In my early twenties, fresh from journalism school, I moved to Louisville, Kentucky, home of the greatest two minutes in sports and the most recognized man on the planet. On the first Saturday in May 1999, both came together for me when a local magazine sent me to Churchill Downs to report on the Kentucky Derby from the expensive seats. Muhammad Ali was there.

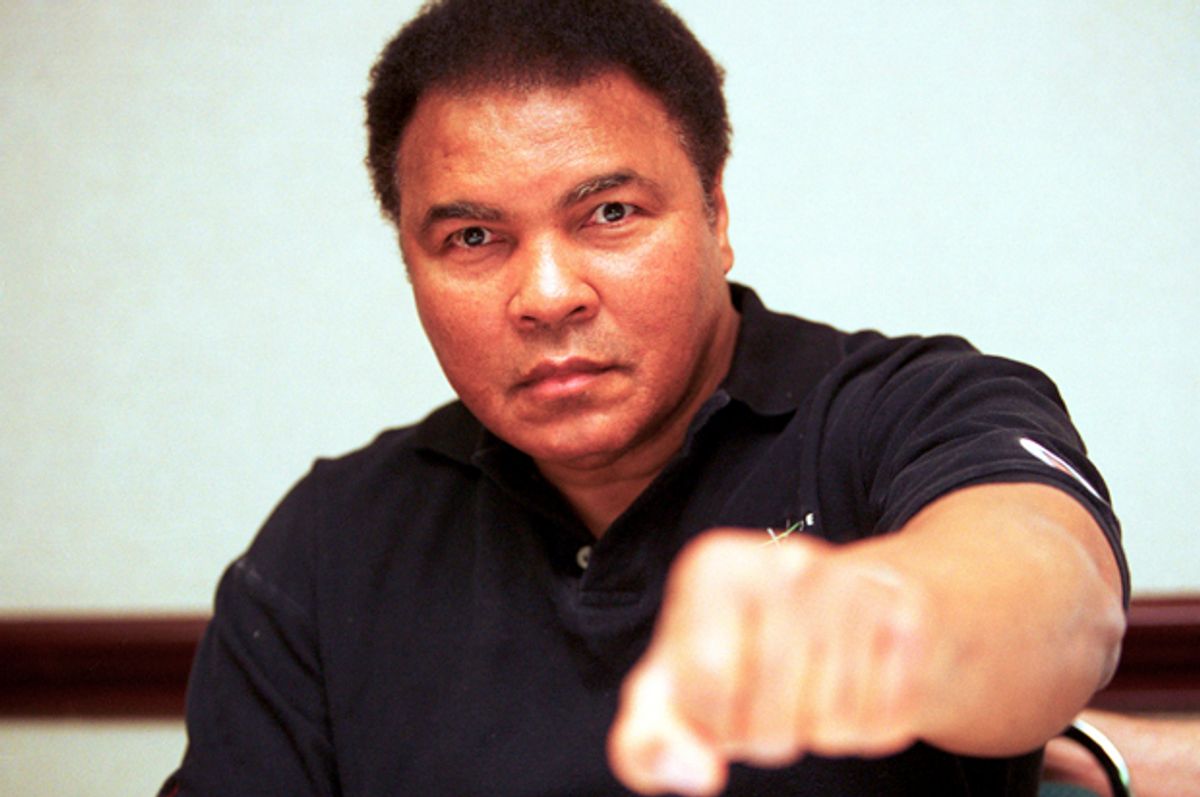

Ali, who would have turned 75 on Tuesday, stood tall on his feet that day on Millionaire’s Row, receiving a long line of fans. Parkinson’s had nearly stilled him by then; his once dazzling physical presence had modulated into a quiet glow. But oh, what a glow. I joined the queue — partly for the sake of my story, but mostly because I could not resist his pull. Only then did it occur to me to wonder what I would say to the man. I had no personal connection.

Except this: As a small child in rural Kansas, I often sat with my dad in his green recliner in front of the TV, cheering Ali in his prime. Dad loved the fights, but I watched for the arguments: the Louisville Lip vs. Howard Cosell. I was too young to understand why they were going at it, but I knew even then that Ali possessed a quality I would later learn to call charisma, a brash certainty that excited and dismayed me. "I am the Greatest," he said. His mind all speed and surprise, same as his body. By then Ali had already won the world heavyweight title only to have it stripped from him, the price of saying no to the United States Army. He would not "drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negros in Louisville were treated like dogs." Those were his words.

By the time I was 4, I had grown too big to share my father’s recliner. Dad, a pilot, took a commuter job selling Aerostar airplanes. Most nights he returned home past my bedtime; in my mind, he became a visitor in our house. He still wouldn’t miss a fight, but my own interest waned, the sport too brutal. When Ali reclaimed the heavyweight title with the Rumble in the Jungle in 1974, I was 7 years old, my world all horses and "Happy Days." For me, Ali had morphed into a pitchman: “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. The great smell of Brut and the punch of Ali.” By the time he recaptured the title the second time, my parents had divorced. When he retired from the ring a few years later, I didn’t much notice.

On Millionaire’s Row, the line of fans moved slowly. When my turn came, Ali looked at me, his face nearly mask-like because of the disease. I suppose I felt sorry for him, so reduced (I thought) from the days when Ali meant the Greatest. Stumblingly, I offered my admiration, but I lacked the words to explain how he’d riveted me as I watched with my dad. The moment slipped away even as it unfolded.

Then the champ did something that mystified and slightly alarmed me. He began bending toward me as I spoke, an incremental tilt from the waist as if he were executing a formal bow a millimeter at a time. His face offered no clue about the purpose of this gesture. I spoke, he bent, till I lost track of what I was saying. Only when his cheek presented itself inches from my face and he pursed his mouth did I get the message. So I did what he was asking. I shut up and kissed Muhammad Ali.

My lips left a rose-colored smear on his soft brown cheek. His eyes slid past mine, and he handed me a leaflet and tapped the green paper with an unsteady forefinger. With effort he whispered, “There’s truth.” I walked away half dazed clutching a flier about the Qur’an, his gift to me.

A few years later, I got a job at Spalding University in downtown Louisville. Across the street from my office stands the building that once housed the Columbia Gym, where young Cassius Clay first learned to box. As a teenager, he worked in the Spalding library, cleaning the building and charming the nuns. Proximity rekindled my interest. My husband and I watched the documentary "When We Were Kings" and, later, Will Smith’s film "Ali." We went to the Muhammad Ali Center, a six-story compendium of his fights, his principles and his humanitarian work. Like the rest of my adopted hometown, I grew to love the man: the brawler turned peacemaker, the fighter who sacrificed his livelihood because he refused an unjust fight. You couldn’t have invented him, and you can’t imagine the world without him. He was the Greatest of All Time until Parkinson’s showed up to remind him that only God is the greatest. That was the meaning he made of his disease.

Dad and I never recovered the connection we’d had in the days of the green recliner. There had been no falling out, just a steady drift apart, and I’m not sure I even told him about the kiss on Millionaire’s Row. In the months before he died in 2008, I visited Dad in California frequently: penance, maybe, for the distance we never bridged.

On what would turn out to be my final visit, I took him to the airport in Van Nuys one afternoon to watch small planes take off and land. The cancer and its horrid treatments had punched holes in his mind by then: he’d lost memories, names. Yet amid the familiar sounds of engines revving and winding down, we talked about his love of flying, about our family before the divorce, about the long-ago days when we watched the fights together. That tattered conversation became our goodbye, our way of saying out loud that once, when I was very young, we two had been close. Forgetting for a minute that he was dying, he told me, "If I had a bigger airplane, I'd teach you how to fly."

Dad died a few weeks later. At the small service, I said some words: an attempt, I guess, to explain things to myself.

And that was all.

Until this. Early on a Friday morning this past June, I put on my best black dress and helped carry Spalding’s 13 academic banners to the deserted corner of Fourth and Broadway. My colleagues and I hung the blue-and-gold flags on brass standards, spaced them precisely on the sidewalk with the help of a measuring tape, and waited for Muhammad Ali’s funeral procession.

The morning waxed, then waned. People set up lawn chairs. The crowd grew thick, the sidewalk a hive. Men sold Ali T-shirts out of cardboard boxes. Sometime past noon, helicopters appeared at a distance, tracing the procession’s route, and I stepped away from the academic banners and into the crowd.

When the choppers reached us we spilled into the street, pumping our fists, shouting "A-li! A-li!" Police cars nosed up, spinning red and blue, and we stepped back just enough to allow their passage single file. Behind the cruisers, black limousines, the gleaming hearse strewn with yellow and orange flowers. The men and women in the cortege turned their faces upon us, lit with joy as we bore them forward on the current of our cheers. Will Smith hung half out of a limo and slapped hands as we chanted "A-li! A-li!" Another inch and I would have touched him, but what did it matter when I had kissed the real Muhammad Ali? Somehow I high-fived the imam who later that afternoon would conduct the funeral service, and as the limos rolled past, Ali’s daughter Laila came into view, a boxer like her dad, beautiful in her white dress, her face reflecting our love.

After the last car passed, I walked the two blocks back to my office and watched the rest of the procession on a live video stream. I watched for myself and for my dad. At the entrance gates to Cave Hill Cemetery, the shining limousines parted the throng and glided over a thick carpet of rose petals, red and pink, as the crowd chanted "A-li! A-li!" It meant good-bye but it sounded like gratitude. Sounded, to my ears, like the opposite of regret.

Shares