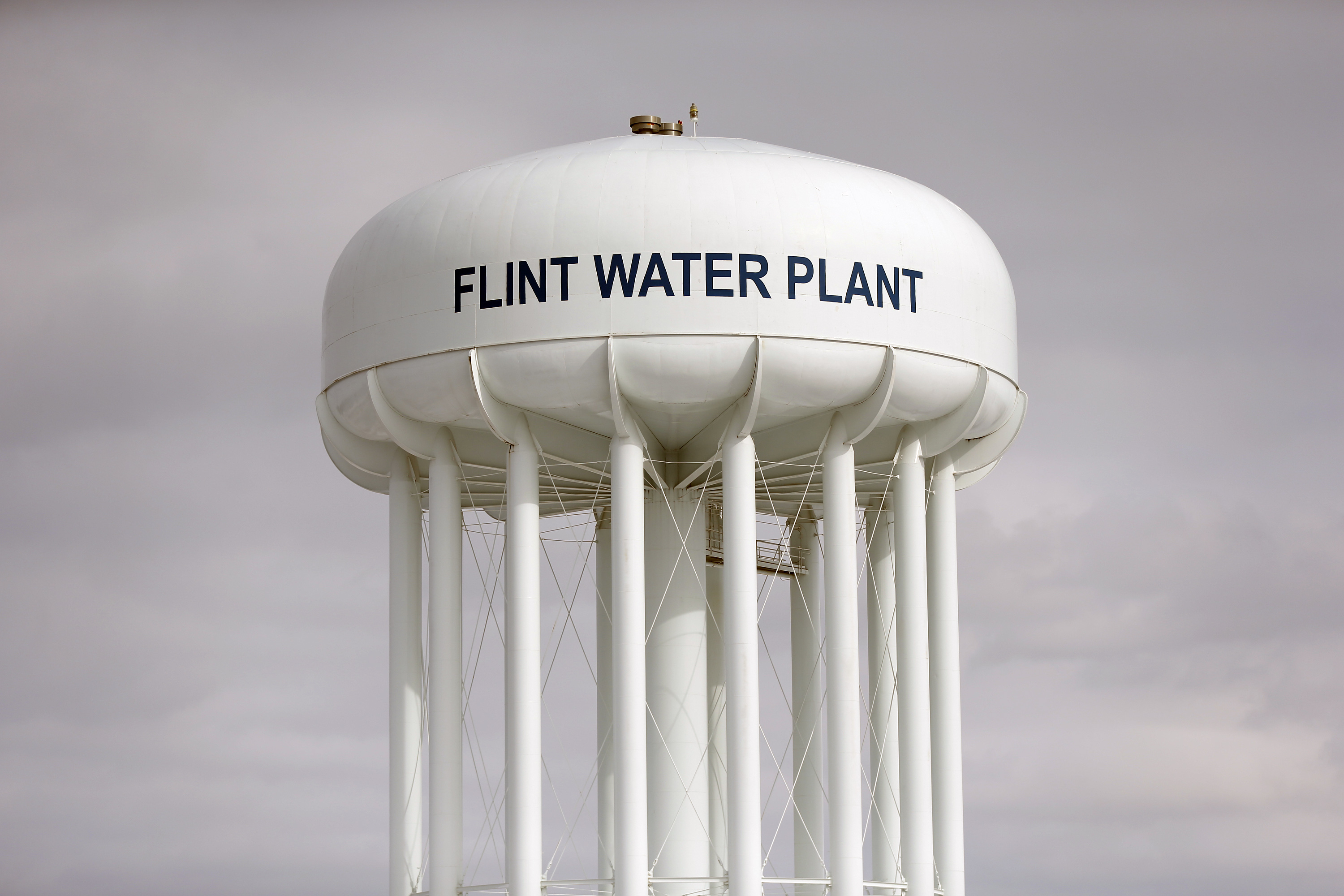

Flint’s lead-poisoned water crisis, which erupted in 2014, shined a global spotlight on the dangerous confluence of austerity, poverty and environmental racism. A new in-depth investigation by Reuters finds that Flint is far from alone, with nearly 3,000 areas nationwide facing lead poisoning rates “at least double those in Flint during the peak of that city’s contamination crisis.” In 1,100 of those communities, residents had lead levels in their blood that were four times higher than those found in Flint.

Journalists M.B. Pell and Joshua Schneyer made these determinations by examining neighborhood-level data from state health departments and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The poisoned places on this map stretch from Warren, Pennsylvania, a town on the Allegheny River where 36 percent of children tested had high lead levels, to a zip code on Goat Island, Texas, where a quarter of tests showed poisoning,” they wrote. “In some pockets of Baltimore, Cleveland and Philadelphia, where lead poisoning has spanned generations, the rate of elevated tests over the last decade was 40-50 percent.”

Reuters sent reporters to many of those impacted locations and they noted that “poverty remains a potent predictor of lead poisoning” but “victims span the American spectrum.” The report states that “like Flint, many of these localities are plagued by legacy lead: crumbling paint, plumbing, or industrial waste left behind. Unlike Flint, many have received little attention or funding to combat poisoning.”

Lead poisoning can have irreversible impacts on the brain. According to the World Health Organization, “young children are particularly vulnerable to the toxic effects of lead and can suffer profound and permanent adverse health effects, particularly affecting the development of the brain and nervous system. Lead also causes long-term harm in adults, including increased risk of high blood pressure and kidney damage. Exposure of pregnant women to high levels of lead can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, premature birth and low birth weight, as well as minor malformations.”

The CDC notes, “no safe blood lead level in children has been identified.”

“The disparities you’ve found between different areas have stark implications,” Dr. Helen Egger, chair of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center’s Child Study Center, told Reuters. “Where lead poisoning remains common, many children will have developmental delays and start out behind all the rest.”

In a February article published on Tom Dispatch, David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz referred to lead poisoning as America’s “coast-to-coast toxic crisis,” noting that it is rooted in political and economic factors. “[E]conomically and politically vulnerable black and Hispanic children, many of whom inhabit dilapidated older housing, still suffer disproportionately from the devastating effects of the toxin,” they wrote. “This is the meaning of institutional racism in action today.”

“As with the water flowing into homes from the pipes of Flint’s water system,” they continued, “so the walls of its apartment complexes, not to mention those in poor neighborhoods of Detroit, Baltimore, Washington and virtually every other older urban center in the country, continue to poison children exposed to lead-polluted dust, chips, soil and air.”