On election night a murmur started just as the last gasp faded, “Well at least we can expect some great art.” At first the sentiment was a fatalistic one-off, a brave face, a shy hope that something good would come from the dark days forecast for the Trump presidency. It didn’t take long for the statement to acquire a predictive tone, eventually a waft of desperation was detectable and, ultimately, shrill fiat.

The art of protest is provocative, no question. It’s often brave, usually fierce, sometimes compelling and occasionally inspirational. But is the appeal of the books, films, poetry, painting, television and sculpture produced in response to tyranny, oligarchic pomposity or a fetishistic prioritization of the bottom line universal or simply reactive? How durable is the art birthed from protest? The following essay is the first in a series for Salon exploring the question, do bad times really inspire great art?

It was the autumn of 1990, and I was sitting in the back of a Cadillac. We had just left a breakfast honoring the playwright Arthur Miller and we were now on our way to Orchestra Hall to hear him deliver his keynote address at the Chicago Humanities Festival.

The breakfast had been held at the Drake Hotel and was attended by young writers and well-heeled potential donors. Miller was in a foul mood that morning and seemed only to be interested in talking about the fact that, while his newest plays were lauded in England, he couldn’t find anyone to back them in America. At one point during the breakfast, I asked Miller if we could talk about his inspirations or his writing process or maybe even the decline of regional voices in the American theater — I was a big fan of his and I had been excited to meet him, but why were we spending the whole time talking about money?

“Because that’s the whole ballgame,” he said.

In the Cadillac’s front seat, there was a wealthy, retired couple; they had also gone to the breakfast and had offered to give me a ride to Miller’s speech. Probably some part of me was hoping I’d found a benefactor. So, as we rode south on Michigan Avenue, I told the couple about the sort of writing I was doing and the plays I wanted to produce.

The woman stopped me mid-sentence. “I know this will disappoint you, Adam, and I’m sure it would disappoint Mr. Miller too. But I don’t believe that ‘comfortable people’ should be supporting artists at all,” she said. “I believe the best art is made by people who are struggling.”

* * *

As the Trump era looms before us, it’s tempting to take solace in the belief that awful times lead to the creation of brilliant art, that an artist’s struggle was what made his or her greatest masterpieces possible. Sure, nearly 20 million died in World War I, but at least that tragedy gave us “All Quiet on the Western Front.” The Depression gave birth to “The Grapes of Wrath, Modern Times,” Diego Rivera’s murals, the songs of Woody Guthrie and the best plays of Arthur Miller. And no, we wouldn’t have “The Naked and the Dead” or “Catch 22” if Norman Mailer and Joseph Heller hadn’t fought in World War II.

We could go on for quite a while, pairing grim historical events with the art they helped to produce: Kristallnacht with “The Great Dictator;” Hiroshima with “Rhapsody in August” and “Hiroshima, Mon Amour.” Vietnam with “Masters of War” and “Fortunate Son”; Watergate with “All the President’s Men” and the classics of 1970’s paranoia cinema; Reaganomics with Bad Brains and Minor Threat; Margaret Thatcher’s England with The Sex Pistols and The Clash; AIDS with “Angels in America.” But this line of thinking only gets you so far; at some point, maybe when you start discussing the Holocaust and “The Diary of a Young Girl,” it just gets ghoulish.

Still, there’s no shortage of think-pieces or uncomfortable conversations in plush, south-going Cadillacs to teach us that the worse our times get, the better art we get too, that, in fact, the very best art is made by people who are struggling.

Back during the crash of 2008, Nicholas Dawidoff, writing for the Wall Street Journal, credited the Mississippi flood of 1927, which rendered nearly 1 million people homeless, with helping to create the blues. “A long-standing American artistic tradition of making crisis and hardship into something beautiful exists,” Dawidoff wrote.

In the same year, Chicago Tribune critic Julia Keller authored a piece headlined “The Worst of Times Can Make for the Best of Arts.” “While it was a time of hardship and suffering on a massive scale, the Great Depression also was the crucible for many exquisite works of American art,” wrote Keller.

“Bad times make good literature,” offered John Egerton in his 1994 book “Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South,” as he discussed the Harlem Renaissance. “There’s so much good material.”

It would be nice to think that, as Donald J. Trump readies his cabinet featuring a rogue’s gallery of heavies straight out of some misbegotten Ayn Rand novel, we are on the cusp of a new American artistic renaissance, one full of good material. But I wouldn’t be too sure about that.

For one thing, we’re in the wrong era. A lot of the structures that helped art to emerge from dire circumstances are no longer in place. Zora Neale Hurston and Eudora Welty worked for the Federal Writers Project, which flourished during the 1930’s; at one time, John Steinbeck worked for Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, which lasted until 1943. Among those employed by the WPA’s Federal Art project were Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner and Mark Rothko. After leaving the armed services, Norman Mailer and Joseph Heller attended college on the GI Bill. And so, by the way, did Paddy Chayefsky, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Frank McCourt and Robert Rauschenberg.

Does anybody really foresee a new New Deal supervised by rumored NEA chief Sylvester Stallone?

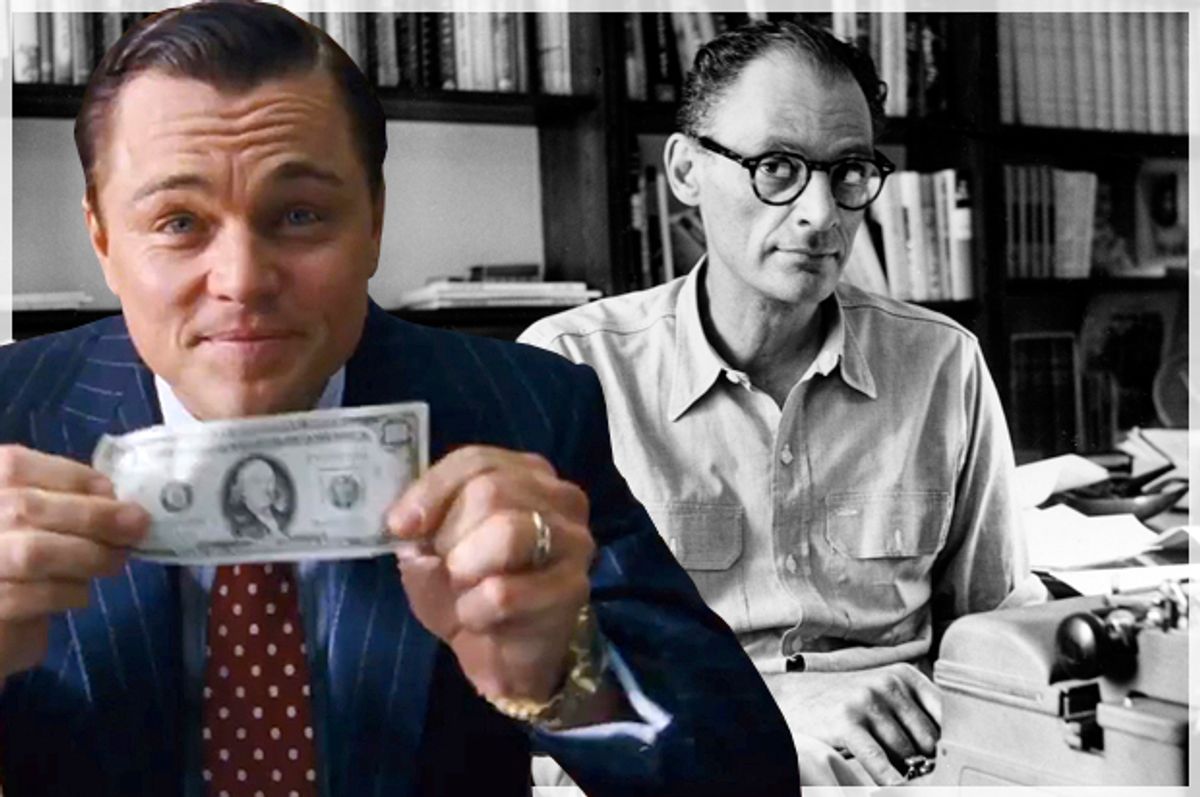

When people write of the glorious art that arose out of dreadful times, the examples they cite tend to be at least 25 years old. Yes, a few solid novels have been written about our post 9/11 world — “Netherland” comes to mind. The Iraq war has given us a few terrific books (“The Yellow Birds”; “Redeployment” “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk”), a couple decent movies (e.g. “The Hurt Locker”) and some lousy ones (e.g. “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk”). But what great art has been created out of the housing bubble and recession of 2008? Okay, I liked “Margin Call” and the first half of “99 Homes,” and “The Wolf of Wall Street” was watchable enough on a transatlantic flight, but you’d have trouble saying they constitute any kind of movement.

These days, we have different expectations for art than we once did. Artists are allowed less time to process events and respond to them. Erich Maria Remarque published “All Quiet on the Western Front” a decade after the end of WWI, but today, as I write this, the events of November, 2016, already seem to have taken place during some previous generation. The Twitterverse moves so quickly that it can sometimes feel pointless to try to be relevant; the best you can hope for is to respond honestly to the world around you and hope you’ll wind up seeming prescient. Maybe the best film about the Trump era will actually turn out to be the Mike Judge film “Idiocracy,” which was released ten years ago; maybe the best representation of red state America will be the just-concluded TV series “Rectify;” maybe the best novel about the 2018 Sino-American war will be one that’s being written right now.

Anyway, here in the dawn of 2017, I’m much more concerned about the artists we’ll be losing than the ones these times will be inspiring — those who’ll be deported then sent to live behind some wall; those who’ll lose their health care benefits after the repeal of the Affordable Care Act; those who’ll be priced out of their homes and forced to move to dangerous Ghost Ships; those who won’t be able to afford college anymore or who will be blacklisted because their names are on some Muslim registry or who won’t get their projects funded by a gutted NEA. Does anyone in Aleppo now have the luxury to contemplate writing the Great Syrian Novel? And could it even be distasteful to wonder if they might?

Will great art emerge from these times? Of course it will, as it always does, but in spite of artists’ struggles, not because of them.

And that, as a great writer once said, is the whole ballgame.

Shares