Some politicians have never made a secret of their desire to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as its companion agency the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). ![]()

Each of these agencies have traditionally been regarded as bastions of “liberalism,” making them prime targets for conservatives in the culture wars.

While I would dispute that characterization, opponents’ ostensible reason for killing off the NEA in particular is equally flimsy: cost savings. Costing taxpayers $148 million in fiscal year 2016, the NEA made up a minuscule fraction of the $3.9 trillion the U.S. government spent. (If you add in the other two agencies on the chopping block, the total was still just $741 million.)

At the same time, NEA opponents tell those who worry their local communities will see arts funding dry up, don’t worry, private sources will emerge to make up for the difference. Sadly, nothing could be further from the truth.

That’s because it’s the government funding itself that often drives the donations in the first place by energizing private philanthropy. And since privatization of arts funding is one of the supposed reasons for killing off the NEA, the argument begins to fall apart.

If we focus on the allocations to museums in particular, my particular focus, the proposed cuts could lead to a reduced financial health of all museums, especially smaller museums in the middle of the country.

Where the money goes

The NEA’s budget of $148 million is divided up among 19 different categories, including arts education, dance, music and opera. (The NEH gets a similar allocation of $148 million, while the CPB — which funds National Public Radio and PBS — gets $445 million.)

The loss of funds to each arts category would be unfortunate, but I would argue the museum funding cuts would be especially damaging. A closer look at the impact on museums is also illustrative of the deleterious effect of eliminating the NEA for American arts more generally, which generated $704 billion in economic activity in 2013. Another study showed that each dollar of investment in nonprofit cultural institutions creates $1.20 to $1.90 in per capita income.

The NEA allocated $4.25 million in 2016 for 129 grants, most in the range of $15,000 to $25,000, which went to museums around the country. Almost all of the grants had the purpose of facilitating the exhibition of and access to American art, especially to low-income individuals, the handicapped and to children.

The NEA’s $15,000 grant to the Cleveland Museum of Art is emblematic of where the money goes:

“To support the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Centennial celebration festival. The summer weekend festivities will activate the entire campus of the museum and will include music, visual and performing arts, family programming, and a concert by the renowned Cleveland Orchestra . . . Collaborations with community organizations including the Orchestra, Zygote Press [exhibition venue], the Cleveland Public Library and the Boys and Girls Club will help the museum reach new audiences.”

Two aspects of this and almost all the other small grants are that children are central beneficiaries and that the intent is to bring American achievements to light. In other words, they aren’t elitist in any sense of the word, nor particularly “liberal” in terms of politics.

As the arts advocacy group Theatre Communications Group put in 2013 testimony before Congress:

“The arts infrastructure of the United States is critical to the nation’s well-being and its economic vitality. It is supported by a remarkable combination of government, business, foundation and individual donors. It is a striking example of federal/state/private partnership. Federal support for the arts provides a measure of stability for arts programs nationwide and is critical at a time when other sources of funding are diminished.”

NEA seal of approval

And while these grants most often cover only a fraction of the total cost of the project or program in question, their real power is as a “seal of approval,” essentially assuring private donors (individuals or companies) of a project’s quality.

The NEA grants typically are met with matching donations that multiply what the endowment chipped in, according to the NEA’s recent reports. On average, each grant is matched by $9 from state, local and private sources, generating more than $600 million in extra funding in 2015.

This “imprimatur” has, since today’s NEA was created in 1965, become a hallmark for attracting private funds and widespread art education for Americans. One function of NEA subsidies as revealed in the details of specific grants for 2016 is to facilitate exhibitions, both from permanent collections and for borrowed exhibitions.

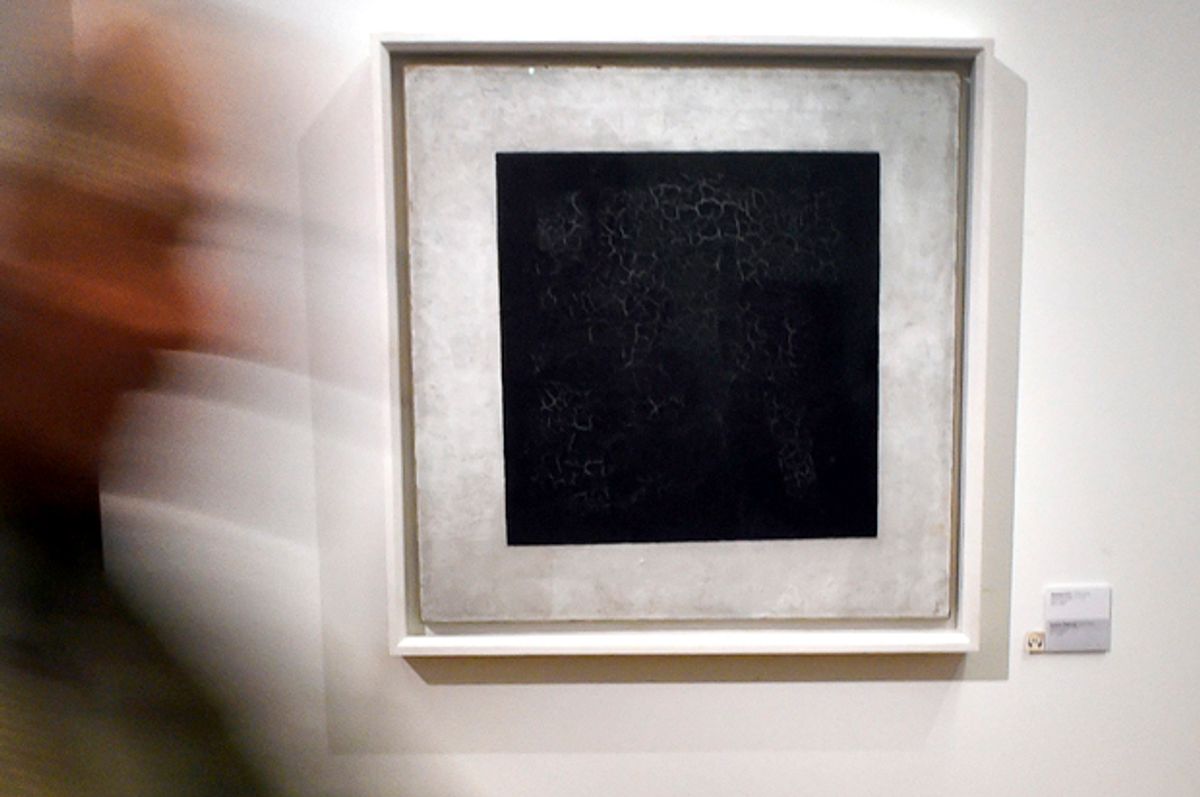

The exhibitions have become more important in view of the exponential prices of both historical and contemporary art. The entire budget of the NEA, for example, would not purchase a single first-rate Picasso. “Women of Algiers (Version ‘O’)” fetched $179 million when Christie’s auctioned it off in May 2015. NEA grants help attract private financing that allows museums to create exhibitions of high quality.

Naturally, the “private money attraction” feature of the NEA applies to all categories of its recipients, but I believe that it has special relevance for all museums in the heady auction prices for art.

Costs and benefits

When the benefits of the NEA are assessed and weighed against other government expenditures, the relative costs and benefits to society are apparent.

As Winston Churchill purportedly opined when it was suggested that the arts be cut from government funds to help the war effort during World War II, “Then what we are fighting for?”

The links between museum prosperity and American culture are also worth that effort.

![]()

Robert Ekelund is an eminent scholar and professor of economics emeritus at Auburn University.

Shares