French marketing guru and cultural theorist extraordinaire, Clotaire Rapaille, explains in his book, "The Culture Code," that every culture has a coded way of understanding a particular topic. The cultural code for sex in America is “gun.” The theory is not as phallic as it seems, rather it explains that, for most Americans, sexuality is at once the source of excitement and danger. It is a powerful weapon, but a weapon indeed – something to treat with caution and approach with fear. Rapaille’s examination of America’s sexual psychosis explains why mainstream culture consistently oscillates between vulgarity and frigidity. Teenagers typically are thrilled with sex, but slightly afraid of it. In the adolescent American mindset, titillation and annihilation are flipsides of the same peep show token.

The weakness of Rapaille’s analysis is that it applies exclusively to straight culture. Gay men, seemingly far more enlightened on human sexuality than their heterosexual friends, for the most part avoid, at least in their art, the neuroses of loving and hating sex, while believing it is both everything and nothing at the same time.

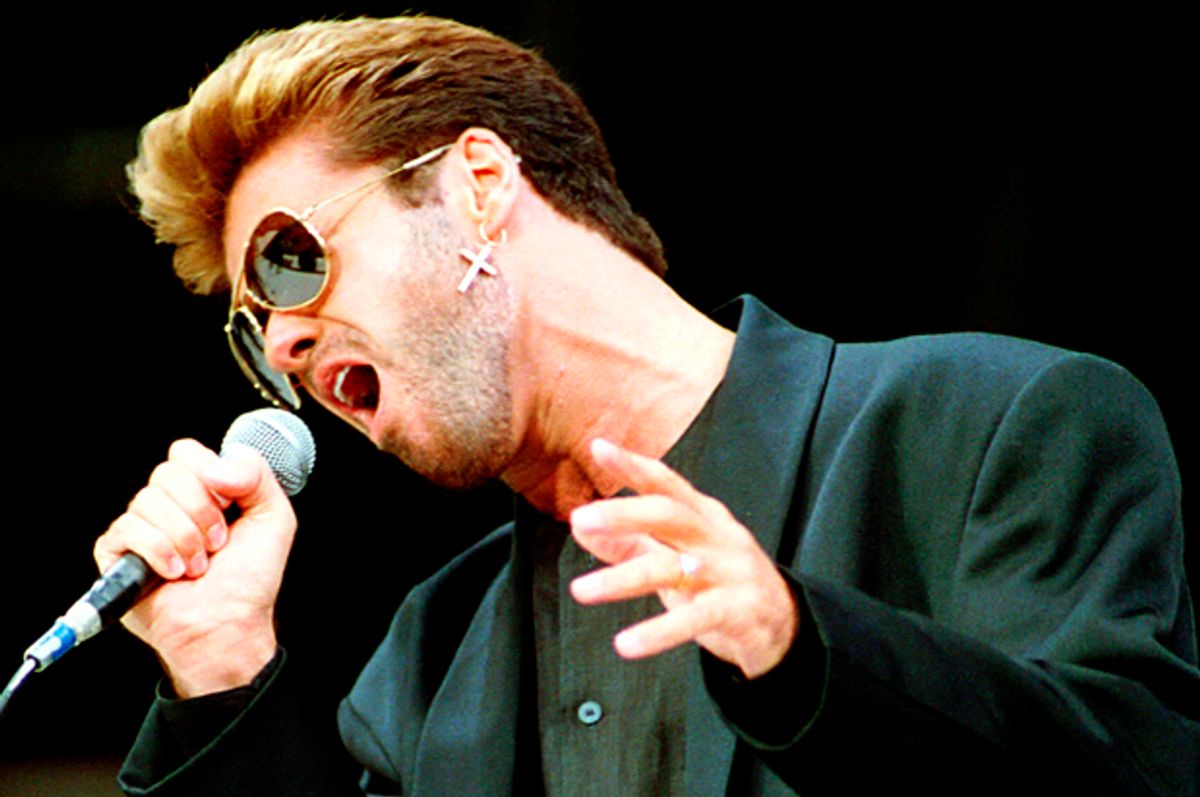

There were few more sophisticated and talented purveyors of a smart, free, and fun sexual ethic than the recently deceased George Michael. Throughout his music, sex is not dangerous, but an affirmational source of joy, creativity, and intimacy. It is also not a tool for conquest, or opportunity for domination, but an opportunity for mutual pleasure. Love is not a prerequisite for erotic ecstasy, in Michael’s musical architecture. The only regulatory mechanism is the insistence that all participation is voluntary, and all experience is reciprocal. In the 1980s, when heavy metal hair bands objectified women according to cruel routine, Madonna blurred the lines between submission and control, and hip hop began to flirt with misogynistic terminology, George Michael sang anthems of reciprocity — celebratory, dance hall epics of simultaneous orgasm.

“I know we can come together,” Michael sings in his masterful blend of pop, disco, and funk, “I Want Your Sex.” Since the British icon’s death, most critics have avoided discussion of “I Want Your Sex,” preferring to cite “Faith” and “Father Figure” from the same record as proof of his greatness. Perhaps, neglect of one Michael’s best songs is due to the heterosexual imagery in the video. Michael was still in the closet, and while it is now clear that the sex he wanted was not with a woman, he made it appear that way to appease his record label, and the homophobia of MTV viewers. It is also possible that commentators believe that the song, because it is indescribably fun, is not “serious.” Stanley Crouch once wrote that “there is nothing more serious than joy when it is about the right thing.” What is more joyful than sex when it is with the right person and done the right way?

In “I Want Your Sex,” Michael, with the aid of an infectious groove and booming voice, is able to combat against both the Puritans and the predators. “Sex is natural / Sex is fun,” he declares with the promise that he “won’t tease” or “tell lies.” He looks not for authority – “I’m not your father / I’m not your brother.” He seeks only “sex.” The refusal to sing in metaphor signifies the lack of shame he feels in his elevation of sexuality, and in his proposition. He doesn’t “need a Bible,” and he boldly asks, “What’s your definition of dirty baby? / What do you call pornography?”

One could interpret the inquiry as directed not only to the desirable subject of the song, but also the inevitable moralists who would object to the eroticism of Michael’s music. As countless rock and rap songs demonstrate, when a male performer challenges conservative mores surrounding sex, it is typically to announce conquest or issue command. Too many otherwise enjoyable songs of heterosexual seduction suffer under the possibility of exploitation. When a man demands sexual favor from a woman, one cannot help but wonder how the woman is supposed to feel. George Michael’s plea for physical attention and affection differs in that he makes it clear he is interested in bodily union only if his partner is a true partner in every sense of the word – an enthusiastic collaborator who will receive as much he gives.

In literature and music, gay men have demonstrated a stronger sense of sensuality that many straight chroniclers of lusty ambition. Walt Whitman, whose sexuality is still the subject of debate, was either gay or bisexual, but seemed to have perfect comprehension of mutual pleasure when he classified sex as “the merge.” Sex was a democratic act, in Whitman’s experience and imagination. “Who be afraid of the merge?” the poet asked, and while Michael would have answered no one, many would cower in the corner.

Cowards emerged with pride when Gore Vidal wrote America’s first mainstream novel offering a man-on-man love affair as natural and normal, "The City and The Pillar," in 1948. The story is one of sexual confusion. Its protagonist is attracted to men, but he cannot act on his desires, because of the suffocation of America’s moral regime. When he does find opportunity for sexual thrill — in gay bars or with closeted acquaintances — the sex is without love, but also without neuroses. It is only at the novel’s conclusion, when the protagonist confesses his feelings for his boyhood love, and the man reacts violently, that the main character forces himself on the object of his carnal dream. The rape is a result of homophobia as much as it is due to personal depravity. Both men know that they are gay, but one is too afraid to exercise his ineradicable impulse.

George Michael sings in his anthem, “Freedom,” “All we have to see / Is that I don’t belong to you / And you don’t belong to me.” The beautiful simplicity of those lyrics captures the egalitarian spirit, always at war with oppressors, but also the formula for great sex. While heterosexuality masculinity too often asserts itself as the owner of anything effeminate, gay men, through art, offer instruction in reciprocal ethics; A lesson that begins in the bedroom, but can apply with equal power and pleasure to the boardroom.

Sylvester, one of America’s most underrated musical innovators, sang anthems similar to Michael’s libertine burners. The self-proclaimed “queen of disco,” who sang in a gospel falsetto that would influence none other than Prince, often performed in drag, and proclaimed the joy of feeling “mighty real” in the throes of love and ecstasy. The final record he released before dying of complications from AIDS, "Mutual Attraction," was one long documentation of the joys of “what makes the world go around,” as the title suggests.

The executives of Sylvester’s record company believed mainstream success was within striking distance, but only if he began to wear men’s business suits, and adopt a publicly straight persona. In an act of heroic courage, Sylvester refused to comply. In fact, when he appeared at a record company gala shortly after rejecting corporate demand, he wore a pink gown.

George Michael displayed the same defiance when, through the mystery and bravery of artistic alchemy, he transformed scandal into success. After Beverly Hills police apprehended Michael in 1998 for soliciting anonymous sex in a public park with a reputation as a late night, gay cruising site, he composed an irresistible dance song, “Outside,” boasting of his predilection for alfresco fornication. Sampling radio reports of his arrest, along with squad car sirens, Michael sings, “Glad to meet you / This is human nature,” in an affected baritone. “Let’s go outside / In the moonlight/…Take me to the places I love best,” he continues over a dance beat; joyfully announcing his own sexuality, while denouncing the public shaming rituals that demand apology and abdication in Hawthorne style.

Two years earlier, Michael had animated his pride at making the ideal partner for “fast love,” with the power of danceable soul, and on “Too Funky,” he promises heaven if he can “get inside you,” but adds the crucial caveat, “If you let me.” Only “Outside,” however, amplified the flick of the middle finger to his sexual antagonists. As the song’s words and music make clear, Michael’s sexuality is always consensual. Reciprocity enhances its satisfaction, as does rebellion.

It is significant that Michael migrated to the black side of town when searching for a musical home. The triumph of his 1987 duet with Aretha Franklin, “I Knew You Were Waiting,” made him one of the first white artists to nearly top the then anachronistically named “black chart.” Reviewing Michael’s significant contribution to music, Michael Eric Dyson recently wrote, “George Michael fashioned a powerful aesthetic from the rhythm and blues base that shaped his music, and his art reveled in the black culture that offered him solace as he struggled to claim his identity as a proud gay man.”

Much of black culture and gay culture share an emphasis on pleasure, the celebration of which originated as a protest against any external effort to execute the humanity of its participants. “Champagne and Reefer,” by Muddy Waters, and Michael’s “Outside” are best understood as protests songs — the creations of artists, but first and foremost human beings, who dance in the frown and grimace of the tyrant; Men who refused to accept restriction on the liberty and mobility of their minds, souls, and bodies. “There’s nothing here but flesh and bone / There’s nothing more…” Michael sings on “Outside.”

Whites and heterosexuals, operating under the assumption of their natural superiority, often betray a belief that if blacks and gays adopt their behavioral norms, they will become happier. The dominant culture demands conformity not always with malice, but with the intention, perhaps even more destructive, of assistance. “We know what’s good for you,” is precisely the condescension that Michael rejected in the bravado of his sexual self-expression.

It is an instructive irony that on the matter of rejecting miserable priggishness, and pursuing the sexual joy of mutual pleasure, gay men might know what is good for straight romance.

Shares