Only Donald Trump can save “La La Land.” Tonight, Damien Chazelle’s innocuous but polarizing Los Angeles musical will win the Academy Award for Best Picture — in addition to many other things, probably — and, barring some outburst or significant action from the president, the film will bear the full fury of Internet-based media. Be prepared to read many tweets joking that “Moonlight won the popular vote.”

Like the Super Bowl and the Grammys, the Oscars have been made to be about subtext rather than text. The Best Picture race is black vs. white, progressive vs. conservative, good vs. bad.

On the one hand, this all makes sense. Awards shows are rituals, and rituals serve to determine who is an insider and who is an outsider; the anthropologist Clifford Geertz theorized that they “encapsulate a worldview that serves as both a ‘model for’ and a ‘model of’ reality.”

Diversity and progressiveness remain on the periphery when a team led by a (white) golden boy and a (white) dark Sith Lord beats a team of underdogs led by dynamic (black) skill players or when a traditional album of soul ballads made by a white woman beats a tour de force R&B album made by a black woman. Both literally and symbolically, conservative forces have been more successful at modeling reality since November.

Still, the whole thing feels reductive and a little bit arbitrary. Why is Best Picture the only award that matters? And why is Best Picture a two-movie race, between “La La Land” and “Moonlight”?

What would be the reaction if “Hidden Figures,” a biopic in the mold of traditional Oscar bait but for the fact that it features a cast of black women, won Best Picture? What about if “Arrival,” a gorgeous, mind-bending film with a progressive message but a predominantly white cast, wins?

The Oscars are a historical record, and the significance of the Best Picture award is inherent in its title; it is the night’s most comprehensive award. But why is there not more uproar among those who want to maintain an accurate record of what is “best” that two of the year’s most ambitious and well-executed films, “OJ: Made in America” and “Toni Erdmann,” were not considered in the Best Picture race because they are not American feature films?

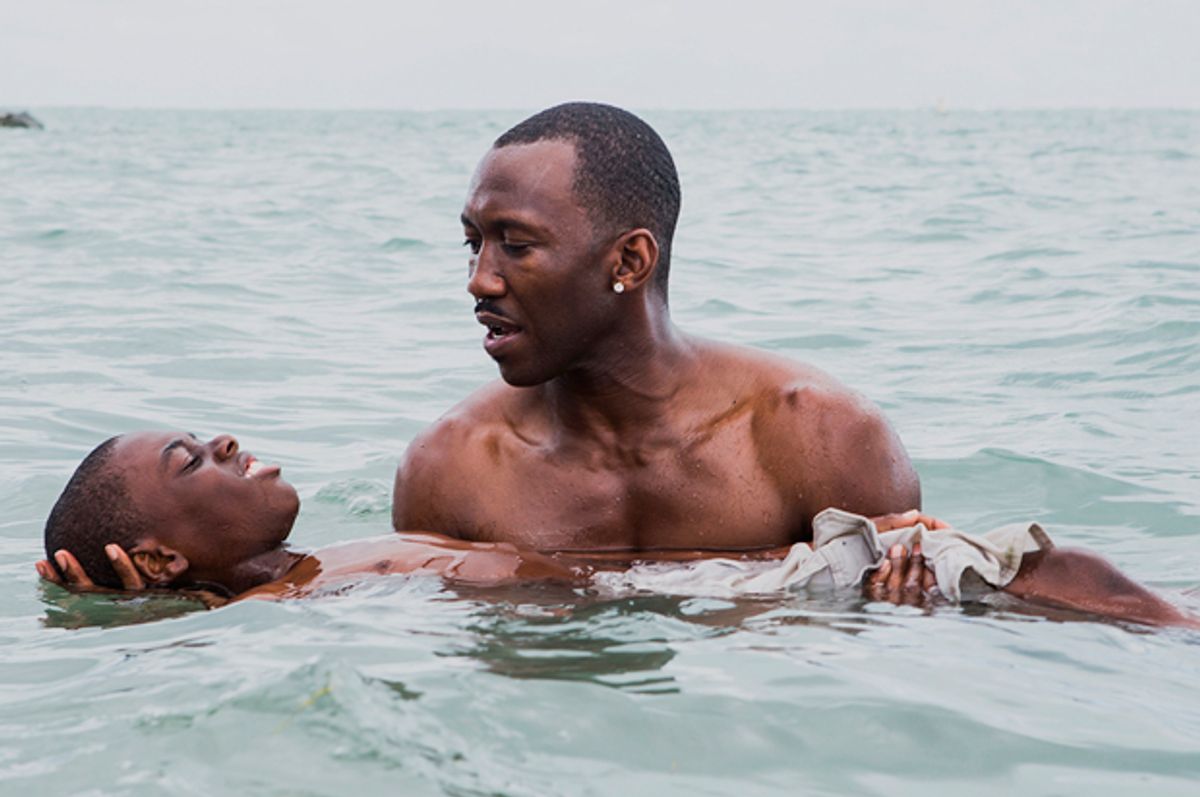

Of course, there are practical reasons why the Oscars matter, and why movie fans should want more progressive, diverse, and ambitious films to win Oscars. The majority of Americans can’t name a single Best Picture nominee, according to a recent Hollywood Reporter poll. So winning Best Picture can introduce a film to audiences that might not otherwise discover the film — in the case of “Moonlight,” an intimate portrait of a gay black man’s coming of age, that would be significant.

Winning awards also gives filmmakers clout and leverage. “There's instant prestige, so you suddenly become more attractive to studios and producers,” said Rocco Caruso, a producer who has worked with the Oscar-winning director Jonathan Demme for the past six years. “If you win for director, you suddenly are in a different category. So you're given projects you wouldn't have been offered before. People think of you in a different way. You're now prestige, so when [studios] have a prestige project, winners are instantly at the top of the list. And the minute you win, your rate goes up; if you're a director making $200,000 and you win an Academy Award, now you're in the million-dollar category.” In this way, the Best Director race is more important than the Best Picture race for the creative futures of the two Best Picture frontrunners’ directors.

The Academy Award for Best Picture might not even have much of an impact on the director of whichever film wins. When “Driving Miss Daisy” won Best Picture in 1989, its being awarded was widely maligned. In a phone interview, the film’s director Bruce Beresford said, “I'm very doubtful that the award had any impact on [what types of movies I was able to make afterwards]. Because at the time of the awards, my name was never mentioned. I didn't get nominated. It was almost like it directed itself. It didn't really work out that well for me. I was very glad that the film won, of course. But it didn't personally make any difference at all to me.”

Beresford speculated that had he won Best Director, things would have been different. “That would've put my price up to no end. Because you'd get a certain amount of publicity out of that. There would be interviews and articles and all that kind of thing. Your name in front of all the producers. That would make a difference.”

Best Picture is the award that will receive the most attention on Sunday. But ultimately, fans invested in a better cinematic future would do well to listen to Jenkins, who said in a recent interview, “[T]here's no reason that any of us should clean up. I think the best version is all of us sharing all these many things.” The more quality films that are recognized on Sunday, the more films that casual movie fans might discover. And the more quality films that casual fans discover, the more projects there will be, period.

Shares