In the '80s and '90s, New Order was one of the most innovative alternative bands around. Formed from the ashes of Joy Division — a Manchester, England, post-punk act whose career was tragically cut short by the 1980 suicide of frontman Ian Curtis — New Order melded cutting-edge electronics with meticulous songwriting and sonic flourishes. Bernard Sumner's keening vocals and Peter Hook's oceanic bass undulations served as mellifluous (and melancholy) counterpoints to drummer Stephen Morris' precise rhythmic backbone and Gillian Gilbert's icy keyboards.

Over time, however, friction built up within New Order due to these opposing musical forces (as well as combustible personalities). Hook left the group in 2007, and the rest of the band continued on without him. However, a funny thing happened to Hook in the ensuing decade: He eventually found a second career as a respected author. In fact, his second book, 2012's "Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division," even made the New York Times Best Sellers list.

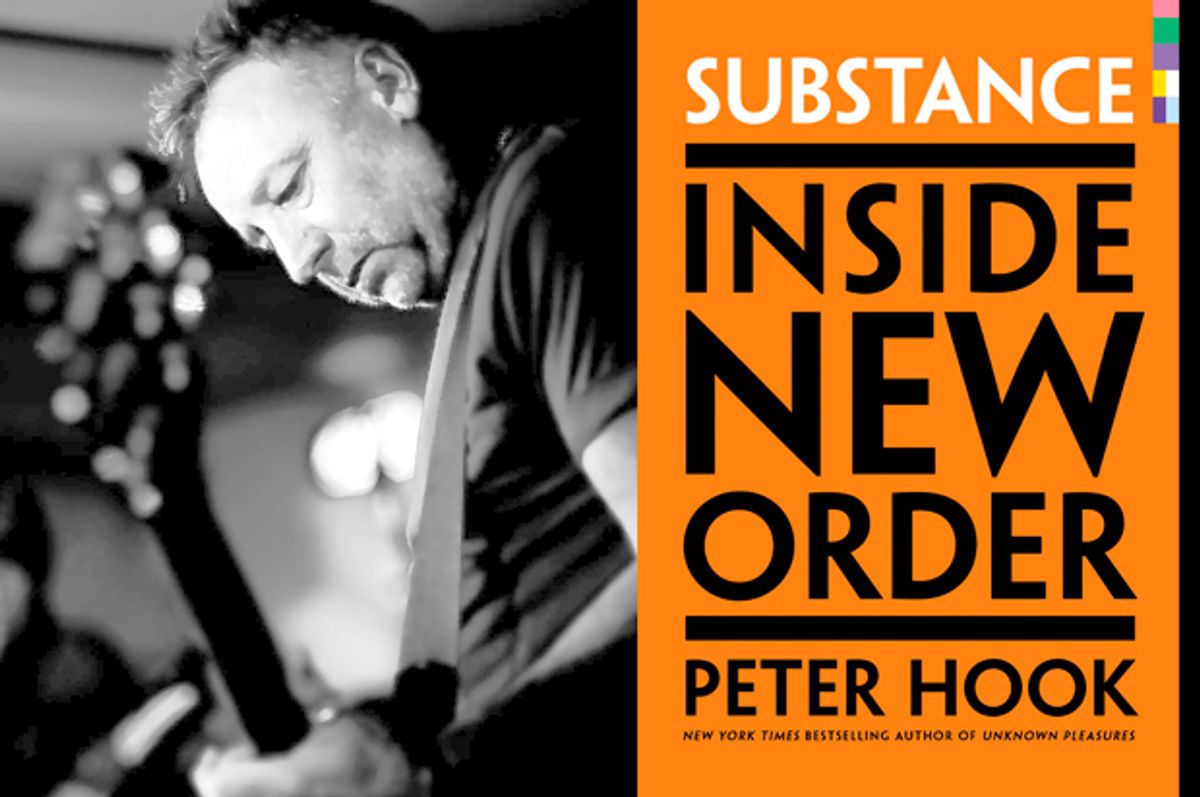

Hook's latest opus is "Substance: Inside New Order," a thoroughly entertaining 750-page book detailing the band's rise, internal turmoil and eventual permanent schism. The narrative contains no shortage of drama and debauchery; Hook is open about his once-hearty appetite for cocaine and booze, as well as the band's fractured internal dynamics, and he isn't afraid to call out his own bad behavior. However, "Substance" is also full of "geek alerts" — asides about everything from musical gear to music industry business practices — and amusing anecdotes, like the time members of New Order fought with members of the Clash over free hors d'oeuvres at a hotel bar or the day Hook encountered Bruce Springsteen haggling over the price of vintage cowboy boots at an L.A. store.

The jovial musician is now long sober and flourishing with his new band, Peter Hook and the Light, which has spent the last few years on the road playing Joy Division and New Order albums in full. Despite fighting off a cold, Hook was in a quippy mood while speaking to Salon via phone from England.

[This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.]

On the last page, you wrote that you agonized over every word of the book. Why?

I think the contrast in our lifestyles, especially with our image, was tricky, shall we say. You don’t want to kill the myth. But it was quite an odd situation to be in. Music in particular is a little bit of a pantomime. You have pantomimes in America, don’t you?

Yes.

Farce. [Laughs]

That’s another good word for it.

There was this reluctance to blow the myth. It was made easier for me at the start by the others treating me so badly with the reformation. That made it quite easy to want to get your own bat. And Bernard [Sumner] in his book [2014's "Chapter and Verse: New Order, Joy Division and Me"] certainly held no punches back about what he thought of me.

There was the indication that you wanted to get the story straight and put out the realistic story.

The thing is, we played up to the myth for so long. You do guard it, I suppose, and that was my reluctance, was really exposing [to] the world [that] New Order weren't the enigmatic, cryptic myth. They were just another bunch of lads out for a good time.

You once told Rolling Stone that a New Order book would be the "indie Mötley Crüe." As I was reading "Substance," I thought “Yeah, that’s about right.”

[Laughs] I did get paid a wonderful compliment by someone telling me it was worse than [Led Zeppelin's unauthorized biography] "Hammer of the Gods."

Yeah, I would not have expected that.

That was why it was important for me to do the geek alerts and to balance out the playing with the working. We worked very, very hard.

We really rose from the ashes of Joy Division. It was, in many ways, like a Phoenix rising from the ashes. It was very difficult; it was hard work. It made you very vulnerable, because you didn’t know how you were going to be accepted with this new band, completely starting from scratch writing new material. It was a pretty harrowing time. I’m sure we could have all probably been diagnosed with PTSD.

Reading in the first part of "Substance," about New Order's first U.S. tour, you do really get the sense of how shell-shocked everyone was. It was people fumbling around in the dark trying to figure out “What are we going to do?”

Funnily enough, it was actually easy to make the decision to carry on, because we’d had what we say in England is a "sniff of the barmaid’s apron," where we knew where we wanted to go and where we wanted to be. It’s just that we didn’t want to ride on the coattails of Joy Division, which was a very, very strong decision and could have really backfired.

We were very lucky that the writing kernel of Joy Division survived into New Order and bloomed as prolifically as it did in Joy Division. We were still able to write great songs right from the word go. We still had a great team with a lot of belief in us. Our manager [Rob Gretton] was our biggest fan. We did have what you’d say is a solid backroom department. [Laughs] All we had to do was get on with it and write more songs.

That does help, to have the support system around you.

One of the great things about being in a group is also the worst thing about being in a group: You’re very mollycoddled, you’re encouraged to escape reality. We felt it was very important to throw ourselves into New Order in case we lost it. If somebody had come there and said, “Don’t worry, you don’t have to rush. You’re going to have a 41-year career,” you might have acted differently. But then you were scared it was going to disappear in a puff of smoke. It enabled us to escape grieving for Ian and Joy Division, really. We just sort of put it to one side.

And I have to say, amazingly, it worked. New Order became internationally successful. Joy Division never really made it internationally. It was a hell of a gamble.

You did a lot of research for "Substance," using other books about the band, and websites. What other kinds of things did you do to put the story together?

The actual book was 300,000 words and 1,200 pages, and the publisher insisted we cut it down to below 800. We actually lost a third of the book, which was heartbreaking. So it had a hell of a lot more detail, and a hell of a lot more stories and geek alerts in it. It was another book, basically. So we’ve got that held in reserve for whenever we can find a way to use it.

It’s like writing an LP: When you start with no songs, the LP seems unobtainable. It's like climbing Mount Everest and being right at the bottom. Then all of a sudden when you get to the top, you’ve sort of forgotten the pain that’s involved in getting there. The book took three years to write. I was under the impression that because my first book [2009's "The Haçienda: How Not to Run a Club"] took three years to write, and my second book ["Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division"] two years, I thought the third one would take a year. [Laughs] But as soon as you started delving into the details, there was just no chance of doing it.

The way that Bernard dispatched New Order in his book I thought was very unfortunate. I thought he did himself a great disservice with that, because I’m sure the fans would love to know what he thinks, what he thinks about as he writes, how he writes, his opinion of crafting a song. He didn't take the opportunity to do that. I'm the opposite, you see. I collect everything; he collected nothing. So I had a huge pile of crap, as my wife so fondly calls it, to delve into, and to look at from a business point of view and a band point of view. It was always me who was more involved in the business side of it, so I knew much more about it.

The saddest thing is I couldn’t ask any of the band. [Laughs] Because we’re at loggerheads, shall we say. So I had to do it without any of them. But it was nice to be able to sit down with people like our American manager [Tom Atencio] and [producer] Arthur Baker and Joe Shanahan, who runs [concert club] The Metro in Chicago — people like that — and see how they viewed New Order and what we achieved and what we did.

I did get an insight into New Order, funnily enough, doing the book. I have to say, when I started the book I was really, really upset and pissed off with New Order. So doing the book actually gave me a lot of solace, because you realized how big New Order were in the '80s. We started in May 1980 and finished in June 1990 with the England World Cup song ["World in Motion"]. And those 10 years were action-packed. I think half of the book is those first 10 years, then the second half of the book is the next 21, when we just kept splitting up all the time and getting back together again, and just swerve from one catastrophe to another.

But, yeah, it did make me feel quite fond to rekindle those old memories of how much you achieved in quite a short time – three or four years. It was amazing and, the cliché, I hate to say it, like a roller coaster ride. You got on in May 1980, and we didn’t think we were going to make the first corner. And then you went on this mad dash, ended up in America in 1988, ’89, playing to 25, 30 thousand people, six times more than we could play to in England.

Do you have any favorite authors or memoir writers who have inspired you as you’ve been writing these books?

I read musical memoirs; I suppose in that way I’m always hoping I can learn something — or maybe I can find a bit of sympathy in the pages, something sympathetic. [Laughs] Some of them are good; some of them are terrible. It’s usually the ones that you don’t expect that are nice. Gene Simmons’ autobiography, for instance, was a great rock autobiography. So was Rod Stewart’s ["Rod: The Autobiography"]. It was quite honest – very honest, actually, in the case of Gene Simmons — and very readable. And so you go through the whole gamut of how you want to be perceived with the book.

Lee Child is one of my favorite authors; I love the way he writes with Jack Reacher [series]. In England, there’s a guy called Ian Rankin, he’s one of my favorite authors. John Irving is my all-time favorite author. I’m delighted to be getting his new book ["Avenue of Mysteries"] for my birthday, so I’m looking forward to that.

It's a difficult thing, writing, and it’s a wonderful compliment when anybody says to you that they enjoyed the book. Especially when someone tells you they enjoyed all three. [Laughs] It does make me think for my fourth one, I have just got to get a bloody happy ending. I don’t know what it’ll be in, but it does have to be there. I couldn’t bear to do it without a happy ending.

It’s tough being an author, but I know that my mother would be delighted. She used to say to me, even when we were playing those 30,000-seat arenas and headlining Glastonbury, she always used to say to me, why couldn’t I get a proper job like my brother, who's a policeman. [Laughs] God bless her soul.

I suppose the problem with rock biographies is that, ultimately, all the stories are the same. You do have to work to make them interesting, shall we say, in some way or other. And our story has been independent as a group and changing the music world, not once but twice with Joy Division and New Order. And changing it culturally with [our label] Factory Records and the way we acted, the way you did your videos, the way you did your singles.

There’s a lot to be proud of, because you certainly weren’t making things easy for yourself. We were going out of our way, staying quite true to our punk ethics, and being difficult right from the word “go.” And it took a lot of time for people to adjust. The American record company in particular [found this out] when we signed to Quincy Jones’ label [Qwest]. Now, Quincy Jones was lovely; he was open to anything, and he was willing, if the music was good, to let you do more or less what you wanted. But Warner Bros., who were much more traditional, would fight all the way, tooth and nail. And our manager was struggling to keep our credibility and our credentials right through it. It did lead to some very interesting meetings, shall we say. [Laughs]

The book does chart the downfall, in my opinion, quite well, the way things changed and the way that we changed. And it has to be said that over the years, people do change. They have different ideals, different hopes, different aspirations, different ambitions. And that’s what happens in most groups: The very chemistry that makes them make great music is usually the exact same chemistry that makes them want to kill each other when they’ve been cooped up together for a few years.

There are so few bands these days that stay together for a lengthy duration of time. I mean, U2 have been together for like 40-ish years with the same lineup. You just don’t see that anymore.

The other thing with New Order was when they reformed without me — which was shocking, obviously, and especially with the way they handled the business affairs while they did it — you reacted very strongly against it. I think they thought I was going to disappear in a puff of smoke. To be excluded and to lose your group after 31 years, to lose your livelihood — it was a really, really shocking predicament to be in.

And I reacted against it, which has led to this huge legal battle now. Though now, five years on where I’ve been fighting, I start to think to myself. “Well, you know, I’ve done really well, actually.” The shock you had, again, was an overreaction. I’ve actually done really well touring, playing the music that I wrote and love, doing really well with it, having a great time because the angst is gone with the others. I don’t know whether the angst is still there among the others when they play. [But] I was thinking, “God, you know, I’m a different person now than when I started writing that book.” That was a weird revelation.

What other insights did you glean after you finished the book? What perspective did you gain on everything?

Changing the world is definitely a young man’s game, is what I would say. I think we had our shot — and we had a very, very good shot — but now it’s time for somebody else to do it. [Laughs] We’re very, in my opinion, even myself and New Order, we’re very ordinary now. And, really, the fans should be very happy, because they’ve got both. They’ve got me playing all the old stuff, and [New Order is out] playing a collection of greatest hits plus their new stuff. So if you’re a fan of New Order, you now get two bites of the cherry, if you like, as opposed to one.

The thing with the fans, which is the sad thing, is that they are divided because of what happened with our group. You get New Order fans that will come and see me and won't go and see the others because of what happened, and vice versa. And you get promoters who won’t put me on, and things like that. It’s quite weird. It’s like a divorce where everybody is put in an awful position where they have to choose which side they take. A lot of our friends have suffered from that, which is unfortunate I must say, [and are] still suffering from it now.

I was going to say, it’s a divorce that doesn’t end.

I hope it will come to an end soon. My friend said to me, "The only time it will work is when both of you are unhappy with the split." The thing is, at the moment, they’re very happy with the split, and I’m very unhappy, which is what gives it the angst. The battle must go on.

And that’s very sad. It’s such a sad statement that it only works when both people are unhappy.

Especially after 31 years. That group was my life for 31 years and then someone turned around and went, “You know, it’s not yours anymore. It’s gone now — forget it. Here’s 10 cents. Go on.” I defy anybody to go, “Oh, okay, mate, see ya. Enjoy yourselves.” Most people, 99.9 percent of the people, would go mental and go either running straight for their baseball bat or for their lawyer. You can’t really do that, can you, baseball bat politics anymore? [Laughs]

I guess both options would have their price in terms of expenses.

When someone said to me a long time ago, "Cocaine was God’s way of telling you you've got too much money," he got it wrong. Litigation is God’s way of telling you you've got too much money, without a shadow of a doubt.

Shares