alina described how her father insisted “she was going to sleep in his bed that night” and how frightened she was. Within a month of her disclosure at school, followed by her therapist’s report to the authorities, Rachel Feldman petitioned the court to get sole custody of her daughter. Eleven days later, Alina’s father signed an agreement to terminate his parental rights.

Alina says she’s relieved to be living again with her mother, although she continues to suffer anxiety and depression. "I definitely get scared sometimes because I think I see him."

Joyanna Silberg, PhD, a senior consultant for child and adolescent trauma at Sheppard Pratt Health System in Baltimore, has identified 55 similar cases where courts granted custody to alleged abusers, and where the children were taken back to safety after another intervention.

While some of those children are managing, she said, “all of them have severe mental health wounds that last a lifetime – the lifetime knowledge of the betrayal of the system against them, of people who are supposed to help them [who] actually harmed them, that their word was not accepted as true.” These children also suffer from the knowledge “that the person they loved most in the world, often the mother, was disempowered to do anything to protect them,” said Silberg, whose research was financed by the Department of Justice. Then there’s the “repetitive knowledge of the actual abuse they suffered and the harm to their bodies and souls for that.”

Parental alienation syndrome also made its way into a Cleveland, Ohio, custody case involving physical abuse. Family court Judge Judith Nicely awarded Leonard Doyle custody of his two children in 2012. In her order, Judge Nicely quoted from a custody evaluator’s report that the “mother was found to have demonstrated a pattern of efforts to alienate the children from their father, to remove father from their lives, and to convince the children that only she has their interest and safety at heart.”

Shortly after the court’s decision, Doyle’s 11-year-old son and his younger sister barricaded themselves inside their grandparents’ house and called 911. Each held a knife to their own neck.

“If you make me go with my Dad,” said the boy into the phone, according to a 911 transcript of the call, “I’m going to kill myself.” The teen and his sister had just been told by their mother that their father – who had physically hurt them, causing injuries requiring emergency medical care – had been awarded custody of them and control of whether or not they could visit their mother.

Doyle was a man already known within the court system to be violent, to download child pornography and to have served time in prison for obscenity. A 2008 sentencing memo by the U.S. Attorney’s office against Doyle said that an investigation of his computers by the FBI found that he had been downloading “numerous stories glorifying and salaciously describing sex between adults and children.” What made the material especially disturbing to the U.S. Attorney’s office, according to the memo, was “the fact that he was the custodial parent of small children at the time,” a serious concern that, the prosecutor wrote, “mandates a five-year term of imprisonment.”

The sentencing memo noted numerous encounters between Doyle and police, including a disorderly conduct conviction in 2003 for an incident in which he dragged “a bleeding victim by his feet on the streets.” In 2008, he was sentenced to 13 months in prison.

Leonard Doyle declined to address questions publicly for this story, but rather threatened in a text message to file a lawsuit should “one false statement or misleading implication” appear regarding his case.

In late September 2008, not long before Doyle began serving time, his son called his mother, begging her to pick them up. According to court records, the boy said that his father had chased him over the lawn with his car. Frightened for their safety, Robin Doyle said that she picked up the children and took them to a domestic violence shelter, where they received counseling.

A doctor who had diagnosed the son with a mild concussion in another incident in 2010 testified in the 2012 custody case that she believed the boy when he told her that his father had hit him in the head. The incident had also generated an investigation that similarly determined that abuse was “indicated,” according to a letter by the Geauga County Board of Commissioners in March 2010.

The juvenile and family court judge’s guidebook cautions courts weighing custody decisions that “any allegations of abuse, whether made by the at-risk parent or the child, should be taken seriously.” But Judge Nicely discounted the child’s allegations despite a doctor’s confirmation that he was injured. She relied instead on testimony of the court-appointed supervisor for the visit, who said she had not seen Doyle strike his son and did not think the incident occurred.

Despite the abuse report, the judge wrote that the father had been “extremely patient during these proceedings,” and that he had “appeared to have matured.” In contrast, she said, the “Mother has done nothing to encourage the children to have a positive relationship with Father after his incarceration and has actively sought to keep Father out of their lives.”

Regarding abuse of the children, the judge relied on a report by the guardian ad litem, Sandra McPherson. In her report, McPherson explicitly stated that she “works with the premise that domestic violence by [sic] Father against the children did not happen.”

As is common, the court has sealed all of the medical and psychological records relating to the children.

Robin Doyle has not seen her children since October 2015, when she saw them over a two-week period, when the local “hospital did not want the children to be in their father’s custody,” said Doyle. At the time, her ex-husband had allegedly pushed their son, then 14, so hard that the boy’s hand went through a window, requiring emergency surgery, the children told police in statements obtained through public records requests to the local police.

Several months later, the children ran away from home, escaping to the nearby woods with just snacks in their pockets. Picked up by police, the children were questioned and read their rights. In a statement to police, the daughter talked about the injuries to her brother, and wept that they were terrified of their father, and afraid to go home.

Robin Doyle filed a protective order on behalf of her children. Unbeknownst to her at the time, her ex-husband had filed a similar order against her. After two weeks, the children were back with their father.

“They won’t take these children’s pleas for help seriously,” said Robin Doyle, talking about the court. “They just ignore it.”

Joan Meier, who is also the legal director of the Domestic Violence Legal Empowerment and Appeals Project, and provided an amicus brief for the Doyle case, ties the court’s actions to parental alienation.

“Once you’re labeled an alienator, you’re wearing a scarlet A and they will not even consider giving the children back to you even when it becomes obvious that the children are being harmed in the other parent’s care, which is what you reported in the first place.”

In a recent interview, Doyle said that she prays daily for her children’s safety. “I love my children more than life itself,” she told a reporter. “I miss them terribly.” She reflects on the comments of one attorney who said one day, she’ll be able to let them see all of the years of court pleadings “and show them that I never gave up.” Doyle is trying to figure out her next move.

The outrage these family court decisions raise among children’s advocates is palpable. “You have an entire branch of government that is completely unaccountable to the public it serves,” said CJE’s Kathleen Russell. “You can’t prosecute mediators, custody evaluators, judges, so these people operate above the law, and until there’s accountability for these crimes against children, we’re going to continue to see this happening.”

One solution is to get Congress to take action on reforming the nation’s beleaguered family court system. A number of advocacy groups fighting child abuse and domestic violence, including Russell’s, have made some inroads.

A resolution asking Congress to recognize that “child safety is the first priority in custody and visitation adjudications” has been introduced by Republican Congressman Ted Poe of Texas and Democratic Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney of New York. The resolution asks Congress to recognize that more than 15 million children annually are exposed to domestic violence and/or child abuse; that child sexual abuse is “significantly under-documented and under-addressed in the legal system”; that research confirms that allegations of physical and sexual abuse of children “are often discounted” when raised in custody battles, and that “scientifically unsound theories like Parental Alienation Syndrome” are frequently used to discredit reports of abuse.

Meanwhile, back in Tennessee, Karen Gill and her son, Daniel, are hoping for justice. The boy is back with his mother, and their case against Darryl Sawyer is now pending in criminal court.

Gill, a tall woman with a broad smile and dark circles under her eyes, remembers the years when she only saw Daniel on visits. He was different, more withdrawn than the happy little boy she had known. She was afraid to bring up her worries again for fear of losing contact with him entirely. But in 2011 – three years after Gill lost primary custody of her son – Daniel, by then eight years old, broke down on a visit with her and told her his father was sexually abusing him.

Wary of returning to family court, Gill contacted the FBI. An investigation, including forensic interviews with Daniel, led to a grand jury indictment of Sawyer on four counts of child rape and one count of sexual assault.

According to the FBI’s report, Daniel said that Sawyer raped him on Saturday afternoons in the master bedroom and also forced him to watch “sex shows” on a laptop computer in the basement as he was being abused.

The report also stated that Sawyer, a veterinarian, put Daniel in a “dog cage” and shocked him with an instrument “because he had talked to his mother.”

A hearing in criminal court has been postponed several times for a variety of scheduling conflicts. Each failed court date, said Gill, has intensified an already oppressive anxiety in her. As long as Sawyer is free and not held accountable, she said, she will always feel vulnerable. "I feel hunted, like we're prey."

Asked to comment on behalf of his client, Sawyer’s criminal defense attorney, Ed Yarbrough, said “We’re not going to try this case in the newsroom. We’re going to try it in the courtroom.”

As for thirteen-year-old Daniel, he has waited four years to testify against his father. He’s hoping that if and when he gets his chance, this time he’ll be believed.

This story was produced in partnership with the G.W. Williams Center for Independent Journalism and supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Shares