When Republican Representative Jason Chaffetz took to the airwaves Tuesday to defend his party’s flailing Affordable Care Act replacement plan, he told CNN, “Americans have choices … so, maybe, rather than getting that new iPhone that they just love, and they want to go spend hundreds of dollars on that, maybe they should invest in their own healthcare.” Pushback was swift as many were quick to point out the Congressman was equating a $700 phone to healthcare costs that can often spiral into six figures, but some were equally shocked by the callousness of his remarks.

Was Chaffetz insinuating that the poor would rather spend money on frivolous things than their own self-care?

To people like myself, who grew up poor, this criticism is certainly nothing new. In conversations with Republicans about the challenges facing my working-class family, I’ve gotten used to being asked how many TVs my parents own, or what kind of cars they drive. At the heart of those questions is a lurking assumption that Chaffetz brought into the light: Maybe the poor deserve their lot in life.

This philosophy, while absurd on its face, effectively cripples any momentum toward helping suffering populations and is an old favorite of the Republican Party. It’s the same reasoning that led Ronald Reagan to decry “welfare queens” and Fox News to continually criticize people on assistance for buying shrimp, soft drinks, “junk food,” and crab legs. It gives those disinclined to part with their own money an excuse not to feel guilty about their own greed.

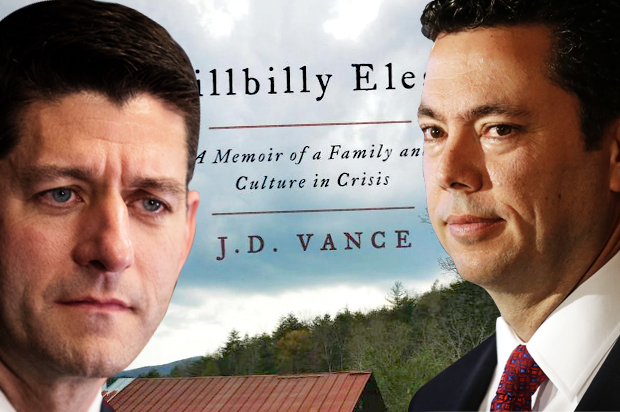

To further quell their culpability and show that the American Dream still functions as advertised, conservatives are fond of trotting out success stories — people who prove that pulling one’s self up by one's bootstraps is still a possibility and, by extension, that those who don’t succeed must own their shortcomings. Lately, the right has found nobody more useful, both during the presidential election and after, than their modern-day Horatio Alger spokesperson, J. D. Vance, whose bestselling book “Hillbilly Elegy” chronicled his journey from Appalachia to the hallowed halls of the Ivy League, while championing the hard work necessary to overcome the pitfalls of poverty.

Traditionally this would’ve been a Fox News kind of book — the network featured an excerpt on their site that focused on Vance’s introduction to “elite culture” during his time at Yale — but Vance’s glorified self-help tome was also forwarded by networks and pundits desperate to understand the Donald Trump phenomenon, and the author was essentially transformed into Privileged America’s Sherpa into the ravages of Post-Recession U.S.A.

Trumpeted as a glimpse into an America elites have neglected for years, I first read “Hillbilly Elegy” with hope. I’d been told this might be the book that finally shed light on problems that’d been killing my family for generations. I’d watched my grandparents and parents, all of them factory workers, suffer backbreaking labor and then be virtually forgotten by the political establishment until the GOP needed their vote and stoked their social and racial anxieties to turn them into political pawns.

In the beginning, I felt a kinship to Vance. His dysfunctional childhood looked a lot like my own. There was substance abuse. Knockdown, drag-out fights. A feeling that people just couldn’t get ahead no matter what they did.

And then the narrative took a turn.

Due to references he downplays, not to mention his middle-class grandmother’s shielding and encouragement, Vance was able to lift himself out of the despair of impoverishment and escaped to Yale and eventually Silicon Valley, where he was able to look back on his upbringing with a new perspective.

“Whenever people ask me what I’d most like to change about the white working class,” he writes, “I say, ‘the feeling that our choices don’t matter.’”

The thesis at the heart of “Hillbilly Elegy” is that anybody who isn’t able to escape the working class is essentially at fault. Sure, there’s a culture of fatalism and “learned helplessness,” but the onus falls on the individual.

As Vance writes: “I’ve seen far too many people awash in genuine desire to change only to lose their mettle when they realized just how difficult change actually is.”

Oh, the working class and their aversion to difficulty.

If only they, like Vance, could take the challenge head on and rise above their circumstances. If only they, like Vance, weren’t so worried about material things like iPhones or the “giant TVs and iPads” the author says his people buy for themselves instead of saving for the future.

This generalization is not the only problematic oversimplification in Vance’s book — he totally discounts the role racism played in the white working class’s opposition to President Obama and says, instead, it was because Obama dressed well, was a good father, and because Michelle Obama advocated eating healthy food — but it would be hard to understate what role Vance has played in reinvigorating the conservative bootstraps narrative for a new generation and, thus, emboldening Republican ideology.

To Vance’s credit, he has been critical of Donald Trump, calling the working class’s support of the billionaire a result of a “false sense of purpose,” but Vance’s portrait of poor Americans is alarmingly in lockstep with the philosophy of Republicans who are shamefully using Trump’s presidency to forward their own agenda of economic warfare. Certainly Jason Chaffetz’s comments are fueled by the same low opinion of the poor as Vance’s, as is Speaker of the House Paul Ryan’s legislative agenda, which is focused on disabling the social safety net.

Though Vance’s name doesn’t appear in the Republican ACA replacement bill, the philosophy at the heart of it is certainly in tune. While the proposed bill would cost millions of Americans their access to care — Vance himself tweeted a link Tuesday to a Forbes article that stated as much while lauding the legislation — it makes sure to benefit the wealthy, gives a tax break to insurance CEOs and moves the focus of health care in America to an age-based model instead of income.

The message is loud and clear: Help is on the way, but only to those who “deserve” it.

And how does one deserve it?

By working hard. And the only metric to show that one has worked sufficiently hard enough is to look at their income, at how successful they are, because, in Vance’s and the Republican’s America, the only one to blame if you’re not wealthy is yourself. Never mind how legislation like this healthcare bill, cuts in education funding, continued decreases in after-school and school lunch programs, not to mention a lack of access to mental health care or career counseling, disadvantages the poor.

Of the problems facing working-class America, Vance writes in “Hillbilly Elegy,” “There is no government that can fix these problems for us.”

And, at least partially, one has to agree.

There is no government that can fix these problems, or at least, no government we have now.