Over the past few days, the national climate has grown increasingly tense over the issue of “sanctuary” cities and states. Local communities, including some college and university campuses, have pledged to shield undocumented children and adults from President Donald Trump’s proposals for deportation. Municipalities and campuses remain steadfast even in the face of the president’s threats to withhold federal funding from these communities.

This opposition between federal authorities and local communities is hardly new. As a scholar of slavery and emancipation, I have studied the long history of African-American communities and how they offered sanctuary or protection to the most vulnerable among them.

In particular, I have looked at how in the 19th century, before the abolition of slavery in the United States, free black people openly defied the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 that sanctioned slavery over the human rights of enslaved people.

The law that supported rights to slaves

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 built on provisions in the Constitution and a 1793 law that barred slaves from escaping from a state where slavery was legal to one where it had been banned.

While the Constitution mainly called for the return of runaway slaves, the 1850 law vastly expanded the authority of federal law enforcement officials. The law criminalized helping or harboring a runaway slave and denied the accused person the right to offer testimony in her or his own defense.

The 1850 law confirmed what generations of enslaved African-Americans knew too well: They existed as property, not persons, in the eyes of the law.

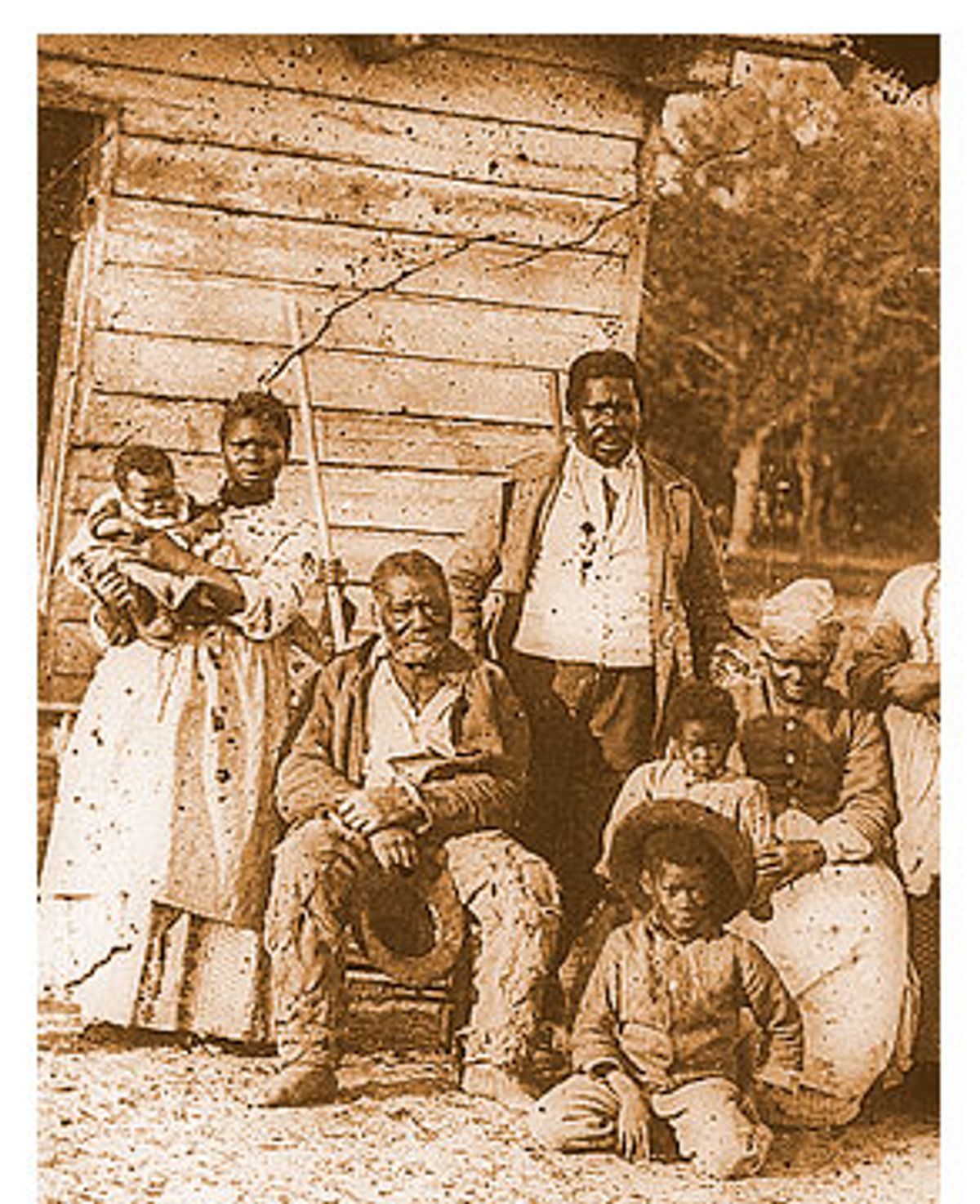

Enslaved women and men could not enter legal marriages because slaveholders claimed their bodies, time, movement and even reproductive capacity. Law and custom dictated that enslaved women gave birth to enslaved children.

Constant threat of enslavement

Freedom was always precarious for black Americans who stood on the legal margins of society. Blackness and enslavement were so firmly connected in antebellum America that to be free and black was to exist as a civic anomaly.

Free black people were recognized as citizens, though with limited rights, in the states in which they lived. Their standing as citizens of the nation remained ambiguous until after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery in the United States.

The threat of enslavement stalked many free black people. Solomon Northup, for example, was a free man who lived in upstate New York; in 1841 he was abducted and sold into slavery in Louisiana. The 1850 law made it worse. Those who had seized their freedom by running away became more vulnerable to kidnapping and enslavement.

Slaveholders advertised widely for the return of their property – the runaway slaves – and often hired men to track and capture fugitives. Newspaper reports and broadsides announced the arrival of slave catchers, warning free black people to remain vigilant especially in their interactions with the police.

On Nov. 1, 1850, the Liberator, the Boston anti-slavery newspaper published by William Lloyd Garrison, a radical white abolitionist, alerted local residents to the presence of “two prowling villains.” It said that the two slave catchers had come to Boston from Macon, Georgia, with the aim of capturing William and Ellen Craft, a runaway slave couple, “under the infernal Fugitive Slave Bill, and carrying them back to the hell of Slavery.”

Prompted to action by the Crafts’ plight, Boston’s black community gathered to plan their opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law. They adopted a set of resolutions, including a pledge “to resist oppression” and any attacks on their freedom.

Escaping bondage

Many prominent black activists gained their freedom by running away. Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs are among the best-known fugitive slaves. After liberating themselves, they continued to challenge the laws and customs that stripped black people of their freedom.

After the 1850 law was enacted, many black people set their sights on Canada, convinced they could find safety only outside of the United States. Harriet Tubman was among them. She shepherded runaways from Maryland through New York and Pennsylvania to Canada, where slavery had been abolished in 1834.

Frederick Douglass, perhaps the most widely known self-liberated slave, also left the United States to safeguard his freedom. Douglass had escaped from bondage in Maryland in 1838 and then traveled to England and Ireland.

The 1845 publication of his “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, Written by Himself” placed him in danger of being captured. Douglass returned to the U.S. in 1847 only after his English supporters negotiated with his owner to purchase his freedom.

Experiences of escape and exile prompted free black women and men to lament America’s denial of their humanity but also invigorated their determination to bring slavery to an end.

Fighting for freedom

In the wake of the 1850 law, many black people openly engaged in physical confrontations with law enforcement. Tubman, for example, fought the arrest and detainment of accused fugitives.

Almost immediately after the 1850 law was enacted, Frederick Douglass quickly organized a mass gathering in protest. In September 1850, hundreds of black and white opponents of slavery gathered in Cazenovia, New York to hear Douglass and other prominent abolitionists, some of them former slaves, speak out against the law.

In his published summary of the Cazenovia meeting, Douglass charged, “slave laws should be held in perfect contempt.” He also maintained that enslaved people should defy the laws of slavery and liberate themselves by escaping from their owners whenever they could.

In short, Douglass called on free people, black and white, as well as enslaved people to defy state and federal laws that protected slavery.

African-American history is American history. Black people’s lives, their words and actions, including their commitment to defying the laws of slavery, helped define the meanings of freedom and citizenship in the United States.

![]()

Barbara Krauthamer, Associate Professor of History, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Shares