The day after John Berger died, a friend posted a video on my Facebook page of two Moluccan cockatoos at a tropical bird zoo and sanctuary in Tennessee. In the video, one of the enormous white birds unleashes a peal of laughter so uncannily human that the two women behind the camera squeal and giggle, inspiring the bird to laugh more. It cackles, throwing back its head and flaring its lavish white-and-orange crest. The women shriek with delight. The bird twirls on its perch, now fully working its audience, which in turn provides increasingly shrill appreciation.

The video is funny for about 20 seconds, but as the laughter escalates, I begin to feel uncomfortable, even embarrassed. In the background, the second cockatoo, my stand-in, looks on quietly and then turns away. The clowning bird whoops and poses, but the silent one hunches from the camera, its discomfort seeming to channel my own. This has happened before, perhaps hundreds of times.

The most excruciating moment comes in the final seconds of the clip, when even the flamboyant bird seems to lose interest in the forced hilarity. One of the women, now visible in the frame, tries to keep the spectacle going by further imitating the bird’s artificial laugh. She mimics the bird mimicking her. The scene has become a feedback loop of reciprocal parroting so grotesquely divorced from any genuine humor that the effort falls painfully flat. I could barely watch to the end.

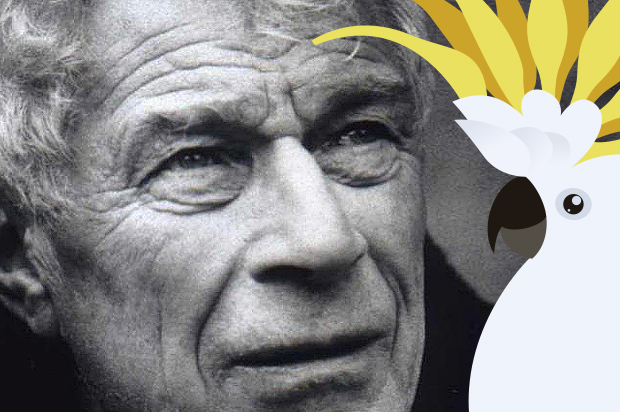

Berger was eloquent and devastating on the subject of zoos. Although he wrote of trips to the zoo with his father as “one of my few happy childhood memories,” he also viewed these institutions as the final installment in a millennia-long story of human-animal relations, one that doesn’t end well.

Animals had always held a central place in human lives, he argued — both physically, as food and clothing, and psychologically, as myth and metaphor — but in the 19th century, industrialization, sprawl, colonialism and the wholesale acceptance of Descartes’ distinction between mind (human) and matter (everything else) initiated the large-scale marginalization of animals. Today, Berger proclaimed, in every real sense, “we live without them.”

The wild animal was replaced with its mirror twin: the exotic captive, living harmlessly in a simulated landscape. Early zoos offered both a showcase for the gorgeous spoils of imperialism and a repository for our nostalgia, Berger writes in “Why Look at Animals?,” his famous 1977 essay. “The zoo to which people go to meet animals, to observe them, to see them, is, in fact, a monument to the impossibility of such encounters. Modern zoos are an epitaph to a relationship which was as old as man.”

It’s a gut punch, this assessment. And good intentions underlie so much of the work done in modern zoos, to be sure. But who hasn’t experienced both the wistfulness and disappointment Berger describes upon any visit to a zoo, when the animals “seldom live up to the adults’ memories, whilst to the children they appear, for the most part, unexpectedly lethargic and dull?” (Cockatoos, perhaps, notwithstanding). Not only do we not find the wild creatures we were hoping for, but we fail to locate our memories of them. Without natural context, and stripped of any agency, they are little more than replicas of themselves. Pretty sad ones.

“However you look at these animals, even if the animal is up against the bars, less than a foot from you, looking outwards in the public direction, you are looking at something that has been rendered absolutely marginal; and all the concentration you can muster will never be enough to centralise it.” Bars aren’t the norm anymore, but the sentiment stills feel true.

Of course, the cockatoo clip — and the funny-animal video genre to which it aspires — is a further step removed, as Berger would surely remind us, since we are viewing this interaction from a distance and through the frame of the camera. That added step charms and anesthetizes simultaneously. All stakes have been removed. If zoos are monuments to conquest and memorials to a bygone wild, then animal videos are a new way of commodifying the irrevocable loss of that crucial link. They’re currency — based on absence and longing — that we trade for likes, attention and even, thanks to video ads, actual money. These trinkets pacify and cajole us during dark times (“get me a capybara video STAT,” a friend texted me in the days following the election), like a stuffed rabbit cheers a crying child. The advent of realistic animal toys roughly coincided with the creation of public zoos, Berger also notes.

Does the Moluccan cockatoo even exist in the wild? It’s a question most of us, so accustomed to seeing pet birds doing goofy things in videos, have never asked. In fact, it’s a native of Indonesia, and like many of its gregarious avian cousins, is classified as vulnerable, thanks to poaching for the pet trade and habitat loss. Google instantly wonders, when you search on the species, if you’d like to know its price.

Because of their ability to mimic human speech, parrots and cockatoos, more than other species, never really had a chance. Officially we are against anthropomorphism — it is practically taboo to attribute human emotions to animals in any serious journalistic or scientific forum, for example — but on the sly, when our respectable minds aren’t looking, we are mad for it. Our apartments overflow with pets, some of whom wear clothes and play pianos. Our theaters and TVs brim with cartoon animals rapping and making timely pop-culture quips. But unlike in the days when early humans looked to animals to help explain their origins, these replicas are our own dancing shadows, emptied of their individual meanings and plumped out with our own. How much better, then, if they cheerfully play along, singing, swearing and dancing to Pharrell?

A little more anthropomorphism may be just what’s needed to bring animals back from the margins. Laughing cockatoos and screaming goats could be awakening a new kind of anxiety in us — a crude kinship with and concern for these others that’s sorely lacking in our farming regulations, conservation policies and pet purchasing habits.

Like the quiet cockatoo that turns away, maybe we will simply grow weary of the spectacle, longing for something real.

It’s a long shot.

“You’re mocking me!” the woman in the video says to the cockatoo, and it’s hard to disagree with her.