Like many Southern cities, Clinton, Mississippi, bears the scars of American slavery. A road cutting through the city’s center marks a key route used by slave traders in the decades before the Civil War. Signs across town tell the story of a Reconstruction-era riot that claimed the lives of at least 30 African-Americans.

But, unlike many of its neighbors, Clinton is doing all it can to heal those scars through its public school system.

As the national discussion has shifted towards “school choice,” often a cover for charter schools and voucher programs, Clinton has moved in the opposite direction, towards working together and using public resources to give every student a high-quality education.

It all started with an innovative idea. In the early 1970s, Clinton began sending its kids to the same schools regardless of where they live. Instead of multiple elementary schools serving different neighborhoods, for example, there’s one citywide school for kindergarten and first grade, one for second and third grades, and so on. This fills Clinton’s classrooms with a mix of black and white students from all parts of town.

As schools nationwide are becoming increasingly resegregated, Clinton’s are thriving because of integration. Despite 40 percent of its students qualifying for free- or reduced-price lunch, the city’s high school graduation rate is substantially higher than the state and national averages. Teachers there have been ranked the best in the state.

Clinton stands in stark contrast with its neighbors. Last year, nearby Cleveland, Mississippi, finally gave up a five-decade legal battle with the federal government over integration. As of 2015, 179 U.S. school districts were involved in active desegregation cases, 44 of them in Mississippi.

The state capital, Jackson, is experimenting with charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately operated. Darlings of the “school choice” movement, charter schools are generally more racially segregated than traditional public schools. A study last year found that one in five charter schools in California, the state with the most charters, had a discriminatory admissions policy. On top of that, research continues to confirm that charter schools perform no better than traditional public schools.

In his February address to Congress, Donald Trump called education the “civil rights issue of our time.” There’s a grain of truth to that. Public schools are by some measures as segregated now as they were at the time of Brown v. Board of Education.

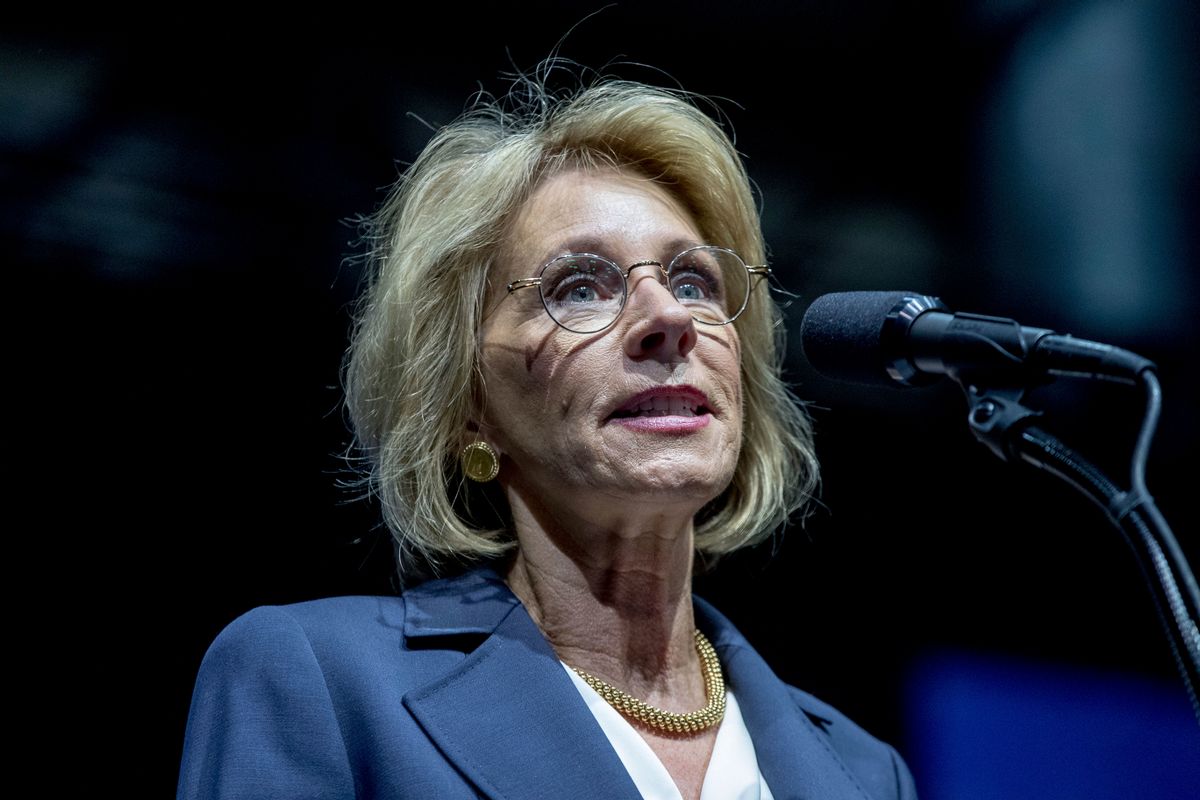

But the answer isn’t “school choice,” it’s better schools for all students. Trump’s push, along with that of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, for voucher programs, more charter schools, and less regulation is woefully misguided. It would send public money to private hands, with little to no accountability for students and parents.

As Clinton’s story shows, public schools designed to give all students a high quality education are powerful tools for addressing increasing economic and racial inequality. Leaving things up to the private market — DeVos’ definition of “school choice” — only makes things worse.

Every kid needs public investment, not a “choice” that only occasionally delivers.

Shares