In 1971 a 19-year-old man named William Powell, inspired by the anti-Vietnam War counterculture boom, wrote a book that would connect the Columbine massacre in 1999; the 2013 shooting at Arapahoe High School, in Colorado; a robbery by the Black Liberation Army; and a 2011 Tucson, Arizona, shooting. That book is called “The Anarchist Cookbook,” and it is a manual of sorts: With a radical libertarian’s convictions, Powell provided instructions for making DIY explosives, phreaking devices, and drugs, such as LSD.

“If I could come out in this book and advocate complete revolution and the violent overthrow of the United States of America, without being thrown in jail, I would not have written ‘The Anarchist Cookbook,’ and there would be no need for it,” he wrote in the book’s introduction.

“The Anarchist Cookbook” was controversial from the time of its publishing. The FBI deemed it “one of the crudest, low-brow, paranoiac writing efforts ever attempted.” And Sen. Diane Feinstein has said the book is not protected by the First Amendment and its contents should be banned from the internet.

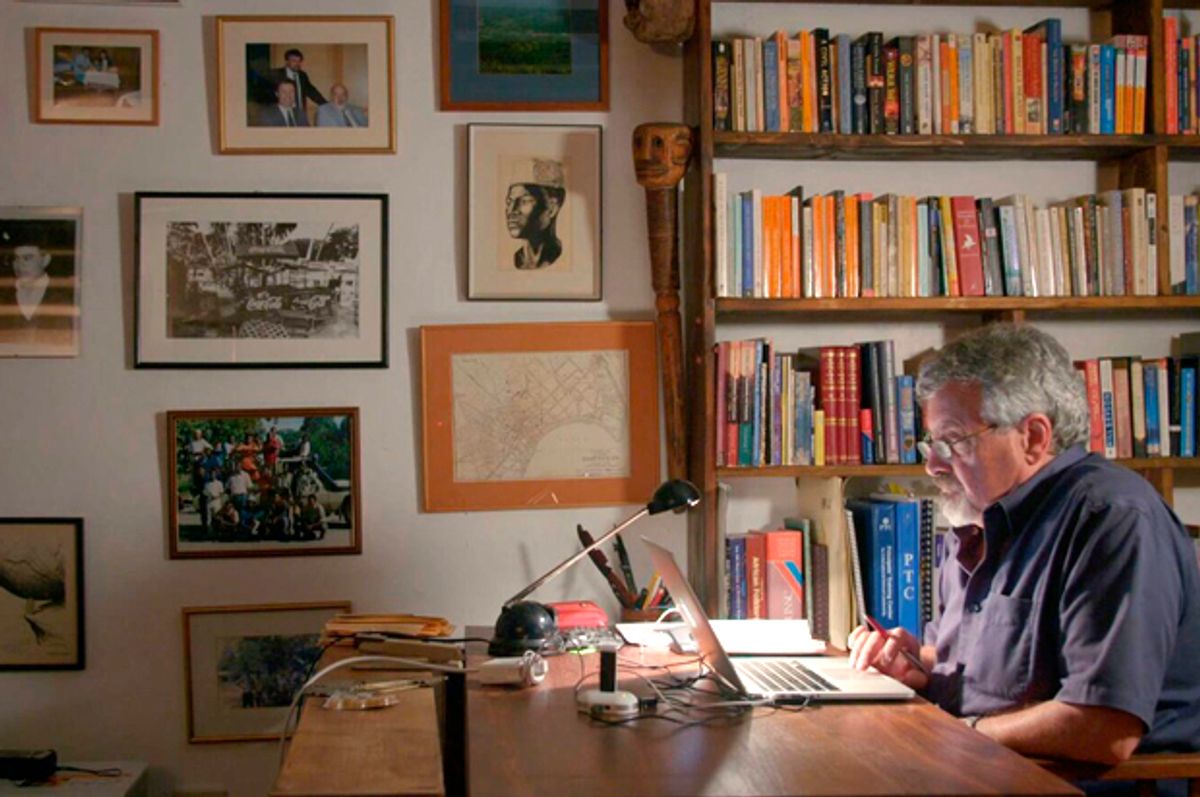

Today at age 65, Powell does not project the image of an anarchist. He is married and works as a teacher of children with learning disabilities. He wears sweater vests and spectacles and, with his goatee and wide build, could pass as the brother of Salman Rushdie. He has publicly denounced the book’s message and argued for it to be taken out of print. “Over the years, I have come to understand that the basic premise behind the Cookbook is profoundly flawed,” he wrote in a 2013 Guardian op-ed. “The anger that motivated the writing of the Cookbook blinded me to the illogical notion that violence can be used to prevent violence.”

So how does Powell reckon with the damage wrought by his writing?

That's the question that undergirds Charlie Siskel’s new documentary, “American Anarchist.” Siskel is best known for producing the documentaries “Bowling for Columbine” and “Finding Vivian Maier” (which he also directed) — and for being film critic Gene Siskel’s nephew. Charlie Siskel figures prominently in his newest picture. Though we never see Siskel on screen, we hear his voice throughout the film. He is a tenacious — bordering on pugnacious — interviewer, determined to ask Powell the aforementioned question from every possible angle.

Powell’s answers are complicated. In the new film he says the first time he found out that the book was connected to an act of violence was when a friend who had seen Siskel’s “Bowling for Columbine” — which draws the connection — emailed Powell, telling him that the shooters had had copies of his book. Powell says that knowledge of the violence has filled him with remorse, but he distinguishes remorse from regret. When Siskel asks if his instinct was to try and learn more, Powell says, “There was part of me that didn’t want to know anything about it. And there was part of me that was torn up about it that did want to learn more.”

For the most part, Powell has chosen to do the former. Aside from doing a few brief Google searches on the book, he did not set out to learn all the ways it was connected to violence. According to Powell, Siskel’s visit marks the first time he has heard about most of the book’s links to violence. That’s partially because Powell isn’t a masochist. But more so, he says, it’s because much of his career has been spent teaching and living abroad, largely disconnected from American news and the internet.

That Powell knows so little of the book’s aftermath and that he has tried to put the book behind him is shocking to Siskel. From the view of an outsider, “The Anarchist Cookbook” is the defining act of Powell’s life. Much of the film is spent on trying to comprehend how and why Powell did not do more, in Siskel’s framing, “to deal with and confront the book.”

Many of Siskel’s questions are leading and repetitive and Powell understandably grows perturbed. (The viewer does, too.) Though Siskel’s interrogating can be poor viewing, there’s a point to it. Powell argues that he’s ultimately not the one who pulled the trigger in any of these cases; he analogizes his role to that of a gun manufacturer. The film is about the cognitive disconnect and justification throughout the line of massacre production.

Of course, the film is also about how actions accomplished when we’re young have consequences; the permanence of published words; the consequences of free speech; Americans’ sense of belonging; and what a life is defined by. That is where Siskel’s film excels: By choosing a supremely complicated subject, the film tells several stories — all more interesting than the book that inspired it all.

Shares