In Dec. 2016, the Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) denied an easement that would have permitted the company Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) to complete one of the final segments of the 1,100-mile Dakota Access Pipeline, which seeks to connect the oil fields of North Dakota with terminals and refineries in Illinois.

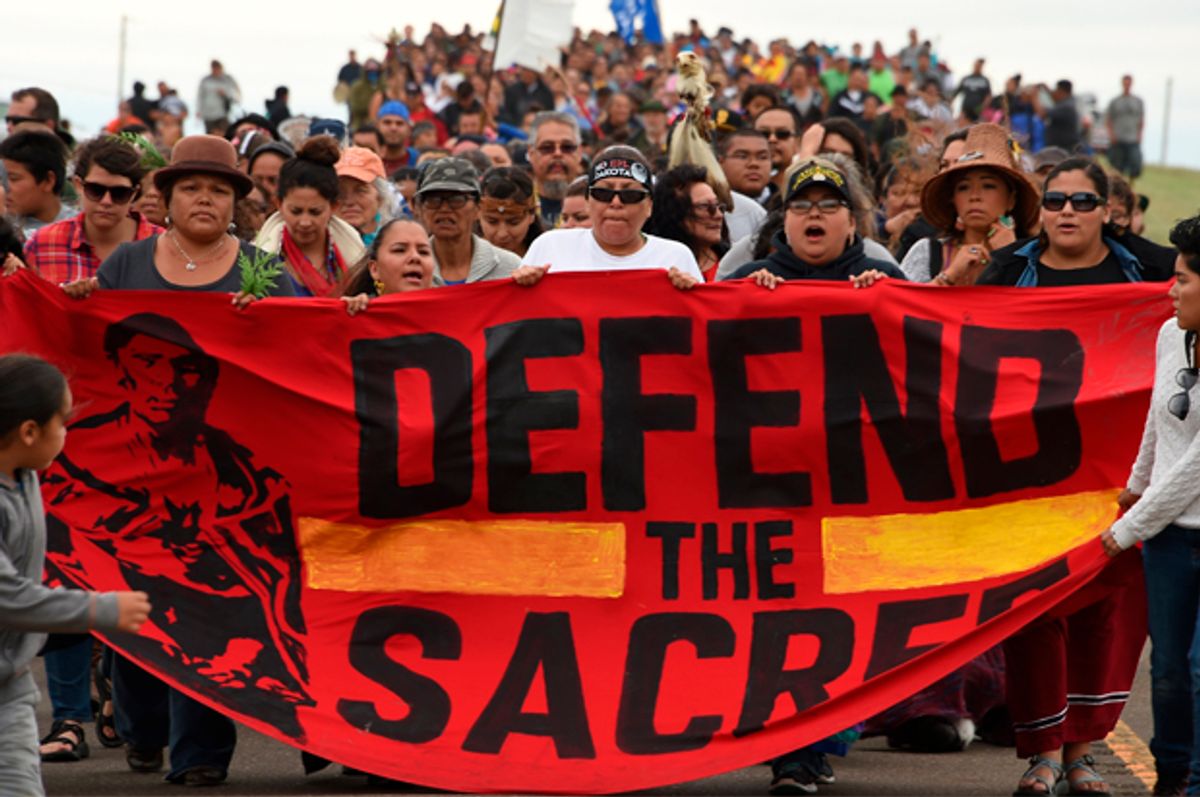

The denial of ACE’s easement is undoubtedly a victory for the Standing Rock Sioux. The tribe and its allies in the #NoDAPL movement opposed the pipeline over risks to water quality, the destruction of cultural heritage and the injustice of, once again, having to make sacrifices for the economic gains of others. David Archambault II, chair of the tribe, thanked those who had been gathering for months at the construction site, saying their “purpose had been served,” and that they may leave now.

But as we start a new year, many people are convinced that the need for resistance has not ended even after the tribe’s monumental victory. The Sacred Stone camp, a Spirit Camp dedicated to stopping the pipeline, published the headline “DAPL Easement Suspended, but the Fight’s not Over.”

As an indigenous scholar and activist, I agree that the water protectors’ underlying causes in this high-profile resistance have not been addressed — even if ETP truly halts all construction. Here are five developments people should consider as the incoming Trump administration takes power.

1. Tribal consultation requirements need to be reformed.

In its December memo, the ACE said it did not violate its duty to consult tribes in advance. Moreover, in ruling against the tribe, which had sought an injunction to halt construction, district judge James Boasberg documented the many efforts ACE made to reach out to the tribe as well as efforts of the pipeline builders to avoid damaging places of cultural and historical significance.

Yet nonetheless, the Standing Rock Sioux tribe’s territory was targeted for the pipeline instead of an area closer to Bismarck, North Dakota, which speaks to the need for reform of tribal consultation policies.

In my personal review and interpretation of ACE’s specific tribal consultation policy and the related Executive Order 13175, I believe agencies can fulfill the duty to consult with tribes without really giving them a fair opportunity for free, prior and informed consent. Some scholars argue that Section 106 policy of the National Historic Preservation Act, which requires impacts on cultural heritage to be considered, is not designed to fairly consider tribes’ interests.

Finally, when I reviewed Judge Boasberg’s opinion, what stands out to me are the multiple times when the tribe expressed objections and concerns to ACE and also ETP. Nevertheless, the agency and business interests kept pushing on. This is despite what should have been widely known about the significance of a 1868 treaty area for the tribe and its involvement in a 2012 resolution against future pipelines.

Some critics of the #NoDAPL movement, including a North Dakota congressional representative, claim that opposing the pipeline offends the “rule of law.” Yet, for me, this criticism is unclear.

Morally speaking, I believe current tribal consultation policies lack strong enough support for the right to free, prior and informed consent and fail to protect sufficiently religious freedom and cultural integrity. Legally speaking, the United States has a long way to make up for a range of unlawful actions, from breaking treaties to swindling indigenous trust assets. In my view, basic respect for the Standing Rock’s treaty rights over the years would have made the current situation unlikely. Such respect would have also, speaking more speculatively, put many tribes in stronger positions, both economically and in terms of government capacity, to negotiate and track the actions of powerful corporations and U.S. agencies.

The ACE did issue a statement in November acknowledging historic “dispossessions of lands” as a factor being weighed, yet it is unclear whether this view will ultimately be used to build improvements into current tribal consultation policies.

2. Tribes everywhere are pressured by extractive industries.

Pipelines, mining, drilling, refining, and other extractive and industrial projects continue to try to enter tribal lands and waters around the country.

In the Pacific Northwest, the Lummi tribe recently worked to block plans for a coal-export port that posed risks to their treaty-protected lands. In the Great Lakes, the Menominee Nation hosted a Sacred Water Walk to protect cultural sites and environmental quality from the “Back Forty” sulfide mine. In the Southwest, the Navajo Nation is suing EPA over the Gold King mine’s spilling of contaminated water, including lead and arsenic, into the Animas River. And I could go on to discuss countless more cases.

For almost every tribe, this is not their first time dealing with extractive industries and hydropower projects.

The Navajo Nation was devastated by uranium mining in the middle part of the 20th century and still deals with uranium cleanup today. Historic mining and hydroelectric development in Washington and Oregon affected treaty protected habitats of fish, plants and animals for the Lummi and many other tribes, which are still dealing with the ecological impacts today.

Of course, the Standing Rock tribe itself endured losses of valuable lands due to a range of historical factors involving extraction and hydropower including U.S. support of gold prospecting and the construction of the Lake Oahe Dam.

3. The Trump administration is possibly exploring the privatization of some tribal lands.

As the Trump administration comes into power, some tribes recall comments Trump himself made years ago in relation to gaming which demonstrated both disrespect and ignorance.

Now recent stories suggest that the Trump administration — Trump has recently sold his stake in ETP — would seek to explore policies that make it easier for extraction to occur on tribal lands.

Reportedly, some of the options on the table involve privatization of tribal lands, echoing historic allotment and termination policies that sounded good from a U.S. capitalist mindset but that ultimately devastated many Native American economies through weakening tribal governmental sovereignty against the economic interests of U.S. settlers.

4. It is unclear the extent to which the #NoDAPL movement educated anyone.

The failure of U.S. public and private education and many media outlets to consistently cover indigenous histories and current issues means that potential allies of indigenous peoples do not have much background in relevant areas — everything from treaty rights to indigenous activism, to federal Indian law (and its limits), to indigenous religious and cultural values.

While many allies are able to send money or show up for what they understand as “direct action,” they do not know how they can advocate for indigenous peoples beyond the rare highly public issues. They do not, for example, seek to regularly pressure their political leaders to reform the government’s duty to consult with tribes before construction projects. Or they are not aware of indigenous peoples facing similar struggles to that of Standing Rock who are living right next door to them.

5. U.S. colonialism is not over.

All the points I have made are really just by-products of one key point: DAPL is not over because many people in the United States assume that it is acceptable to keep pushing tribes to make sacrifices for U.S.-endorsed business interests, whether these interests profit individuals or are portrayed as being in the national interest.

From an indigenous perspective, it is deeply frustrating to witness, generation after generation, a U.S. parasitism that continues to build the U.S. economy through infringing more and more on indigenous lands and waters, as we see from many ongoing energy and water projects detailed above.

Why is the underlying assumption always that indigenous peoples must sacrifice their cultures, economies and political self-determination for the sake of the aspirations of businesses and U.S. national interests? This question poses a significant problem for the ethics of DAPL even if it were absolutely certain that the pipeline is far safer, in many respects, than oil transport by rail.

It remains possible that the two-year-long Environmental Impact Assessment will not ultimately respect the involvement of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. Or perhaps ETP will just keep building the pipeline and deal with the financial or legal consequences.

Regardless, tribes everywhere, this year and into the future, will face broken treaty rights, inadequate consultation, uphill battles against rich companies, and federal and state agencies whose goals and procedures ultimately do not take to heart indigenous values, histories and sovereignty.

![]()

Kyle Powys Whyte is the Timnick Chair in the Humanities and an associate professor of Philosophy and Community Sustainability at Michigan State University.

Shares