Sen. Mitch McConnell's ill-advised silencing of Sen. Elizabeth Warren during the debate over confirming Jeff Sessions to be attorney general read as a blatant act of sexism from a man who can't handle back talk from a woman. While that was no doubt an important element of it, it's also important to remember that Warren was trying to read a 1986 letter from Coretta Scott King, where she described Sessions' lengthy history of undermining the civil rights movement in Alabama.

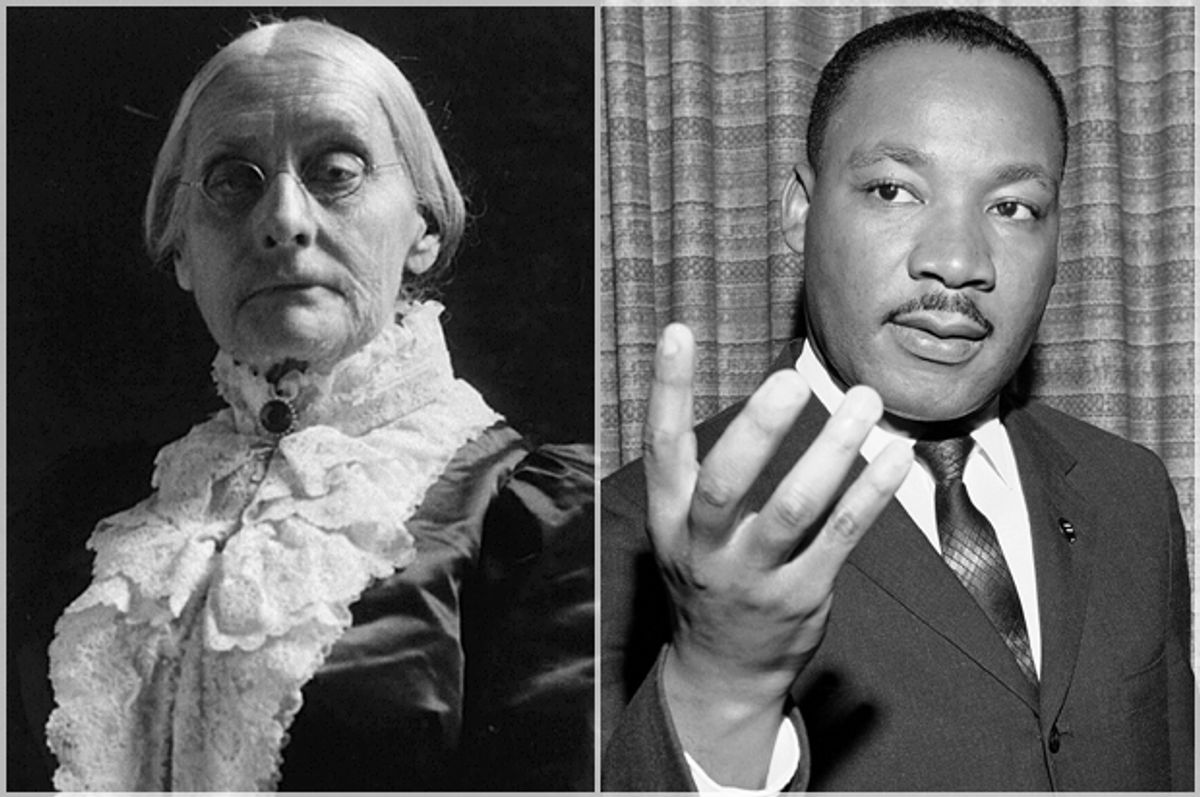

That letter angers Republicans because in the years since Martin Luther King Jr.'s 1968 assassination, conservatives have made an effort to remake King in their own image. Warren's attempt to read the letter by King's widow into the record served as an embarrassing reminder that King's politics had nothing in common with modern conservatism.

Call it the "dead progressive" problem. Conservatives love a dead progressive hero because they can claim that person as one of their own without having any bother that the person will fight back. In some cases, the right has tried to weaponize these dead progressives, claiming that they would simply be appalled at how far the still-breathing have supposedly gone off the rails and become too radical. Martin Luther King and his wife Coretta are just two prominent victims of this rhetorical gambit.

"Despite decades of its appropriation by liberals, [Martin Luther] King's message was fundamentally conservative," wrote Carolyn Garris of the Heritage Foundation a mere two weeks before Coretta Scott King's death in 2006.

"Had he lived, what would Martin Luther King would have thought of modern identity politics, of the world of 'microaggressions' and Black Lives Matter?" wrote David French last month in the National Review. He admitted that no one can say, but French strongly implied that King would have been appalled by modern progressivism.

After Warren delivered an embarrassing reminder that, no, the Kings were not actually in agreement with modern-day conservatives, White House press secretary Sean Spicer tried to do some clean-up duty.

"I can only hope if she was still with us today, that after getting to know [Sessions] and getting to see his commitment to voting and civil rights that she would" come to admire the nation's new attorney general, Spicer said on Wednesday, taking advantage of the fact that King cannot come back from the grave to dissuade him of that notion.

Historians I spoke with took a dim view of this conservative rewriting of Martin Luther King's legacy.

“One of the things King revealed that is unavoidable by looking at his work and his thoughts and his life is that the United States is, at its core, a racist country," said Robert Widell, an associate professor of history at the University of Rhode Island, over the phone.

“All that stuff has been stripped away from what people want to remember about King," he added. "It’s become part of this project of conservatives embracing and taking some of that rhetoric of the civil rights movement, twisting it around and making it seem that what they’re calling for in retrograde policies is actually consistent with what civil rights activists would have been calling for.”

Stanford University historian Clayborne Carson explained by telephone, “King, when he was assassinated, was probably at the lowest point in his popularity."

The effort to reinterpret or appropriate King's legacy began immediately, said Carson, who was handpicked by Coretta Scott King to handle her husband's papers. "After his death, national leaders were trying to get into the funeral, pushing aside people who had worked beside King, to get into Ebenezer Church — people a month earlier who would not have wanted to be on the stage with him.”

This conservative habit of cherry-picking quotes from progressive heroes in an effort to claim them for the conservative cause isn't just aggravating for historians. In some cases, it can become personal.

Ann Gordon of Rutgers University runs the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers Project and for years she has seen anti-choice activists distort her research in order to argue falsely that 19th-century suffragists were ideologically opposed to legal abortion — and to imply that modern feminism has therefore lost its way. Anthony, in particular, has been elevated by anti-choicers as some kind of foremother and is often portrayed as vocally anti-abortion. One major anti-choice group, the Susan B. Anthony List even takes its name from the famous suffragist.

In a phone call, Gordon emphasized to me that there is absolutely no evidence that Anthony was against abortion. Yet it wouldn't be fair to call her pro-choice either, Gordon explained. Instead, Anthony largely ignored the issue, as it wasn't really at the forefront of feminist discourse at the time.

Anti-choicers cobble together a fake history of Anthony's opposition to abortion with a few cherry-picked quotes, most of which come from an article that Anthony didn't even write but simply published in a newsletter that was focused on lively debate. But they have also fished into one of Gordon's books, "The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: National Protection for National Citizens, 1873 to 1880," for a couple of diary entries where Anthony mentions, in passing, that her sister-in-law has taken ill from an abortion.

"Sister Annie is in bed — been sick for a month — tampering with herself," Anthony wrote on March 4, 1876. ("Tampering with herself" would have been understood as a euphemism for abortion in the 19th century.)

"Sister Annie better — but looks very slim — she will rue the day she forces nature," Anthony wrote on March 7, 1876.

From those diary entries, anti-abortion activists have built an entire fantasy that Anthony was some kind of rigid anti-choice ideologue who would shame contemporary feminists for their pro-choice politics.

“I’ve argued there’s no way in the world to convert this into a call to have a movement against abortion or a call to criminalize abortion or anything of the above," Gordon said. "You could read it as evidence of how common abortion was, if Susan B. Anthony’s own sister-in-law aborted at least once.”

It's true that one can detect a note of judgment in Anthony's tone in the diary, but that is likely due more to her squeamishness about sex than an ideological statement about abortion. After all, Anthony chastised Stanton for having children, writing after hearing of her friend's seventh pregnancy, "I only scold now that for a moment’s pleasure to herself or her husband, she should thus increase the load of cares under which she already groans."

Gordon added, “It’s pretty bizarre to take a 19th-century virgin as your model on sexual questions."

Stanton, who, if we take Anthony's word for it, was a big fan of sex, had sharper words on the matter. Gordon referred me to an 1855 speech in which Stanton said, “Did it ever enter into the mind of man that woman, too, had an inalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness? Did he ever take in the idea that to the mother of the race, and to her alone, belongs the right to say when a new being should be brought into the world?”

In the 2006 Dixie Chicks song "Lubbock or Leave It" Natalie Maines sings about the statue of Buddy Holly in Lubbock, Texas: "I hear they hate me now/ Just like they hated you/ Maybe when I'm dead and gone/ I'm gonna get a statue too."

For historians who study progressive figures, the sentiment is a familiar one.

“It’s always better to have prophets in retrospect, in the rearview mirror," Carson said. "While they’re around, they’re bothersome people." He added, "There’s always that thing where when they’re no longer around, they’re no longer a threat."

Shares