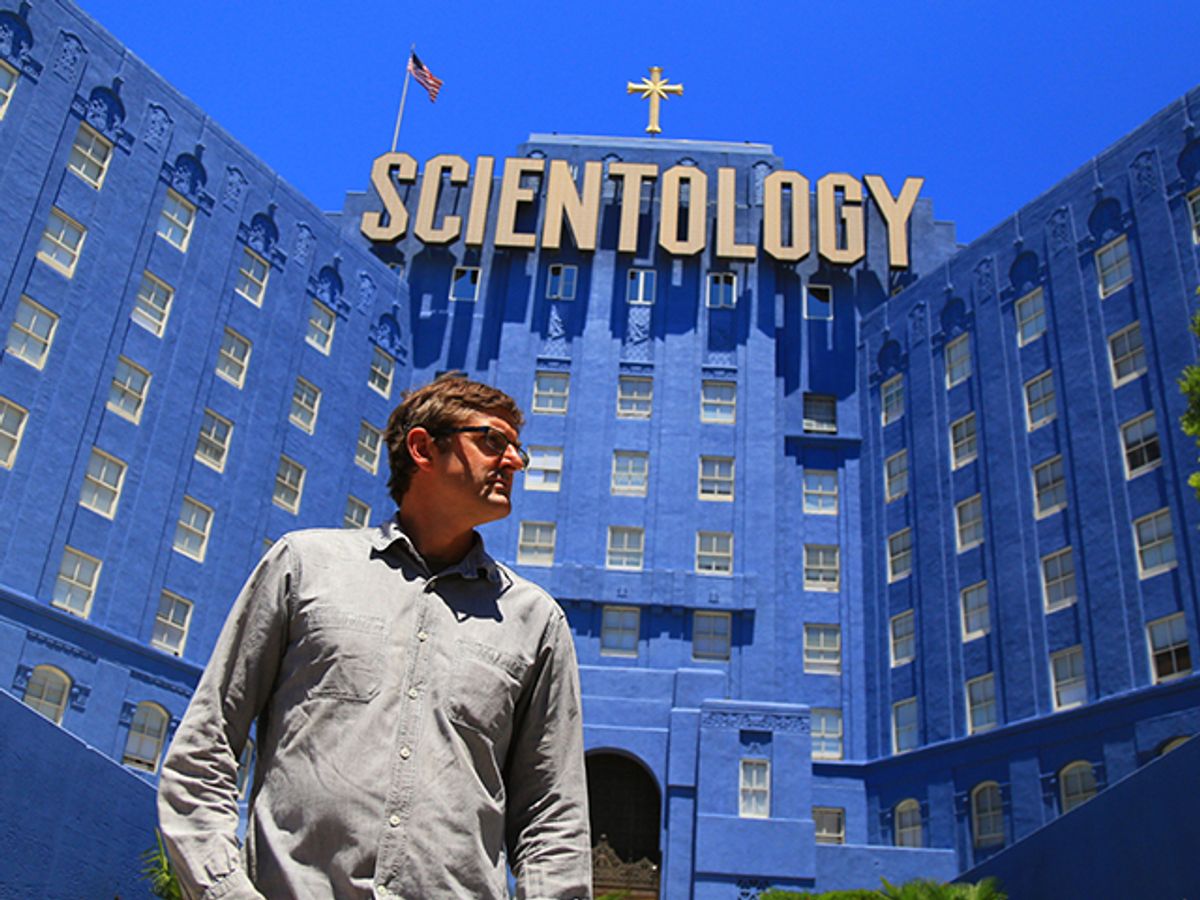

Louis Theroux, the British TV host and documentary filmmaker, made a movie about the Church of Scientology without quite knowing what he was in for. His perspective as faux-naive or actually naive outsider — “I prefer actually naive,” Theroux said when I put it that way — yields a number of unexpected benefits. His Scientology movie, which is puckishly if appropriately titled “My Scientology Movie,” makes a strange, compelling and often hilarious companion piece to more straightforward investigative works like Alex Gibney and Lawrence Wright’s “Going Clear,” the Emmy-winning HBO documentary from 2015.

Theroux stopped by Salon’s New York studio recently for a highly entertaining conversation about the making of “My Scientology Movie,” which to a significant degree is a movie about the making of itself. When I gently suggested that some people might call the film “meta,” Theroux embraced the term: “Yes, it is meta. That’s not a bad thing, is it?”

[jwplayer file="http://media.salon.com/2017/03/03.09.17-Thoreux-AOH-My-Scientology-Movie-Cutdown-V1.mp4" image="http://media.salon.com/2017/03/VIDEO_PHOTO_My-Scientology-Movie.jpg"][/jwplayer]

The only possible answer to that is “It depends,” but in this case Theroux’s movie-about-a-movie captures the atmosphere of unreality that permeates the Church of Scientology’s story in a way more normal journalism cannot duplicate. This is a religion founded by a science-fiction author in the middle of the last century that tries to balance outlandish claims about the nature of humanity and the universe with a commercial self-help enterprise that promises its adherents wealth and celebrity. A rambling, self-referential odyssey in which real events appear staged (and the other way around), hosted by a shambolic Englishman with a slightly startled demeanor — Theroux insists it’s not an act — is arguably the perfect instrument.

Early in “My Scientology Movie,” when Theroux is interviewing prominent Scientology defector Marty Rathbun in a Los Angeles hotel room, actress Paz de la Huerta stops by — in a bikini — to introduce herself. How and why that happened is not entirely clear, but Theroux swears he had never met her before and it wasn’t a setup. He jokes in the film that de la Huerta’s guest appearance might have been a “honey trap” set by the Scientology forces, but told me he doesn’t think that’s true. It was just one of those weird L.A. celebrity encounters partway between reality TV and David Lynch: De la Huerta saw a camera and perhaps a guy she recognized from TV, and thought it was worth a shot.

Theroux had no intention of making an anti-Scientology movie or an exposé; if you’ve seen his BBC documentaries, you already know his customary approach is more or less the opposite. In perhaps the best-known of those, “The Most Hated Family in America” from 2007, he did about as well as any secular outsider could do in presenting the worldview of the viciously anti-gay Westboro Baptist Church, a group so extreme it is shunned by most other Christian fundamentalists. (In 2011 Theroux made a follow-up special, “The Most Hated Family in America in Crisis,” which I haven’t seen.)

Theroux has also made films inside the world of American white supremacists and neo-Nazis (long before their rebranding as the “alt-right”), among the maximum-security inmates at San Quentin and in ultra-Zionist settlements on the West Bank. In all those cases and many others, he got some degree of access and cooperation, and had the experience common to all reporters: Once people start talking to you, they tell you everything, including the stuff they probably shouldn’t.

“I tend to think that people are best served in life by telling the truth and being open,” Theroux told me. “I mean, I suppose it’s in my interest to believe that because I trade on that. I tend to think that when we have communication with people you start to see things from their point of view a little bit, or at least you begin to understand why they do the things they do.”

He knew going in that Scientology would be different, although the nature of the challenge only became clear once he was making the film. “They view journalists and documentary-makers as the enemy,” he said. “I went into it with my eyes open knowing they weren’t going to give me access. I normally like to work with access, but the subject was so rich: It’s such a paragon of oddity and fundamentalism. You’ve got celebrity, Hollywood, and a kind of McDonald’s-style corporate entity, with a franchise-based system, attempting to roll out spiritual enlightenment.”

“My Scientology Movie,” which was directed by John Dower (Theroux is the writer and on-camera host), comprises at least three different films — and there’s a fourth happening contemporaneously, which we never get to see. There’s a more or less journalistic documentary about the secretive operations of the Church of Scientology, which sometimes deconstructs itself into a movie about the failed attempt to make such a documentary.

Then there are the dramatic recreations that Theroux and Rathbun commission in an effort to tell the Scientology story, auditioning and hiring actors to play David Miscavige, the church’s secretive leader, and top-gun Scientologist Tom Cruise. I know that sounds like a desperate postmodern gambit, but it pays hilarious and chilling dividends by turning episodes previously recounted only in disputed legal proceedings into confrontational Brechtian theater.

When I went through all those aspects of the film with Theroux, he pointed out that there’s another, less visible layer I hadn’t mentioned — the film Scientology was supposedly making about him. Every hostile encounter he has with a Scientologist or a church representative — and they’re all hostile — involves a silent onlooker with an iPhone or a video camera, filming Theroux while his crew is trying to shoot the movie.

Since constantly surveilling someone without their permission is a legally dubious activity at best (just ask our president!), the church had to come up with some rationale for this. “When pushed about why they were filming me,” Theroux said, the church “revealed in legal letters — because there was a protracted legal exchange while we were making the film — that they were just making a documentary about me. Which I love!”

Theroux expresses reasonable doubt about whether that reverse documentary will ever see the light of day. (I believe the church also claimed it was making a film about Alex Gibney, the director of “Going Clear.”) But this process of circular filmmaking enables the funniest, weirdest and most disarming scene in “My Scientology Movie,” when a woman Theroux describes as a Scientology "guard dog" tries to tell him he can’t film on a public road adjacent to one of the church’s California properties. He has a letter from the local sheriff saying he can, but of course she’s not interested. She keeps berating him and telling him to turn his cameras off, and Theroux steadfastly refuses to lose his temper, leading to a comical Mexican standoff: He'll stop filming her, he says, if she’ll stop filming him.

Despite the heated exchange, Theroux says he tried never to lose empathy for his opponent’s difficult position. If there’s a secret to his apparently offhand but strikingly effective documentary method, that may be it. To a loyal Scientologist like this woman, Theroux observed, he is a “suppressive person,” an enemy of the church. So any sort of contact with him is dangerous for her.

Even to be connected to a suppressive person makes you a potential trouble source, so it's almost like a contagion. I have a virus that she cannot catch. She's trying not to communicate with me; she just wants me to go away. We're all guilty of constructing our reality, and I think for me in that scene the challenge was to try to break through her constructed role and also not fall into it, not match her tone too much. I don't want to shout back. I want to go under her and build bridges. … There's a tendency in coverage of these subjects to fall into an us-against-them. You become a mirror image of what they're doing.

Theroux had encountered this woman before and knew her name; he had spoken to her former husband, who had left the church. “He talks about her as being a sensitive and kind person, someone whose personality has been channeled into this role of guard dog for the base. So I feel empathy for what she's being put through.”

Her anger and zeal, Theroux said, stemmed from the Scientology doctrine that “the future of humanity and civilization” is in the hands of its believers. Deluded as she may be, the stakes for her could not possibly be higher.

In a time of intense cultural and political division, that lesson in empathy may have much wider application. But as Theroux admits, it’s not easy to “build bridges” with someone who believes in things you think are false or deeply misguided, especially when they keep on telling you to shut up and go to hell.

Shares