Aware of the fact that Donald Trump's Electoral College victory was made possible by at least a modest number of Democratic-leaning voters crossing party lines, congressional Democrats appear to be pursuing an intriguing strategy: They're trying to force the president to choose between the people who elected him and the political party he nominally leads.

Trump is the highest-ranking Republican in Washington. But the new president's lack of interest in the details of policymaking mean that he's outsourcing a lot of it to the congressional GOP. That's dangerous for Trump's public approval ratings because conservative elites generally favor economic policies that are likely to be unpopular with the blue-collar workers who got him elected.

In his inaugural address, as in his speech at the Republican National Convention last summer, Trump put on a mantle of populism, claiming that "the forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer."

Throughout his campaign and during his transition period as president-elect, Trump also spoke of his desire to replace the Affordable Care Act with "something terrific" that would include "insurance for everybody." In an interview with ABC News after he took office, Trump said that "millions of people will be happy" with his replacement for Obamacare.

Nor is Trump the only person in the administration to openly talk about spending more money, rather than less. Stephen K. Bannon, who formerly ran Breitbart News and now serves as the president's top strategist, has spoken of his desire for increased domestic spending. "I'm the guy pushing a trillion-dollar infrastructure plan," he boasted to The Hollywood Reporter in November.

These deviations from standard conservative economic orthodoxy were a huge part of what made Trump so unpopular with right-leaning elites. Many of them were fond of calling him a liberal, in the futile hope that doing so might lead Republican primary voters to reject him.

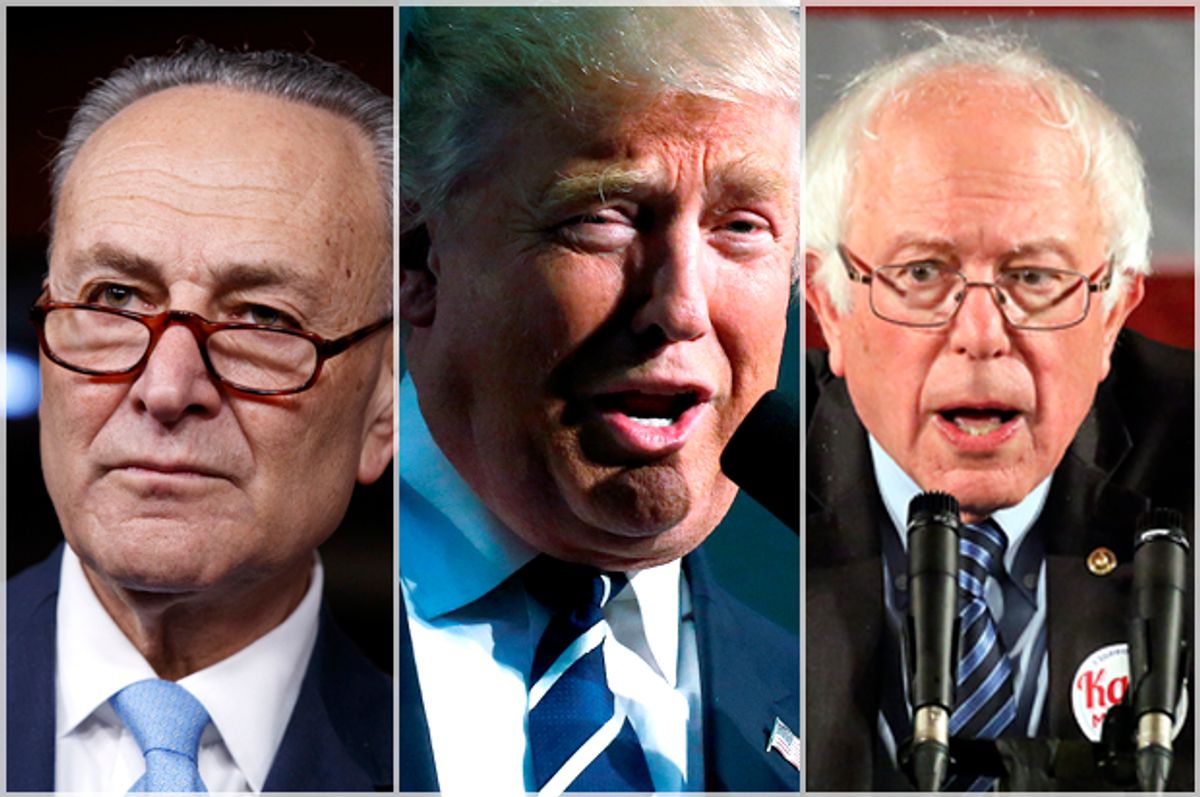

Thus far, some of Trump's actions have hewed to his populist rhetoric. His withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade treaty was praised by progressive darling Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt. Likewise, his choice to meet with members of several construction-oriented labor unions during his first Monday on the job — a courtesy many of them never received from former president Barack Obama — and his early and public embrace of the Keystone XL and Dakota oil pipelines haven't gone unnoticed by blue-collar America.

In a statement, a consortium of builders' unions praised Trump in fulsome terms for his Wednesday executive order on the pipelines:

"Today, President Donald J. Trump gave continued hope to thousands of skilled craft construction professionals in America's heartland for whom the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipeline projects have been an economic lifeline," said the leaders of the North America's Building Trades Unions federation.

Still, not all of Trump's early policy endeavors have backed up his populist promises. On Medicaid, as Salon's Simon Maloy has noted, the president has decided to go along with congressional Republicans' desires to move the program to a block grant funding structure, which would permit Republican-dominated states to reduce funding for the low-income medical care program. Trump officials have also indicated a willingness to go along with GOP plans to remove subsidies for private insurance companies that help to offset the costs they incur by being forced to guarantee coverage for all.

Trump's savvy relationship with organized labor has led to concern among Democrats that his efforts to peel off a significant portion of the union strength that is critical to the liberal coalition will continue to pay off.

In the November election, Trump performed better among voters in union households than any Republican presidential candidate since Ronald Reagan's across-the-board landslide victory in 1984.

Faced with Trump's triangulation efforts on spending and populism, senior congressional Democrats unveiled on Tuesday a $1 trillion infrastructure spending plan of their own. Unlike Trump's current rather vague proposal, it relies on direct federal spending instead of tax credits. Senate Democrats backing it claim it would create 15 million jobs over the next 10 years.

By creating their own stimulus package that is even larger than the one that Trump is currently aiming for, senior Democrats, led by Sen. Charles Schumer of New York, are hoping to drive a wedge between the budget hawks who dominate the Republican Congress and the disgruntled Democratic voters who rejected Hillary Clinton as an out-of-touch globalist.

An anonymous senior Senate staffer spelled out the strategy explicitly to Atlantic writer Michelle Cottle:

“We are presenting a choice to the president,” said the senior Senate aide. If he pursues issues that align with Democratic priorities, “he will find Democrats eager to work with him.” This will, however, require Trump to “buck the Republicans in Congress,” stressed the aide. Democrats’ selective cooperation is not aimed at “finding middle ground” with GOP members, the aide clarified, but about Trump’s “upending decades of Republican orthodoxy” and “going around congressional Republicans” on particular issues. The goal: deny the majority legislative wins while positioning Democrats as the party that can work with Trump to get stuff done.

The strategy is not without its critics. Liberal commentator Jonathan Chait blasted the Democratic effort as "delusional" on the day that it was announced. According to Chait, the proposal is naive for assuming that Trump would not be willing to spend the money and that it ignores how past Republican presidents have had no problem with deficit and stimulus spending.

Chait also warned Democrats that helping Trump achieve a bipartisan victory with an infrastructure bill would also confer legitimacy on him which would only benefit Republicans:

In theory, it might make sense for the public to conclude that Democrats are doing a better job than Republicans of helping Trump govern. In reality, that is not how they think at all. If Trump passes a bipartisan bill, it will make Trump more popular, and thus Trump’s party more popular. Democrats’ success in the next two elections will be determined by Trump’s approval ratings. The lower his ratings, the better Democrats will do. Voters are not going to reward Democrats for proving they can get stuff done with Trump.

That's certainly one possible outcome. But there's some evidence to suggest that Democratic voters have dramatically different attitudes toward political compromise than the GOP base does.

Put simply, Democratic voters want their politicians to compromise and get things done. Republican voters are much less inclined toward working together. Thus, Democrats are not likely to benefit from frequent threats of government shutdowns the way that Republicans did during the Obama years.

This disparity has existed for some time. Following the 2000 recount controversy, 64 percent of Democrats told The Los Angeles Times that they supported George W. Bush as the president. In a June 2001 CBS/New York Times survey, Democrats were 10 points more likely than Republicans to favor cooperation between Bush and congressional Democrats.

In 1998, a Gallup survey found that just 49 percent of self-identified Republican participants wanted their party to elect leaders who would be more willing to compromise with then-president Bill Clinton. At the same time, 50 percent of GOP respondents said they wanted their party to pursue "more conservative" policies.

The partisan split over compromise only widened during the Obama era. Seven years after Republicans made obstruction their primary governing strategy, Democratic voters were still seeking to work together. A 2015 NBC/Wall Street Journal survey found that self-identified Democrats favored presidential candidates who wanted to "gain consensus" (60 percent of the respondents) over those who "stick to their positions" (35 percent). In contrast, slightly more Republican respondents preferred an uncompromising candidate (49 percent) over someone who sticks to positions (48 percent).

A 2014 Pew Research poll found similar results. Roughly two-thirds of the Republicans surveyed, 66 percent, wanted their congressional leaders to "stand up" to then-president Obama. Just 43 percent of the Democrats polled said they wanted Obama to "stand up" to Republicans. In 2015, an AP poll found that 62 percent of GOP respondents said they were even willing to support a government shutdown in the service of conservative principles.

The greater Democratic willingness to compromise is mostly the result of the successful efforts of conservatives to drive moderates out of the Republican Party and the post-Clinton efforts of Democrats to take them in. There likely is some sort of psycho-ideological impulse behind conservative and liberal attitudes as well. In fact, it's something that Chait himself wrote about in a 2011 article for the New Republic:

Republican voters, much more than Democrats, want their leaders to stick to principles and avoid compromise. . . . I suspect it reflects the underlying differences between conservatism and liberalism. Liberalism is an ideology that values considering every question through the side of the other fellow and not just through your own perspective.

Chait may not like it, but polling and psychology suggest that Democratic voters expect their political leaders to try to find some common ground. We're also still so far away from the 2018 midterm elections that any credibility Trump might gain from being able to claim victory on an infrastructure package isn't likely to have any staying power given how fast the news cycle moves in the age of Twitter.

Using compromise as a weapon is something that has already worked in the past for Democrats.

During the George W. Bush presidency, Democrats, led by senator Tom Daschle, didn't set brushfires in the Capitol rotunda the way that Ted Cruz did during the Obama years. But Democrats achieved great results for themselves nonetheless, winning a majority of state governorships and majorities in both the House and the Senate. Much of that had to do with the fact that Daschle and his colleagues persuaded left-leaning voters that they had tried to compromise but had been rejected by extremist Republicans.

Past is not predicate, of course, but there's plenty of evidence to suggest that if Democrats let Trump take sole ownership of an infrastructure spending bill that ends up creating even a few hundred thousand new jobs, the president's efforts to retain and expand his share of the blue-collar vote will pay off big-time. Attempting to pry Trump away from Republican orthodoxy, on the other hand, may alienate some on the Democratic left, but it makes political sense.

Shares