Christmas music can be treacly, overfamiliar, corny and awful. But the few exceptions out there can be genuinely exciting — music you hear for only a few weeks each year, but often have a 20- or 30-year relationship with. For a lot of people, Vince Guaraldi’s "A Charlie Brown Christmas" record is a great memory that re-emerges every winter. The classic Christmas songs — many of them written by Jewish men in ties — like Irving Berlin's "White Christmas" have hardly become dated. More recent recordings by Sufjan Stevens and She & Him bring an earnest Christian spirit, and a sweet retro irony, respectively, to the table. There are also wonderful R&B takes on the winter solstice, like James Brown's "Santa's Got a Brand New Bag" and collections like "Soul Christmas," with Otis Redding singing "Merry Christmas, Baby" and Carla Thomas crooning "All I Want for Christmas Is You."

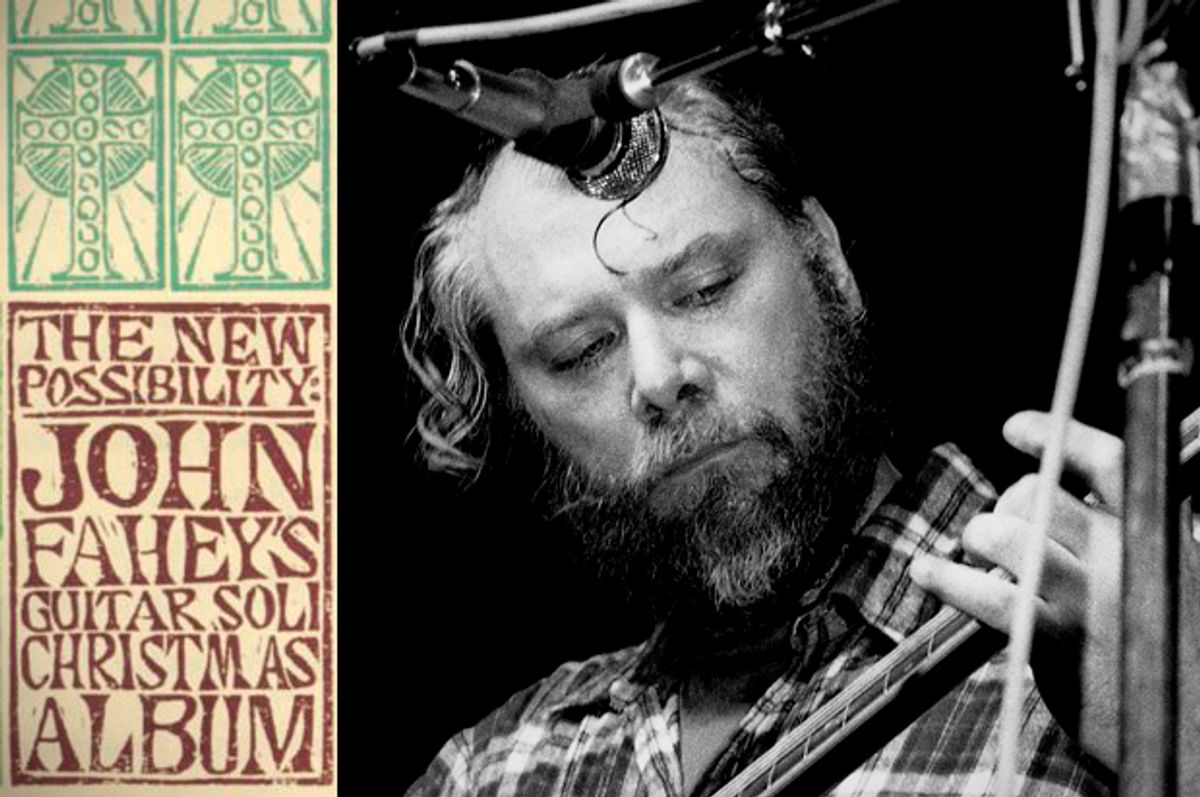

As delightful as all of these, but also mysterious and genuinely weird, is "The New Possibility," a close-mic’ed solo-acoustic record by the self-proclaimed American Primitive guitarist John Fahey. On the surface, this is a traditional collection of both classic Christmas songs (“Joy to the World,” “The First Noel”) with older, eerier pieces like “What Child Is This” (the music for which comes from "Greensleeves," which dates back to the 1580s, when Shakespeare was a teenager.) But listening to this album is not like going to church: It’s full of drones and weird tunings and spooky broken chords and clanging, angular guitar playing. It’s the songs you know all too well, but played by an avant-garde madman with an oddly appealing sense of melody. This is strange stuff, but you can hum a lot of it.

Fahey was born in 1939. Like Bob Dylan, who arrived two years later, he was part of the movement by American white kids to track down blues legends. Fahey managed to locate, for example, the great blues guitarist Bukka White. Fahey and friends also found an aged and forgotten Skip James in a Mississippi hospital, which helped spark the decade’s blues revival. In 1963, he moved from the Washington, D.C., area, where he’d grown up, to Berkeley and then Los Angeles.

Besides the Christmas record, Fahey recorded music inspired by acoustic country blues — his work in folklore at UCLA was on the Delta guitarist Charley Patton — as well as explicitly religious pieces like the Anglican hymn “In Christ There Is No East or West.” He drew musical inspiration from Bela Bartok and Charles Ives, but rarely played classical music on guitar.

“The New Possibility” brings together tunefulness and abstraction, black and white tradition. It’s no surprise that his cult enlisted indie rockers like M. Ward, Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth, and various Pacific Northwestern musicians after he settled in Oregon in his last years. His guitar style sounded fresh to these young ears. “The open strings are so dissonant with what he’s playing,” says Robert Fink, a musicology professor at UCLA, amateur acoustic guitarist, and self-described Fahey freak. It sounds like the blues, Fink said, but more so. “He just found other blue notes — and he would dwell on them for what felt like an hour.”

The Christmas album was released in 1968, and caught the guitarist before he'd completely spun out. “Because he was a ’60s guy, and had probably done a lot of drugs, there’s a stoned-out feel to it,” Fink said. You can have your middle-American cake, then and get high to it, too.

Fahey was a serious drinker, and known to many as an unpleasant fellow. One musician who I figured would be eager to rave about Fahey’s guitar playing refused to discuss him, calling him “a pig of a human being.” He spent his last years in Salem, Oregon — some of that time in a motel, some of it living out of his car — selling vinyl to used record stores and over the Internet. After a series of health problems, he died in 2001 after a coronary bypass operation. “His life was a dead end,” Fink says. “A classic tortured soul. He left behind wreckage.”

Fahey also left behind some bizarre and enduring music, and “The New Possibility” is close to the best of it. By a coincidence I don’t entirely understand, my father and stepmother had a (vinyl) copy of the album, and we played it so much at Christmas each year that I now feel like I know every note. I heard it way before I heard the modernist folk songs of Bartok, before I heard Sonic Youth’s alternate tunings, before I heard the unholy beauty of Richard Thompson’s guitar playing. I don’t know that any of these artists — some of my very favorites — would have made any sense to me if I had not heard John Fahey’s “A New Possibility” first, and learned to appreciate its dark magic. This eccentric, nasty man playing drones and holiday cheer on a steel-string guitar opened up my mind and ears, and helped me see God in a dissonant universe. Now please pass the eggnog.

Shares