Jill Stein really, really wants you to know that she’s not responsible for President Donald Trump. I had a chance to put that case to the Green Party’s 2016 presidential nominee when she visited Salon’s New York office on Friday, and she was more than ready for the accusation. Stein has a point — at least up to a point.

Her comeback is sensible enough: The math doesn’t work. To make the case that Stein played a definitive spoiler role in the 2016 presidential election, you have to assume that nearly all her voters (or at least nearly all of them in the key Midwestern states won by Trump) would have yanked the lever for Hillary Clinton if Stein hadn’t been on the ballot. No one can prove or disprove what might have happened in an alternate universe, but Stein is correct to say that isn’t a coherent or logical assumption. She says that polls of Green voters suggest that most of them would simply have stayed home, some would have voted for Trump or Libertarian nominee Gary Johnson, and fewer than one in three would have voted for Clinton. That almost certainly would not have been enough to alter the outcome.

So I concur that it’s not fair to point the finger at Stein and the Greens and say “You ruined everything!” She’s right to observe that the number of Democrats who didn’t bother to show up at all, or who crossed party lines to vote for Trump, vastly exceeds the number of potential Clinton voters who went Green instead. She’s also right that the Democratic Party’s default position after every electoral setback is to blame renegade leftists on the margins rather than confronting the consequences of several decades’ worth of rootless, rudderless ideological drift. To consider the “Ralph Nader factor” in isolation — as if it had no political causes and no historical context, and as if it could have been wished away — was not entirely fair in 2000 (when the case for it was a lot stronger), and is even less so in 2016.

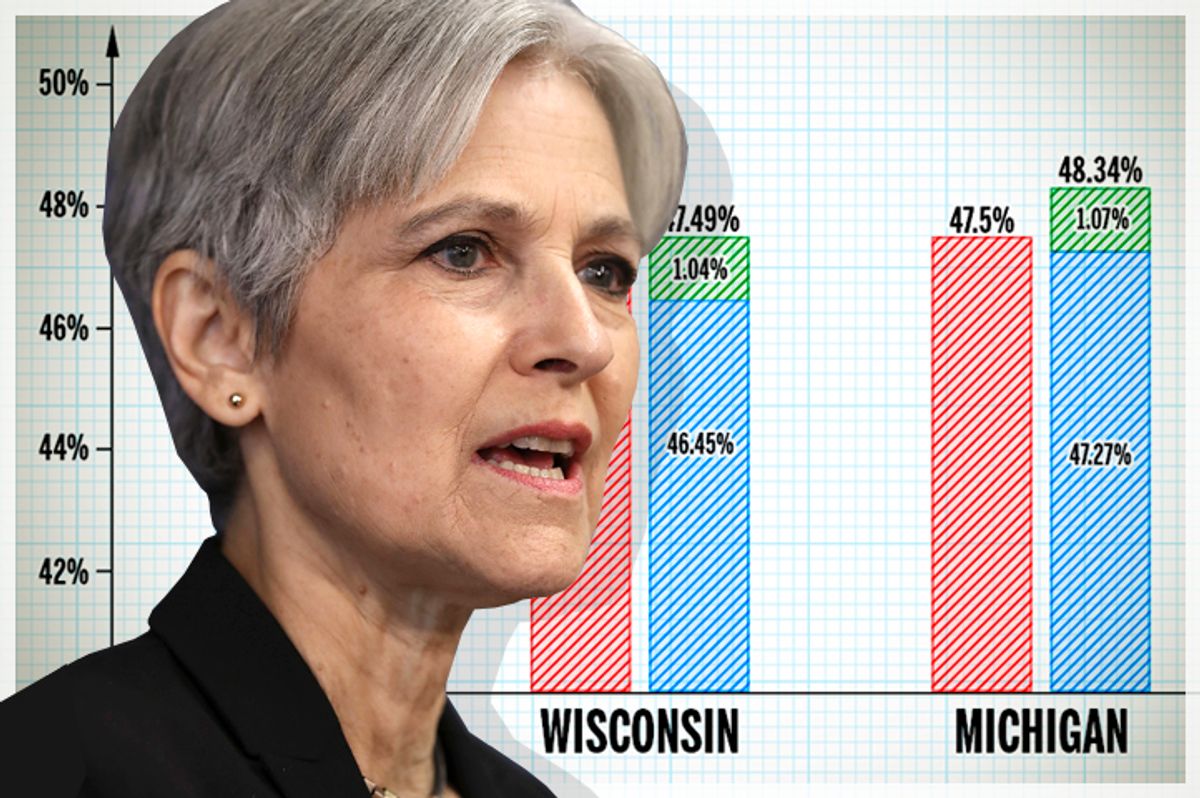

But even the fact that Stein’s vote total was too small to make much difference, and that the Democrats’ major institutional and ideological problems lie elsewhere, speaks to the fundamental weakness of her position. On one hand, the Green Party’s optics are terrible, as we say these days. There’s no way around the fact that Stein’s modest vote totals in each of the three fateful states that put Trump over the top — Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — exceeded the razor-thin margins between Trump and Clinton.

As I’ve already said, I’m inclined to agree with Stein that only Democratic magical thinking can make her into the unique villain of the story. But the P.R. damage to Stein and the Greens has been extensive, as it was in 2000, and she grew unmistakably defensive about that during our conversation. This election was an unlikely statistical outlier, decided by a pileup of marginal factors acting in concert: FBI director James Comey’s letter to Congress, the alleged Russian hack and resulting WikiLeaks dump, the Clinton campaign’s arrogance and ineptitude, and so on. In that context of unknowable murk, interpretations and impressions outweigh arithmetic. For many liberals and progressives Stein’s 1.5 million votes (just over 1 percent of the total) will always be a troubling unsolved variable in the larger equation of what might have been.

On the other hand — and this part is a lot more important, and not unrelated — the entire political project of the Green Party looks like an unmitigated failure. Stein got only half as many votes as Ralph Nader did in 2000 (with a smaller electorate), and only one-third as many votes as Johnson, the former New Mexico governor who had apparently never heard of Aleppo.

Her attempt to present herself as the authentic voice of a majoritarian progressive politics, and a crusader for electoral reform and voter justice, now seems almost desperate. Stein’s sincerity and conviction are without doubt. She has been involved in left politics since the late 1960s, and you can’t spend any time with her and accuse her of being cynical or pursuing narrow self-interest.

But especially now, with a vigorous internal battle roiling the Democratic Party in the wake of the Bernie Sanders campaign — Stein and Sanders are old friends and longtime comrades — she finds herself with almost no platform left to stand on. Her third-party quest was always an extreme long shot, and Gary Johnson’s success suggests that if a viable third force ever emerges in American politics, it will not be hers. Stein strikes me as a Puritan preacher whose congregation has gradually lost interest in the gospel and drifted away to other things.

Politics is always a matter of finding the right balance between principle and pragmatism, as Machiavelli, Lincoln and Lenin would all have agreed. Stein, to my ears, has no sense of that balance. On a personal and philosophical level, I agree with many of her criticisms of the Democratic Party, which over the course of the last half-century has made a devil’s bargain with Big Capital and backed away from any clear commitment to economic justice. But my personal convictions, or Jill Stein’s, will not be enough to retrieve our failing democracy from the abyss, or to address the national crisis posed by Donald Trump’s presidency.

Stein appeared to have her own micro-Aleppo moment when I raised the example of the French presidential election of 2002, when that nation’s entire left had to swallow its pride and support incumbent Jacques Chirac, a center-right Establishment aristocrat, against the neofascist Jean-Marie Le Pen. (Whose daughter, Marine Le Pen, has now positioned herself far more artfully as the French translation of Trump.) I'm not convinced she had any idea what I was talking about.

Such “emergency coalitions,” to be sure are not sufficient in themselves and do not solve underlying social and political problems. The Democratic Party has functioned as a permanent emergency coalition for far too long, and it hasn't been working. In a sense that is Jill Stein's point. Maybe we always need gadflies and outsiders like her needling us to do the right thing, even when doing the right thing seems flat-out impossible and we're simply trying to save the country from sliding into autocracy. But when I asked Stein whether she really sees no difference between pressuring President Trump from the left or pressuring a hypothetical President Hillary Clinton, she ducked the question.

Shares