Roy Wood Jr.’s head kept banging against a dangling light fixture. He was sitting at the front of the Olive Tree Café, with his back to MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village, getting ready for what would be a six-set night. “I try to block out one or two weekends a month in the city to do stand-up, because what's the point of living here as a comic if you’re not on stage,” Wood said, the conical stained-glass light hovering over his broad forehead like a hippie dunce cap.

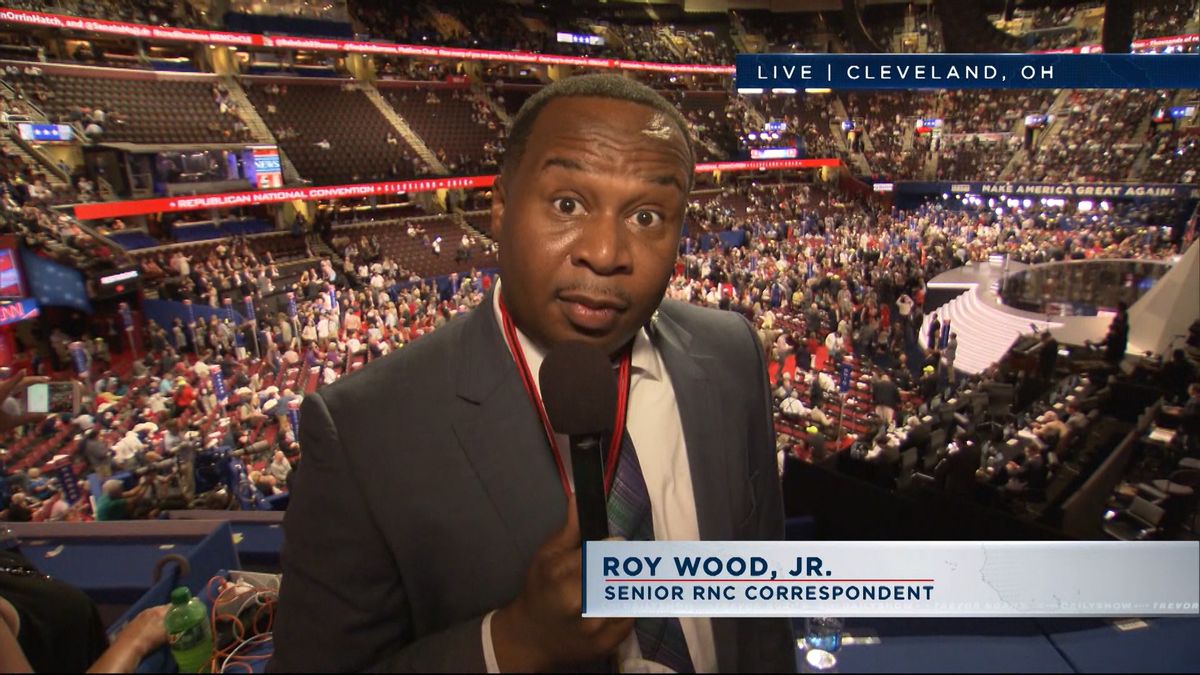

It was a warm Thursday for early February, a fine night for hopping from club to club. Though such evenings are ritualistic for Wood, on this night his performing was dictated by a purpose. Wood, who has become best known through his role as a “Daily Show” correspondent, was honing a five-minute set that he would perform on “The Tonight Show” in four days — a set intended to promote his special, “Father Figure,” which will be released Sunday, Feb. 19, on Comedy Central.

The special is Wood’s first in his 19-year career. He began performing stand-up when he was a junior at Florida A&M, studying broadcast journalism. A friend of his was dating a girl at nearby Florida State and would sometimes bring Wood along as a wing-man. During one trip, Wood entered a student talent night and told jokes. He may have been searching for lust at Florida State, but he found a lasting love. He rearranged his course schedule so that he could spend weekends taking Greyhound busses around the south, performing five- to ten-minute sets at clubs from Tallahassee to Atlanta, or his hometown of Birmingham.

The broad demographic of the club patrons taught Wood to craft jokes that would appeal to any audience. “If you're telling jokes to four different demos in one week, you're better served creatively if you have one joke that all four of them can laugh at,” he said.

The types of jokes Wood wanted to tell were ones that could deconstruct societal norms. “Growing up I watched a lot of Chris Rock, Martin Lawrence and George Carlin,” he said. “My first year of comedy was a bad Martin Lawrence impersonation. I watched so much Martin Lawrence, I was Martin Lawrence. And it didn’t work for me.”

After graduating, Wood returned to Birmingham to work as an urban morning show host. He spent 11 years on the radio, earning notoriety for his riotous prank phone calls, and eventually getting his own eponymous show for which he would win several awards. But during that time, he continued to hustle the South’s barren comedy scene.

By the time he was in his late 20s, Wood found his voice and stage persona — fast-talking, distinctly Southern, someone who would back up bold statements with thoughtful takes (e.g., the first line in his special questions getting rid of the Confederate flag). That perspective was distinct from the style of comedians who had developed in the comedy hubs of New York, Los Angeles and Boston, and “The Daily Show” took notice.

“Being a black, Southern-born road comic who has traveled to every corner of the U.S. means that Roy brings to the show a point of view shaped not by a bubble but rather every real edge of this world,” said Trevor Noah . “He's also devastatingly funny.”

On “The Daily Show,” Wood often plays the role of the incredulous or wronged black man — such as in a bit about whether all police are racist. But many of his best segments have been unrelated to race. In a bit at Super Bowl media day, he tried to interview players without bringing up Donald Trump — “alternative stats” and proper vetting undid his plan. And a story about the Army Corps of Engineers’ wasteful spending shone a light on the problematic New Madrid Floodway, a project for which President Obama cut funding just before leaving office.

“The thing that ‘The Daily Show’ has given me that I feel like my stand-up didn't have before is the compulsion to dig deeper on issues,” Wood said. And yet, working there has not satiated his voice. “There's a lot of stuff that's in my system that I can't get out on ‘The Daily Show,’” he said.

One of those things is the minutiae of everyday life — the irritations at the supermarket checkout line, the anticlimactic job of a co-pilot, and arguments with his girlfriend over, say, dangling light fixtures. These were the topics Wood would talk about on “The Tonight Show.” As he moved from club to club, he calibrated and tuned, focusing the first few sets on his material and the last few on his delivery.

After performing at the Cellar, he realized the first line — “I lost an argument at Ikea. My girl, we got into it over lamps” — wasn’t quite right. “I'm okay with how the joke opens about losing an argument at an Ikea,” he explained, as he walked around the corner to the Cellar’s sister club, the Village Underground. “But I feel like there's a funnier way to establish that. Only one of two things is funny. Either the location of the argument or what we were arguing about. Originally, the joke was set up so we were talking about lamps. But the word 'lamps,' the vernacular of it doesn't — I just feel like 'lightbulbs' connects better.”

When we got to the Underground, the night’s host, Ray Ellin, was finishing his introductory set. As Wood waited in the back of the club and thought about a new opening, his thoughts were interrupted by a whoosh and roar. A woman’s hair fell into a candle and caught on fire. “You alright?” Ellin said. “Now, I did say that this was not a safe space; however, I didn’t mean to light your head on fire. The aroma reminds me of summer camp. It really smells like you’re cooking hotdogs and marshmallows over here.”

“Oh, you can smell it, bro,” Wood said, crinkling his nose. When he went on, he neglected to change the first line.

An hour later, he was in Brooklyn, at a bar that embraced all of Brooklyn’s stereotypes — minimal vintage furniture; a majority of patrons wearing beanies; a carnival’s worth of activities, including bowling, pool, televised sports, and comedy.

Wood tinkered. “I lost an argument at Ikea in the lamp department.” Still not right. But this go-round Wood successfully adjusted his cadence. “On late night, you're performing for a lot of people in Middle America,” he said. “A lot of people who don't necessarily keep up with black vernacular. I always talk too fast and jokes get lost. So I have to physically remember to slow down.”

In his special, Wood was able to slow down to great effect. “Father Figure” was filmed in Atlanta, in front of a mostly black audience. Throughout, he moves and speaks deliberately, clearly comfortable. “Because there’s a lot of race in my show, I wanted to be in the black people capital of America,” he said. “I wanted to be in the South, I wanted to be somewhere where I felt at home, amongst family for lack of a better phrase.”

Wood was quite literally in front of family. The special opens with him addressing his 9-month-old son backstage, coaching him on how to be black in America. The special is a time capsule of his life and the world at this moment, which he thinks his son might watch in the year 2029, through his “YouTube glasses.” In it, Wood confronts the universal tendency to think that you’re right and the other side is stupid. “We may not agree on the problem. We may not agree on the solution. But as long as we can agree that something's wrong, that's a starting place,” he says.

When asked about that line, Wood explained how well-intentioned people can reduce others’ experiences. “Like there's so many people who think the black experience is A, when it's actually A, B, C and D,” he said. “And I hope that whatever blackness my son identifies with when he's older, he can recognize that there's nothing wrong with being who he is and feeling the way he feels. Because there's something wrong, yeah there's something wrong in the world. But it's like, if I can figure out a way for my son to have opinions and think about other people then I've done something, man.”

While looking at the world in a deeper and more critical way means having greater empathy, for Wood, sometimes it can also mean thinking hard about an argument over lightbulbs.

“I lost an argument with my girl over lightbulbs.” Yes.

Shares