Yesterday I heard through my cousin that the house I grew up in was being sold. “Owned by the same family since it was built,” said the real estate listing. It was a small, generic, two-bedroom tract home, originally with an unfinished second story, in Columbus, Ohio. My uncle had owned it for close to 40 years. Before him, my father had owned it for 20.

I am an engineer with a wife and two daughters, and all the juggling that entails, so I hadn’t thought about the house in a while. Now the impending sale took me back to my childhood. My sisters, my brother and I were born in the United States and English is our native language. Our father was born in Canton, now Guangzhou, and speaks Taishan and fluent English. Our mother is from Hong Kong and speaks Cantonese, Taishan and, after all these years in the United States, English with an accent.

Until recently I never considered us to be an immigrant family, although we certainly were. While growing up, the only other Chinese families I knew were relatives in neighboring suburbs. At the time, because the other kids largely accepted me, I was only dimly aware of being ethnically different. But now grade school memories surface: one boy calling me a “Jew” from across the street (in retrospect, probably the only epithet he knew); another, while playing flag football, blocking me with a fist to my stomach; yet another, tricking me into grabbing the end of a baseball bat smeared with excrement. Maybe it was normal bullying; however, I doubt it.

In the late ’60s, when I was 10, my family relocated from Ohio to California, leaving the house in the care of Uncle Toy, who moved his family into it and bought it some years later. Before we moved, however, I had one of the two bedrooms on the second floor. Uncle Toy’s son, who lived with us while he attended college, had the other one.

Every weekend for two or three years, my father had disappeared upstairs to build those bedrooms and a bathroom on the second floor. He learned carpentry and plumbing from reading “How to” books. He hauled planks of plywood by himself, and then filled the house with the whine of the circular saw and the smell of sawdust. When he came down to the kitchen for lunch, the handkerchief tied around his face made him look like the desperado in a cowboy movie.

As the second floor neared completion, we became excited about doubling the living space of our house and pitched in to help, screwing handles on drawers and doors, varnishing shelves and laying down linoleum tile.

That was a long time ago, and the house has since become a source of memories. My father leaving for work every day with an apple and an American cheese sandwich — one slice of American cheese between two slices of Wonder Bread. My mother discovering Spam. The bottle of whiskey with a piece of ginseng in the bottom. Making tofu, my parents squeezing soybean curds through a cheesecloth screen. Picking slugs out of the watercress we gathered from the Olentangy River. Relatives coming to visit on summer nights. My mother and aunts playing mahjong in the basement, gossiping in Chinese to the rapid clack-clack-clack as they shuffled tiles beneath an incandescent light.

From the time before grade school, I remember the milkman delivering milk in glass bottles, a photographer walking around the neighborhood with a pony, a neighborhood so newly developed that the trees were saplings and the yards didn’t have fences. Delving even deeper, my earliest memory is only fragmentary: standing in the darkness, in the aisle of a movie theater and head high to the armrests, watching the big screen flickering black and white. What was it? My impression is that it was a newsreel, like the ones played before the feature film. History.

The end of memories is the beginning of history, and from the time before the house we have the stories, such as when my father felt it was time to find a wife. After finishing college he put out word to friends and relatives and promised $100 to the one who found his match. An aunt introduced him to my mother at a tea in Hong Kong. Though they spent only one afternoon together, my mother decided to take a chance because she wanted to go to America and rejoin the rest of her family, who had already immigrated to New York City years before.

Returning to the United States, my father needed a year to arrange the paperwork for my mother to reside here. Her flight from Hong Kong across the Pacific was on a noisy prop plane. Only 18 at the time, she was horribly airsick and frightened, and has never been on an airplane since. Despite the upsetting journey, my parents did manage to marry on Christmas Eve 1955, though my father somehow never paid the $100 reward to his aunt. Eventually they settled in Columbus and bought the house that would stay in our family until now.

Although he worked as an aerospace engineer, my father originally wanted to be a farmer. By the time he decided farming was too hard, he had already earned undergraduate and graduate degrees in horticulture from Ohio State University, which he attended under the G.I. Bill. My father had enlisted in the U.S. army in 1943 and trained in Florida for 13 weeks. For the remainder of World War II he served near Batangus in the Philippines, maintaining a power plant and helping to rebuild parts of the city.

Shortly after my mother was born, in 1937 near Hong Kong, most of her immediate family left for America in advance of the Japanese invasion of China, leaving her in the care of her grandmother. During the Second Sino-Japanese war (1937-1945) the two of them fled deep into the countryside, where they nearly starved and had to eat their dog (in one variation of this story, they merely had to eat “a” dog).

For a long time I wondered why my mother was left behind. Why she and her siblings here in the U.S. have different last names. Ng. Set. Yung. Only recently did I learn the history. The Chinese Exclusion Act, in effect from 1882 to 1943, had all but eliminated Chinese immigration to the United States. Some, with relatives already residing in the country, had the chance to join them after detention, scrutiny and interrogation on Angel Island, San Francisco. One by one, when they could, my mother’s family bought false identity papers and entered the U.S. as members of other families — so called paper sons and paper daughters — adopting new names and lives until they had even forgotten their own birthdays.

Not until the mid-1960s would Immigration Amnesty be granted, allowing those with fraudulent identities to become legal residents. My mother’s siblings could have reverted to their original family name, but each chose to keep the names they have lived with and been known by for so many years.

Like them my father had his own hidden history, which I stumbled on after finding his old Social Security card a long time ago. The name on it was Leon Ford, phonetically similar to Onn Fot, his real, legal name. When he was six, my father and his family came to the United States and settled in Ohio. Was he Onn Fot then and later became Leon Ford? When did he become Onn Fot again? I don’t know, he never talked about it; now his memory is uncertain and fading.

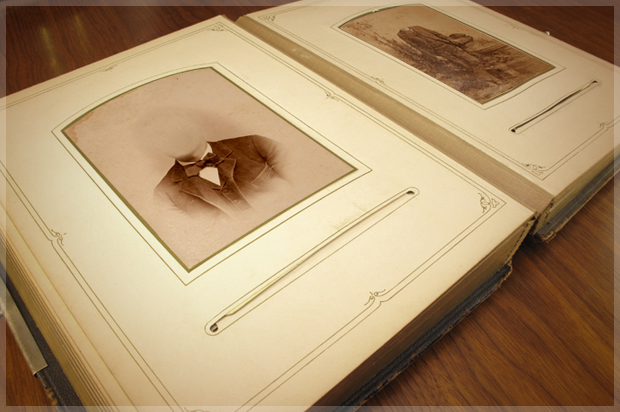

What else did I not know? I had always believed my father had only two brothers, until one day, when returning to the old house for a family wedding, I was looking through an ancient photo album. The pages were stiff, the sepia pictures cracked and faded. Then the photograph: my father, Uncle Toy and Uncle Charlie — all young boys in their home in China — with an older girl no one had ever mentioned. Eventually my cousins told me about the aunt I never knew. She had married and moved to Indonesia, losing contact with the family as was common back then.

Unlike my mother, my father, born in China in 1924, is a U.S. citizen by birth. How could that be? We never asked about the past and our parents never spoke of it. In the absence of facts, I had always imagined a great grandfather arriving in the United States to build the railroads; a grandfather born to him in this country and later moving to China to have his own children, who would be foreigners by birth but U.S. citizens by birthright.

A cousin who used to visit us at the old house only this year filled some gaps in the family history. For a time my father’s father lived in San Francisco and worked in a grocery store. How bad was China if opportunities were better stocking vegetables in America, thousands of miles from home? I picture a dark, stifling room in a tenement filled with Chinese men, all escaping war or poverty, working for money to send to their families. One of them had decided to return permanently to China and sold his citizenship papers to my grandfather, who then adopted that man’s identity.

I don’t know the year, but it was almost certainly after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which set fire to the city and destroyed public birth records. At the time almost anyone could claim to have been born in the United States and therefore were citizens — because no proof existed otherwise. If upheld, their children born in China automatically became U.S. citizens and would receive supporting documentation. So my grandfather was a paper son, and my father must be the paper son of a paper son, perhaps without even knowing it.

***

Once we had a family poem, now lost like so much else from the past. My father’s recollection of it differs slightly from what I’ve read about Chinese generational poems, so I don’t know if he misremembered or had lost some detail in translation. As he explained many years ago, family members (only men, I assume) received names corresponding to a word in the poem. All from the same generation drew names from words on the same line, and succeeding generations used succeeding lines. Perhaps because he was the youngest of three brothers, and as a paper son had changed family identity, my father was the last to be named this way — the 26th generation, according to the poem.

Twenty-six generations reach back some 900 years to an unknown ancestor, an amount of time beyond our personal histories, beyond our stories and deep into myth. It is a legacy I can’t fathom. If our family name, Lee, originated with a document bought in a crowded boarding house, then we don’t know our true lineage. Being a fully assimilated American, I don’t feel the loss acutely. For my own children, however, I wonder about the heritage they will never touch, like the old family house now sold and gone, which they will never visit. I exist between the immigrants in their 90s who remember the old country and their original identities, and my daughters in grade school who know only this country and have friends with roots in many other cultures.

What did my grandfather think a hundred years ago when he first stepped off the boat onto American soil? Did he feel the cold wind at his back and look at the hills of San Francisco, a city with all its chaos, activity and opportunity? Did he reflect on the long, hard journey across the Pacific? Or did he just focus on finding his way in a frontier so far from home? Ultimately, I believe his experience was the same as every other immigrant’s: sacrifice, risk, danger, loss, loneliness and, through it all, hope for a better life and a new home.