There is widespread agreement among political commentators that Donald Trump is a unique figure in the political history of the United States — and a uniquely dangerous one as well. David Frum recently published a chilling article in The Atlantic titled “How to Build an Autocracy,” and The Washington Post’s John McNeill suggested last year that Trump was a “semi-fascist,” according to a set of robust criteria assembled by “dozens of top historians and political scientists.”

As the comedian Jon Stewart recently said on "The Late Show With Stephen Colbert," “We have never faced this before: purposeful, vindictive chaos.”

There are many immediate reasons to be worried about a Trump presidency, from his “Muslim ban” that will almost certainly exacerbate terrorism to his normalization of bad epistemology, which has taken the form of fake news, “alternative facts” and conspiracy theories. But what about the long-term stability of American democracy? What might be the consequences of Trump’s policies for the younger generations among us? Could our democracy sink into autocracy, as some fear?

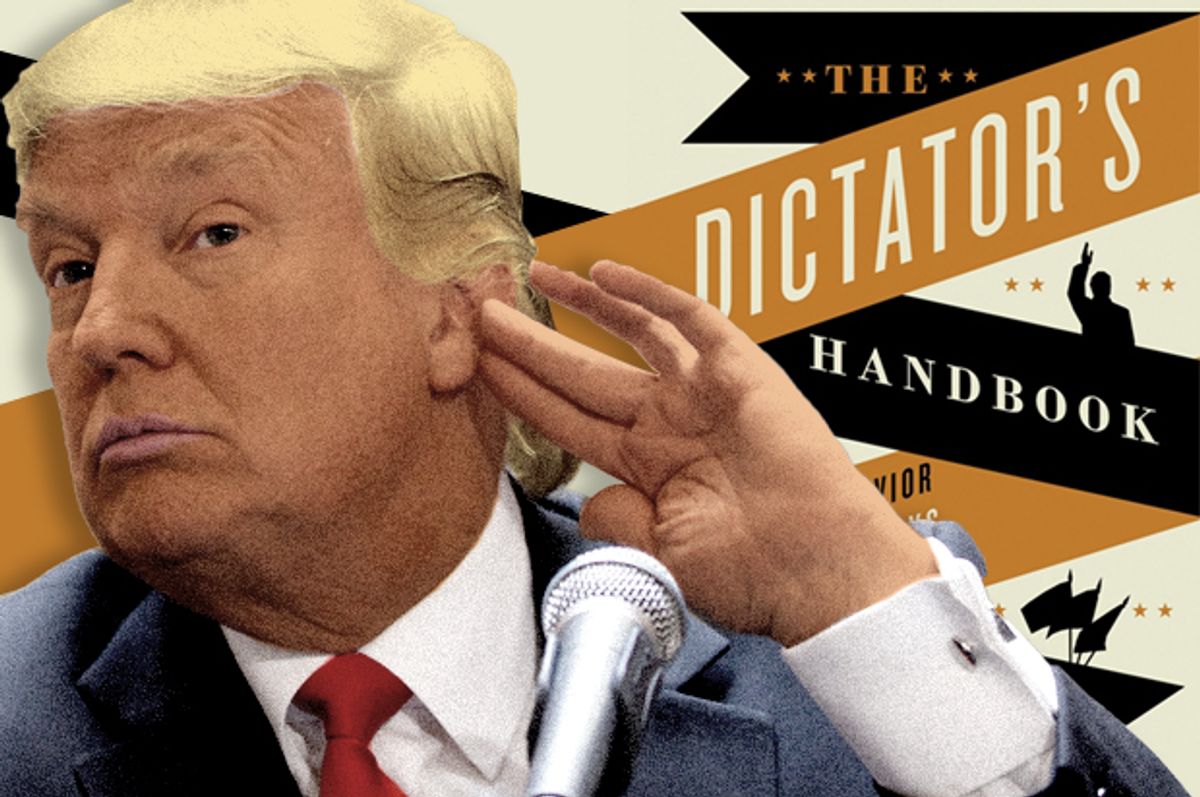

To answer these questions, I contacted Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith, professors at New York University and the co-authors of "The Dictator’s Handbook." Published in 2011 but more relevant than ever, this book offers a fascinating exploration of how people gain and sustain control over power structures like governments and corporations. For a marvelous overview of their ideas, I encourage readers to watch “The Rules for Rulers,” a video based on "The Dictator’s Handbook" that went viral last year.

I contacted Bueno de Mesquita and Smith over Skype for an engaging 38-minute chat. (This interview has been lightly edited for clarity; hyperlinks have also been added.)

What are, in your opinions, the most important differences between democracy and dictatorship?

Alastair Smith: We like to think of them as not being distinct but existing on a continuum. They actually share many features. At the top of an organization there’s a person who wants to stay at the top of the organization, and so they generate policies that get people who enable them to stay there to support them. So the difference is a degree of magnitude as to how many people you need.

To win the presidency in the U.S., you’re looking at tens of millions of voters, although the number is much smaller than you might first expect because of the Electoral College. You only really need two and a half of the seats in the marginal districts of the marginal states. But it’s still a very large number. Whereas somewhere like North Korea, we’ve had experts arguing with us about whether it’s 11 people that are really important and whether the 12th guy is really that important or not.

So for us they’re not inherently different, merely different in scale. The fundamental dimensions of politics are the same: You want to keep power and you need supporters to keep you in power; the question is how many supporters you need to do this.

What are the hallmarks of a society shifting from one to the other — let’s say, of a democracy sliding into dictatorship, which many people are concerned about today?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: The key issue is how many people the leader needs to depend on and keep happy so as not to lose power. For an autocracy becoming a democracy, it’s a question of expanding the number of people to which you’re accountable. For a democracy to become more autocratic, it’s an issue of depending on fewer people. But this is not a linear process.

If I may be a little technical: When you depend on very few people, they’re getting a lot of private benefits. As you start to expand the number of people you depend on, they’re getting fewer and fewer private benefits while society is getting more and more public benefits. Eventually the public benefits come to exceed the private benefits and even the supporters are better off than under autocracy. Once this happens, there’s no incentive to move backwards because people will be made worse off rather than better. So mature democracies don’t become authoritarian. They can oscillate a bit and become more or less democratic, but they don’t become dictatorships. Indeed, if we’re talking about a mature democracy, one where the institutions are in place, it has never happened before. This offers a little hope.

Having said that, it’s not a super-rare thing for presidents to get elected without a majority vote. In fact, it’s very common. And there are multiple instances of presidents losing the popular vote: For example, George W. Bush and Rutherford B. Hayes. But in Trump’s case, the number of critical, pivotal voters whose support made the difference between winning and losing is only about 70,000 people. If Trump can keep those 70,000 people really happy, and keep the looser part of his coalition adequately happy, then he can do a lot of what he wants.

How did you come up with the number 70,000?

Bueno de Mesquita: It’s the number of votes — specific votes — that would have to be moved for the Electoral College to have gone for Hillary Clinton rather than Donald Trump. Trump positioned his votes, in that sense, really efficiently. Abraham Lincoln, by the way, moved something like 7,000 votes. If he had not done so, Stephen Douglas would have been president! Lincoln was incredibly efficient in converting votes into victory.

In your view, how worrisome is Donald Trump’s apparent delegitimizing of the press? For example, Trump called CNN “fake news,” Steve Bannon told the media to “keep its mouth shut.” And both have repeatedly described the media as the “opposition party.” Is this a dangerous push towards a less democratic form of governance?

Smith: People tend to think of democracy as just being about free and fair elections. But democracy is about a lot more than that, at least in the way we view things. For example, Iran actually has very free and fair elections, but there are real restrictions on who can run. And there are real media restrictions as well.

What’s very important is that people have the rights of free speech and an independent media. I don’t see Trump being particularly successful at making the media be quiet. It’s worrying that he gets away with some of it. But he’s now being called out for basically living in a post-factual world where these things don’t matter. So, I’m less concerned in the long run. If Trump were to start banning newspapers and prosecuting them, that’s very much how dictators like to do things: Bankrupt newspaper owners if they print stories that they don’t like and lock up journalists. I don’t think that anybody perceives that Trump is going to do this in the near future. The press will continue to talk about Trump; indeed, you’re writing and you’re not feeling the risk of being censored.

[This is correct: My greatest fear right now is being trolled.]

Bueno de Mesquita: I think there are three pillars to an accountable government. Many of the things that people think of as being pillars, like the rule of law, follow from these three pillars. You need freedom of assembly, free speech and free press.

That is, people have to be in a position to exchange information and find out that they’re not alone in disliking what the government is doing — and to organize and coordinate to oppose the government. The two threats to the free press are a) fake news, although “noisy news” has always been prevalent, like if you were to go back to colonial times, you’d find that this was true, and b) self-censorship: When Bannon says the press should shut up, he means censor yourselves. That’s a real danger because, to put it harshly, the press is not in the business of telling the truth. The press is in the business of selling advertising space to make money. So if telling the truth turns out to be a liability, then they might begin to self-censor. That is certainly what happened in Hong Kong after the return to China.

There was a little bit of a negative sign [this week] that made me concerned: President Trump made the selection of the Supreme Court justice into a game show by bringing in candidates rather than the one person he’s going to designate and then designating one — essentially humiliating the other. In my view, if I controlled a network or newspaper, my coverage would have been “President Trump has nominated Neil Gorsuch for the Supreme Court.” I would not have given live television coverage of the farce as all the networks did because they were simply feeding Trump publicity that was not news. So I found that a little worrisome.

But the bigger threat is if there’s a loss of freedom of assembly. So far this freedom is working well — enough people have been actively protesting. For example, earlier this week Trump was essentially compelled to stay in the White House rather than go to Milwaukee and face opposition. That’s what has to happen: People have to be active in making known that they are concerned.

To paraphrase Barry Goldwater from a very long time ago, vigilance is the price of freedom. If people just sit back and say, “Well, democracies don’t become autocracies, so I don’t really have to bother.” People have to be using the freedom of assembly, using the free press and free speech to make it costly for members of Congress to go along with what the president wants when they believe it’s a mistake. Members of Congress have to believe that it threatens their re-election not to be a constraint on Trump.

So what worries you most about the Trump administration?

Smith: I’m more worried about the policies that he could implement, rather than deep-seated, long-term institutional changes. The courts are independent and already we’ve seen them rule that some of Trump’s policies are illegal. In the long run, of course, Trump can close down courts. A dictator closes down courts and gets rid of the independent judiciary. But that process takes a while. For a very long time in Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe was actually held in check precisely because the courts were independent. It took him a very long time to erode that power. So Trump is not in a position to completely erode the courts. He's going to shift the policy focus of the Supreme Court, which worries a lot of people: It’s going to have a much more conservative outlook. But he’s not fundamentally going to take away courts where people can get reasonably independent rulings.

In terms of changing electoral law, again that’s going to be difficult. The Republicans like to do this. They love to gerrymander, and so do the Democrats, although [Republicans] seem to have the upper hand right now. They also like to restrict voter access, for example, to reduce the number of people who are going to vote against them. But at the end of the day, are the Republicans in Congress going to go along with Trump undermining the democratic system? That seems unlikely to be in their interest. Let’s have “King Trump.” This is not in the interest, I think, of the Republicans in Congress.

Bueno de Mesquita: If I can go back to Alastair’s first answer [above]. We prefer to think of governance forms as a continuum, not a dichotomy. We argue forcefully in "The Dictator’s Handbook" that all political leaders, if unconstrained, would rather be dictators — all, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, George Washington, Abraham Lincoln. So the constraints are exactly as Alastair has pointed out: these deep institutions that are very hard and slow to erode.

I’m more concerned about the danger that President Trump puts us in with respect to foreign affairs than I am about the danger that he puts us in domestically. The president has much more latitude in foreign affairs than he does in domestic politics, and that is where his inclinations make me fearful.

Speaking of the courts, how plausible is it that the federal government could simply ignore the courts — a situation that apparently happened following a federal court order on Trump’s travel and immigration ban?

Bueno de Mesquita: Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus in order to pursue his policies at the beginning of his term. He met the chief justice of the Supreme Court on the street at the time, and the chief justice told Lincoln that he was acting unconstitutionally. And Lincoln said, “Well, that may be so, but you don’t have a session for another however many months. And in those months I’m going to save the Union.” So presidents can thwart the courts for a while but not indefinitely. But it’s worth noting that thwarting the courts is the fast track to impeachment.

This segues to my next question: How likely is impeachment in the next four years? My understanding is that an emoluments clause violation is sufficient for impeaching Trump. The means are there. What’s needed is the political motivation.

Smith: I’m not going to weigh in on the legal issues because I’m not a lawyer. This is not where our expertise lies. But impeachment has always been very much a “political will” issue. It’s costly for Congress to impeach a president, so they don’t want to do it all the time. But the president is constrained: He can only push Congress so far before it will remove him from office.

Bueno de Mesquita: I would add that as a matter of historical record the only times that a president has faced a serious threat of impeachment — or serious talk of impeachment — is when he had a divided government — that is, when the Congress was of a different party from the president. Trump is an interesting case because it’s not obvious that he’s a Republican. He’s certainly not a Democrat. Rather, he’s something else. So the divided government may or may not be in place.

My own personal opinion — again, not being a lawyer — is that Trump is much more likely in the next four years to be removed from office under the 25th Amendment, whereby the president is deemed to be incapacitated. I think if he persists in using, as they have called it, “alternative facts,” when the evidence does not support what he is saying, and he nevertheless tries to shape policy on that basis, there’s going to be a point at which there will be a judgment that he is not mentally stable.

Any final thoughts about the current trajectory of human civilization?

Bueno de Mesquita: The implication of our theorizing is that, loosely speaking, democratic government is the more dominant long-term form, but it’s not the unique form. It is not in equilibrium to have no dictatorships. Part of the reason is that while democratic leaders say they want to promote democracy around the world, in fact they don’t. What they want instead is foreign governments that, at the margin, will be compliant with policies that the democratic leaders’ constituents want back home. It’s very hard for a democratic leader in another country to comply with what you want if their voters don’t agree with you. But it’s very easy for autocrats to comply because all you have do is to give them what they need to stay in power, which is money to bribe their small group of cronies. And for you to stay in power, you need, at the margin, policy compliance. So there’s always a place for dictatorship.

Shares