Let’s start with one of art history’s great quotations, attributed to René Magritte: “A face isn’t a face unless it’s facing you.” I’ll get back to you on that, but first, a brief foray into Bosnian standup comedy.

A Bosnian comedian residing in Slovenia isn’t the sort of person you’d expect to inspire deep thoughts on Surrealist painter René Magritte, Existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the neuroscience of facial recognition and the history of self-portraiture. But then again, Perica Jerković is no ordinary comedian. There are comics whose only goal is to be funny. And there are those who have a message, a philosophical bent, and their means of delivery, of prompting you to think deeper, is through comedy. Lenny Bruce was perhaps the ultimate example of this — he wasn’t particularly funny, just a sly and subversive observer. Louis CK, one of the most successful comics in the world now, is another such performer. Dave Chappelle offers true socio-political insight, but with a disarming drawl that allows deep ideas to infiltrate, flying in through the open-mouthed laughter of his audience. There are comics who sound (or look) dumb, but are actually cloaking insight: Steven Wright, Mitch Hedberg. At a recent one-man show by Jerković, "The History of the Dumbass Selfie," all of these characteristics were wrapped into one act. My inner art historian laughed his inner ass off, and it got me thinking. Add to my interest in self-portraiture this wild trend in “selfies,” plus a jigger of Magritte (my favorite artist, whose major retrospective ends this month at the Centre Pompidou in Paris) and a recent interview I did with Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist Dr. Eric Kandel. This odd, but surprisingly apt, cocktail was all inspired by a standup comedy performance that was much smarter than it needed to be.

Jerković’s show employs an enormous prop iPhone that stands erect behind him, looming like the monolith surrounding by apes in the opening of "2001: A Space Odyssey." It variously displays the home screen, phone calls from friends, photos (including selfies) and works of art that he discusses, professor-style, as he stands before them. The theme of his show is how “selfies,” this wildfire phenomenon defined as “a self-portrait photograph taken with the intent of posting it online,” is really a cry for attention in a world overrun by images and information. Some statistics: around 93 million selfies are taken worldwide each day. The average millennial will take more than 25,000 selfies in their lifetime. Some 24 billion selfies were uploaded to Google in 2015. That’s a lot of (largely uninteresting) self-portraits. They’re also potentially deadly: Since 2014, at least 49 people have died while taking selfies, all of them under the age of 33.

In the face of this typhoon of data vying for our attention, we find a measure of self-actualization in the 16 “likes” that friends proffer our duck-faced self-portraits. It mixes a sense of desperation, vanity, hunger for attention, and pathos: like a swimmer in choppy waves, surrounded by kilometers of open ocean, waving with one water-logged hand and admiring themselves in a mirror with the other. It’s also a modern mode of “bookmarking,” like carving one’s name in a tree — witness the thousands of visitors snapping selfies in front of the "Mona Lisa" (without necessarily taking the time to look at the painting) — the selfie is “proof” that you were somewhere or, if we’re getting a bit more melodramatic, that you are someone.

This is nothing new. Millennia of portraiture has maintained the same goals. Instead of the selfie-stick and that democratic, worldwide, instant gallery called the Internet, past eras have employed pens, brushes and chisels, and understood that the memory of how artists or their subjects looked was limited to what artists could craft, and by the knowledge that relatively few people would ever see them. Artistic skill was needed to produce a true likeness (though realism was not always the goal), so “selfies” of the pre-photography era were limited to artists, and often took the form of carved signatures rather than pictures. Commissioned portraits, therefore, should enter the discussion, since there are far fewer historical self-portraits than portraits. Until the 18th century, artists' materials were expensive enough that artists rarely painted or sculpted if not on paid commission. Heads of state, clergy and wealthy patrons would commission portraits in order to preserve their likeness but, official state propaganda aside, this was often just for their family and honored guests, not intended for the general public, and certainly never envisioned for whitewashed gallery walls hundreds of years into the future.

Portraits, like selfies, were “curated” by those who made them. Imagine if only one photograph of you would ever exist, just one online to preserve your likeness. You’d think pretty carefully about how it should look, right? A survey of 2000 young women found that they spend an average of 16 minutes a day taking selfies (where did they find these study subjects?), which means that a lot of pictures are being deleted for every one that makes the cut. Those who commissioned portraits would ask to be shown as they liked to think of themselves, and as they would like to be remembered: often prettier than they were in person, surrounded by positive attributes that may, or may not, have actually featured in their lives. When Piero della Francesca painted Federico da Montefeltro’s circa 1465 portrait in profile, he was not only referencing ancient Roman portraits of emperors in profile on coins, but also hiding the battle-scarred right side of his face by showing only his left. The bridge of his nose had been smashed and his right eye lost in a tournament, and it would have frightened the young’uns had he been preserved for eternity fully frontal. Airbrushing is a longstanding tradition. Thus selfies, like portraits, are not completely honest records of appearance, but rather a carefully selected version of how we would like to be seen by others.

But how, exactly, are our faces seen? In interviewing Dr Eric Kandel, he of the 2000 Nobel Prize for his neuroscience breakthroughs on human memory (achieved with the assistance of giant sea snails, of course), he mentioned parallels between how the brain processes art and faces. In fact, the same part of the brain deals with art and facial recognition.

The inferior temporal gyrus helps us distinguish and categorize things we see. Within that section of the brain there are several subsections, including the fusiform gyrus, also called the Fusiform Face Area, which specializes in recognizing faces (as opposed to objects and landscapes, which are the realm of the Parahippocampal Place Area). The Extrastriate Body Area distinguishes the human body from other objects, while the Lateral Occipital Complex analyzes specific shapes as opposed to abstract or indistinct ones. In my previous article, “This Is Your Brain on Art,” I examined Kandel’s breakthrough analysis of the Lateral Occipital Complex: how the brain deals in surprising ways with formal versus abstract art. Turns out that the same region of the brain is also in charge of face recognition.

When playing hide-and-seek with my daughters, they’re fine with my lurking in a shadowy corner and jumping out as they approach. But if I stand anywhere, even in full light, with my face covered, they totally freak out. They logically know that it’s me, but when my face is obscured, a part of their brain kicks into panic mode, because I just might be a monster.

And so we come to Magritte.

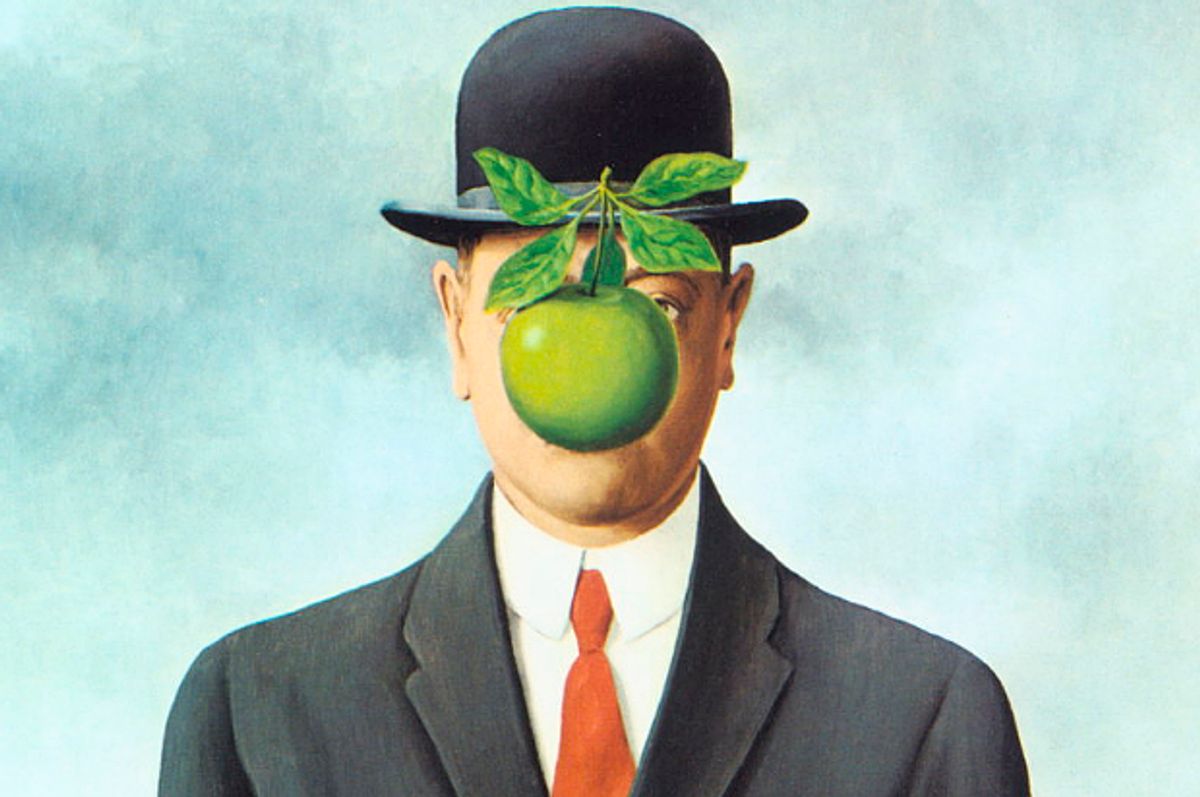

Consider Magritte’s 1964 painting, "Son of Man." It portrays an anonymous businessman in a bowler hat and a suit, his face obscured by a floating green apple. Magritte most admired the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre wrote of the confrontational nature of the exchange of gazes between people. The refusal to meet the gaze of another is akin to the refusal to acknowledge the humanity, the soul, the existence of the other. The refusal of offer another person your gaze, to obscure your face from them is, for us humans, monumentally creepy (just ask my daughters).

We do not feel that we “understand” a person if we do not see their face. Could you recognize the businessman in Magritte’s "Son of Man?" Perhaps, you might suggest, by his clothing. But what about another Magritte painting, entitled "Golconda?" This portrays a suburban street, with hundreds of identical businessmen in bowler hats suspended at various points in the sky, as if it is raining businessmen. Their faces are blank. And his "Not to Be Reproduced" shows the back of a man’s head as he stares into a mirror — which reflects only the back of his head. It’s the stuff of horror films.

In portraits, self-portraits and selfies we create a version of ourselves that we want the world to see, and by which viewers should remember us. It is an art form, and because faces are its subject, it happens to provide double duty for the same part of our brains. We feel we understand someone, identify them, remember them, “read” them only when we see their face. To deny someone the sight of our face is to deny them our humanity, to monsterize.

“A face is not a face unless it is facing you.” A person is not a person if we cannot see his or her face. And we would have you believe that we are who we are, based on the face of ours that we carefully select to show you.

Shares