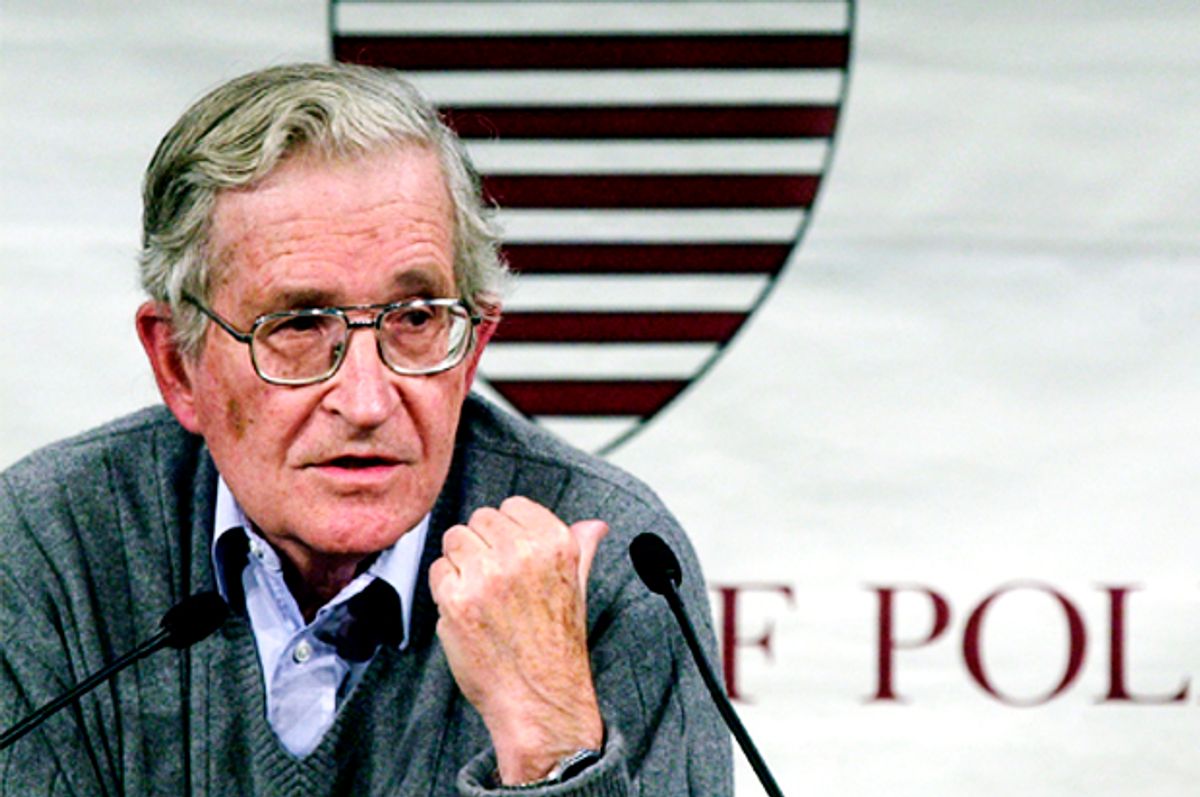

There are determining events, especially when we’re young and formulating our sense of the world: Times when we learn how to take ourselves, where to stand, how to move forward in a fresh way. For me, a key moment was stepping into the periodicals room of my college library in late February of 1967 -- I was a sophomore -- and reading an article in the New York Review of Books that caught my eye. It was “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” written by Noam Chomsky.

Nothing was quite the same for me after reading that piece, which I’ve reread periodically throughout my life, finding things to challenge me each time. I always finish the essay feeling reawakened, aware that I’ve not done enough to make the world a better place by using whatever gifts I may have. Chomsky spurs me to more intense reading and thinking, driving me into action, which might take the form of writing an op-ed piece, joining a march or protest, sending money to a special cause, or just committing myself to further study a political issue.

The main point of Chomsky’s essay is beautifully framed after a personal introduction in which he alludes to his early admiration for Dwight Macdonald, an influential writer and editor from the generation before him:

Intellectuals are in a position to expose the lies of governments, to analyze actions according to their causes and motives and often hidden intentions. In the Western world at least, they have the power that comes from political liberty, from access to information and freedom of expression. For a privileged minority, Western democracy provides the leisure, the facilities, and the training to seek the truth lying hidden behind the veil of distortion and misrepresentation, ideology, and class interest through which the events of current history are presented to us.

For those who think of Chomsky as tediously anti-American, I would note that here and countless times in the course of his voluminous writing he says that it is only within a relatively free society that intellectuals have the elbow room to work. In a kind of totalizing line shortly after the above quotation, he writes: “It is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies.”

This imposes a heavy burden on those of us who think of ourselves as “intellectuals,” a term rarely used now, as it sounds like something Lenin or Trotsky would have used and does, indeed, smack of self-satisfaction, even smugness; but (at least in my own head) it remains useful, embracing anyone who has access to good information, who can read this material critically, analyze data logically, and respond frankly in clear and persuasive language to what is discovered.

Chomsky’s essay appeared at the height of the Vietnam War, and was written mainly in response to that conflict, which ultimately left a poor and rural country in a state of complete disarray, with more than 2 million dead, millions more wounded, and the population’s basic infrastructure decimated. I recall flying over the northern parts of Vietnam some years after the war had ended, and seeing unimaginably vast stretches of denuded forest, the result of herbicidal dumps – 20 million tons of the stuff, including Agent Orange, which has had ongoing health consequences for the Vietnamese.

The complete picture of this devastation was unavailable to Chomsky, or anyone, at the time; but he saw clearly that the so-called experts who defended this ill-conceived and immoral war before congressional committees had evaded their responsibility to speak the truth.

In his usual systematic way, Chomsky seems to delight in citing any number of obsequious authorities, who repeatedly imply that the spread of American-style democracy abroad by force is justified, even if it means destroying this or that particular country in the effort to make them appreciate the benefits of our system. He quotes one expert from the Institute of Far Eastern Studies who tells Congress blithely that the North Vietnamese “would be perfectly happy to be bombed to be free.”

“In no small measure,” Chomsky writes in the penultimate paragraph of his essay, “it is attitudes like this that lie behind the butchery in Vietnam, and we had better face up to them with candor, or we will find our government leading us towards a ‘final solution’ in Vietnam, and in the many Vietnams that inevitably lie ahead.”

Chomsky, of course, was right to say this, anticipating American military interventions in such places as Lebanon (1982-1984), Grenada (1983), Libya (1986), Panama (1989), the Persian Gulf (1990-1991) and, most disastrously, Iraq (2003-2011), the folly of which led to the creation of ISIS and the catastrophe of Syria.

Needless to say, he has remained a striking commentator on these and countless other American interventions over the past half century, a writer with an astonishing command of modern history. For me, his writing has been consistently cogent, if marred by occasional exaggeration and an ironic tone (fueled by anger or frustration) that occasionally gets out of hand, making him an easy target for opponents who wish to dismiss him as a crackpot or somebody so blinded by anti-American sentiment that he can’t ever give the U.S. government a break.

I like “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” and other essays from this period by Chomsky, because one feels him discovering his voice and forging a method: that relentlessly logical drive, the use of memorable and shocking quotations by authorities, the effortless placing of the argument within historical boundaries and the furious moral edge, which -- even in this early essay -- sometimes tips over from irony into sarcasm (a swerve that will not serve him well in later years).

Here, however, even the sarcasm seems well-positioned. He begins one paragraph, for instance, by saying: “It is the responsibility of the intellectuals to insist upon the truth, it is also his duty to see events in their historical perspective.” He then refers to the 1938 Munich Agreement, wherein Britain and other European nations allowed the Nazis to annex the Sudetenland -- one of the great errors of appeasement in modern times. He goes on to quote Adlai Stevenson on this error, where the former presidential candidate notes how “expansive powers push at more and more doors” until they break open, one by one, and finally resistance becomes necessary, whereupon “major war breaks out.” Chomsky comments: “Of course, the aggressiveness of liberal imperialism is not that of Nazi Germany, though the distinction may seem rather academic to a Vietnamese peasant who is being gassed or incinerated.”

What he says about the gassed, incinerated victims of American military violence plucks our attention. It’s good polemical writing that forces us to confront the realities at hand.

What really got to me when I first read this essay was the astonishing idea that Americans didn’t always act out of purity of motives, wishing the best for everyone. That was what I had been taught by a generation of teachers who had served in World War II, but the Vietnam War forced many in my generation to begin the painful quest to understand American motives in a more complex way. Chomsky writes that it’s “an article of faith that American motives are pure and not subject to analysis.” He goes on to say with almost mock reticence: “We are hardly the first power in history to combine material interests, great technological capacity, and an utter disregard for the suffering and misery of the lower orders.”

The sardonic tone, as in “the lower orders,” disfigures the writing; but at the time this sentence hit me hard. I hadn’t thought about American imperialism until then, and I assumed that Americans worked with benign intent, using our spectacular might to further democratic ends. In fact, American power is utilized almost exclusively to protect American economic interests abroad and to parry blows that come when our behavior creates a huge kickback, as with radical Islamic terrorism.

One of the features of this early essay that will play out expansively in Chomsky’s voluminous later writing is the manner in which he sets up “experts,” quickly to deride them. Famously the Kennedy and Johnson administrations surrounded themselves with the “best and the brightest,” and this continued through the Nixon years, with Henry Kissinger, a Harvard professor, becoming secretary of state. Chomsky skewers a range of these technocrats in this essay, people who in theory are “intellectuals,” from Walter Robinson through Walt Rostow and Kissinger, among many others, each of whom accepts a “fundamental axiom,” which is that “the United States has the right to extend its power and control without limit, insofar as is feasible.” The “responsible” critics, he says, don’t challenge this assumption but suggest that Americans probably can’t “get away with it,” whatever “it” is, at this or that particular time or place.

Chomsky cites a recent article on Vietnam by Irving Kristol in Encounter (which was soon to be exposed as a recipient of CIA funding) where the “teach-in movement” is criticized: Professors and students would sit together and talk about the war outside of class times and classrooms. (I had myself attended several of these events, so I sat to attention while reading.) Kristol was an early neocon, a proponent of realpolitik who contrasted college professor-intellectuals against the war as “unreasonable, ideological types” motived by “simple, virtuous ‘anti-imperialism’” with sober experts like himself.

Chomsky dives in: “I am not interested here in whether Kristol’s characterization of protest and dissent is accurate, but rather in the assumptions that it expresses with respect to such questions as these: Is the purity of American motives a matter that is beyond discussion, or that is irrelevant to discussion? Should decisions be left to ‘experts’ with Washington contacts?” He questions the whole notion of “expertise” here, the assumption that these men (there were almost no women “experts” in the mid-’60s) possessed relevant information that was “not in the public domain,” and that they would make the “best” decisions on matters of policy.

Chomsky was, and remains, a lay analyst of foreign affairs, with no academic degrees in the field. He was not an “expert” on Southeast Asia at the time, just a highly informed and very smart person who could access the relevant data and make judgments. He would go on, over the next five decades, to apply his relentless form of criticism to a dizzying array of domestic and foreign policy issues -- at times making sweeping statements and severe judgments that would challenge and inspire many but also create a minor cottage industry devoted to debunking Chomsky.

This is not the place to defend Chomsky against his critics, as this ground has been endlessly rehashed. It’s enough to say that many intelligent critics over the years would find Chomsky self-righteous and splenetic, quick to accuse American power brokers of evil motives, too easy to grant a pass to mass murderers like Pol Pot or, during the period before the Gulf War, Saddam Hussein.

I take it for granted, as I suspect Chomsky does, that in foreign affairs there are so many moving parts that it’s difficult to pin blame anywhere. One may see George W. Bush, for instance, as the propelling force behind the catastrophe of the Iraq War, but surely even that blunder was a complex matter, with a mix of oil interests (represented by Dick Cheney) and perhaps naive political motives as well. One recalls “experts” like Paul Wolfowitz, who told a congressional committee on Feb. 27, 2003, that he was “reasonably certain” that the Iraqi people would “greet us as liberators.”

Fifty years after writing “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” Chomsky remains vigorous and shockingly productive, and -- in the dawning age of President Donald Trump — one can only hope he has a few more years left. In a recent interview, he said (with an intentional hyperbole that has always been a key weapon in his arsenal of rhetorical moves) that the election of Trump “placed total control of the government — executive, Congress, the Supreme Court — in the hands of the Republican Party, which has become the most dangerous organization in world history.”

Chomsky acknowledged that the “last phrase may seem outlandish, even outrageous,” but went on to explain that he believes that the denial of global warming means “racing as rapidly as possible to destruction of organized human life.” As he would, he laid out in some detail the threat of climate change, pointing to the tens of millions in Bangladesh who will soon have to flee from “low-lying plains … because of sea level rise and more severe weather, creating a migrant crisis that will make today’s pale in significance.”

I don’t know that, in fact, the Republican Party of today is really more dangerous than, say, the Nazi or Stalinist or Maoist dictatorships that left tens of millions dead. But, as ever, Chomsky makes his point memorably, and forces us to confront an uncomfortable situation.

As I reread Chomsky’s essay on the responsibility of intellectuals, it strikes me forcefully that not one of us who has been trained to think critically and to write lucidly has the option to remain silent now. Too much is at stake, including the survival of some form of American democracy and decency itself, if not an entire ecosystem. With a dangerously ill-informed bully in the White House, a man almost immune to facts and rational thought, we who have training in critical thought and exposition must tirelessly call a spade a spade, a demagogue a demagogue. And the lies that emanate from the Trump administration must be patiently, insistently and thoroughly deconstructed. This is the responsibility of the intellectual, now more than ever.

Shares