Donald Trump’s election has jolted environmentalists and voters who care about conservation. Trump has called for abolishing or greatly shrinking the Environmental Protection Agency; declared climate change a Chinese hoax; and promised to “cancel” the Paris climate agreement.

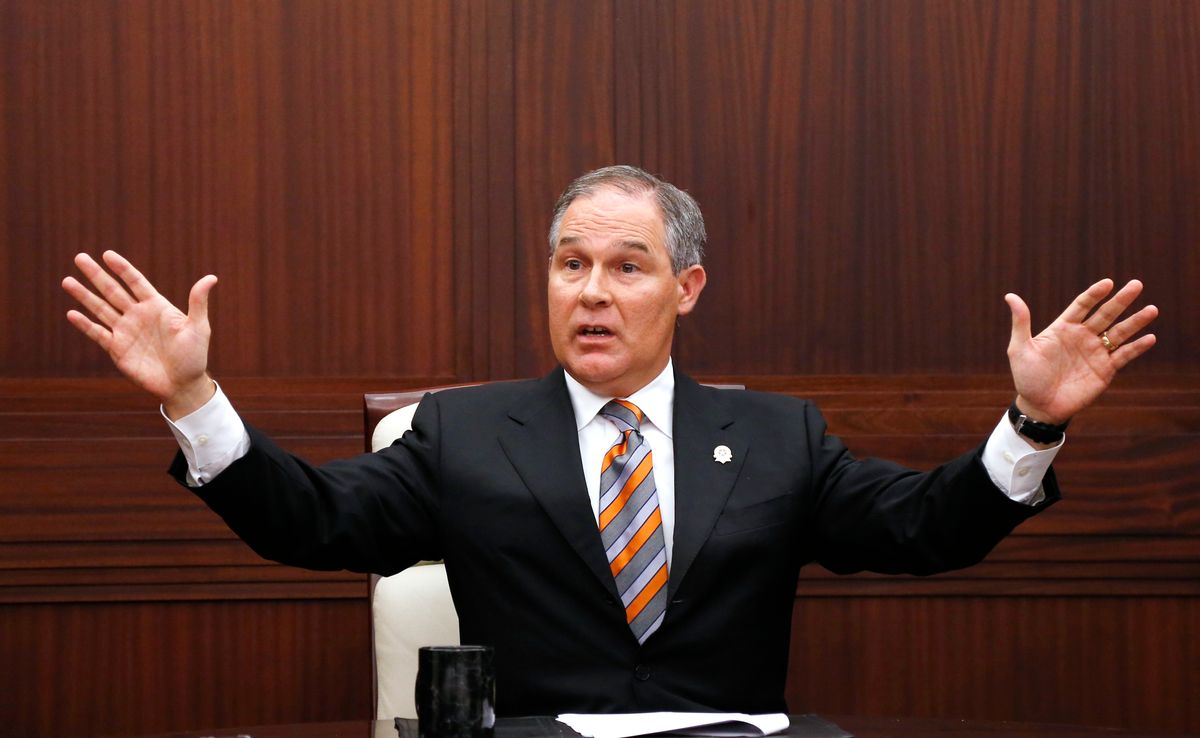

Though Trump appears to have backed off his pledge to “get rid of [EPA] in almost every form,” his choice of Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt to head the agency set off alarms in the environmental community.

Environmentalists were quick to denounce Pruitt, calling him an opponent of EPA who built his reputation by doing the bidding of fossil fuel industries. Is his appointment really like putting “an arsonist in charge of fighting fires,” as the Sierra Club argues?

Pruitt’s anti-EPA legal activism: Many lawsuits, few wins

A close look at Pruitt’s record reveals that he is a very smart, charismatic lawyer and passionate baseball fan who professes to care about protecting the environment. But his swift rise to national prominence was built on anti-EPA legal activism. Since his election as Oklahoma’s attorney general in 2010, Pruitt repeatedly has brought lawsuits claiming that EPA is illegally and unconstitutionally trampling states’ rights. These claims have won him praise in conservative circles, but little success in court.

Pruitt’s signature legal issue was his fight to block EPA from requiring coal-fired power plants in Oklahoma to install scrubbers to reduce pollution that impaired air quality in national parks. Pruitt’s legal arguments were rejected in 2013 by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, which ruled in favor of EPA, a decision the U.S. Supreme Court deemed unworthy of review.

Pruitt has repeatedly joined other Republican attorneys general in litigation against the Obama administration. In two cases, the Supreme Court ruled against their efforts to strike down the Affordable Care Act.

Pruitt has also sued other states. When he sought to invoke the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction to claim that Colorado had created an interstate nuisance by legalizing recreational use of marijuana, he quickly was tossed out of court.

In 2012 Pruitt and I testified on opposing sides at a congressional hearing. Pruitt’s congressional allies held the hearing to accuse the Obama administration of conspiring with environmentalists to settle litigation on terms unreasonably favorable to the environment. I described such claims as fanciful, but later a different kind of collusion emerged. The New York Times revealed that Pruitt had allowed an oil company to ghostwrite documents he sent to EPA. Pruitt’s defense was that he agreed with what the oil company had written.

On climate change, Pruitt has contended that the science is too uncertain and that the United States should not act because China will never agree to control its emissions. Both claims are demonstrably false, especially in light of China’s recent commitments under the Paris climate agreement. Pruitt joined the state of Texas in asking the Supreme Court to overrule its landmark decision holding that the Clean Air Act gives EPA authority to regulate greenhouse gases. The court refused.

Pruitt joined other states in suing to block EPA’s Clean Power Plan, the Obama administration’s signature rule to control emissions of greenhouse gases from existing power plants, a year before it even was issued. When the case was filed, my students unanimously predicted that it would be dismissed for violating a bedrock principle of administrative law: Only final agency action can be challenged in court. It was dismissed on precisely those grounds, but Pruitt has now sued again to challenge EPA’s final rule.

Can Pruitt roll back clean air and water regulations?

How would Pruitt change EPA? Clearly, given his record of fighting federal authority, states will have much greater leeway in their dealings with the agency. Pruitt wants to repeal the Clean Power Plan and EPA’s “Waters of the United States” rule, which seeks to clarify the limits of federal jurisdiction to protect wetlands. Both rules have been finalized and face court challenges from Pruitt and others.

Before adopting the rules, EPA was required by the Administrative Procedure Act to provide the public with notice and an opportunity to comment. EPA promulgated the Clean Power Plan only after considering 4.3 million public comments, the most the agency has received during its 46-year history. The water rule was adopted only after EPA reviewed one million public comments and more than a thousand scientific studies. Once rules are finalized, persons affected by them can ask a court to overturn them if they are not consistent with law or insufficiently supported by evidence.

After taking office, the Trump administration likely will announce that it no longer will defend the Clean Power Plan and the waters rule in court. But some states and NGOs have intervened to defend the rules, so litigation will continue. If courts eventually rule that EPA acted unconstitutionally or illegally when it adopted the rules, as Pruitt has claimed, they will strike the rules down.

But if Pruitt loses again and the rules are upheld, EPA will have to repeal them through the same notice-and-comment process it used to adopt them, as Pruitt has acknowledged. This will take considerable time.

To survive judicial review, EPA under Pruitt will have to articulate good reasons for repealing the regulations. When the incoming Reagan administration sought to repeal a rule requiring air bags on new cars in the early 1980s, the Supreme Court rejected the action as “arbitrary and capricious” because the evidence before the agency clearly supported the regulation. As a result, countless lives have been saved.

Pruitt might even try to take a radical step and reverse EPA’s 2009 finding that greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare. This approach is so clearly contrary to the weight of scientific evidence that it is doubtful it would survive judicial review. In 2011, when it reaffirmed that the Clean Air Act covers greenhouse gases, the Supreme Court cautioned that any EPA decision not to regulate them would be subject to judicial review and could be overturned if it was found to be arbitrary and capricious.

If EPA follows proper procedures, it eventually could repeal the Clean Power Plan and water rule because agencies have significant discretion in deciding to how to carry out the law. But as with President-elect Trump’s pledge to repeal the Affordable Care Act, the crucial question then will be what replaces them. If EPA’s finding that greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare stands, then EPA has an obligation under the Clean Air Act to control them. What approach will Pruitt use to do so?

The same question applies to the water rule. Pruitt has called this measure “a classic case of overreach,” but the rule simply clarifies preexisting limits on federal jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act. A decade ago the Supreme Court split 4-1-4 on this issue, creating enormous confusion that persists today. EPA based its rule on extensive study of how pollution affects various water bodies. Pruitt can either reinstate this confusion or try to revisit the science in a new rule-making.

As a long-time resident of Washington, D.C., I have no elected representative who will have a vote on Pruitt’s confirmation. But I hope that after he arrives in town his love of baseball will take him to Nationals Park, where he will discover a “politics-free” zone. As the new federal guardian of the environment, Pruitt should manage EPA as a “politics-free” zone devoted to environmental protection. But his track record of devotion to fossil fuel interests and hostility toward EPA make that prospect unlikely. Pruitt may find it easier to take apart EPA rules from the inside than his experience on the outside.

![]()

Robert Percival is a professor of environmental law at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Shares