Context 958, as he is known, spent much of his life doing backbreaking work and died in poverty and obscurity. His childhood included periods of malnutrition. He broke a rib at one point in his life and survived a concussion. He suffered from gout and a mouthful of dental diseases, including what must have been a painful, pus-ridden abscess, up to the day he died.

By modern standards, Context 958 would be considered a physical wreck for an otherwise fit man over the age of 40. But by the standards of his day, he was pretty much the average Joe of the medieval period’s poor, working class. His life ended sometime in the 1200s at a charitable hospital in Cambridge, England, his body dumped facedown into a pauper’s grave.

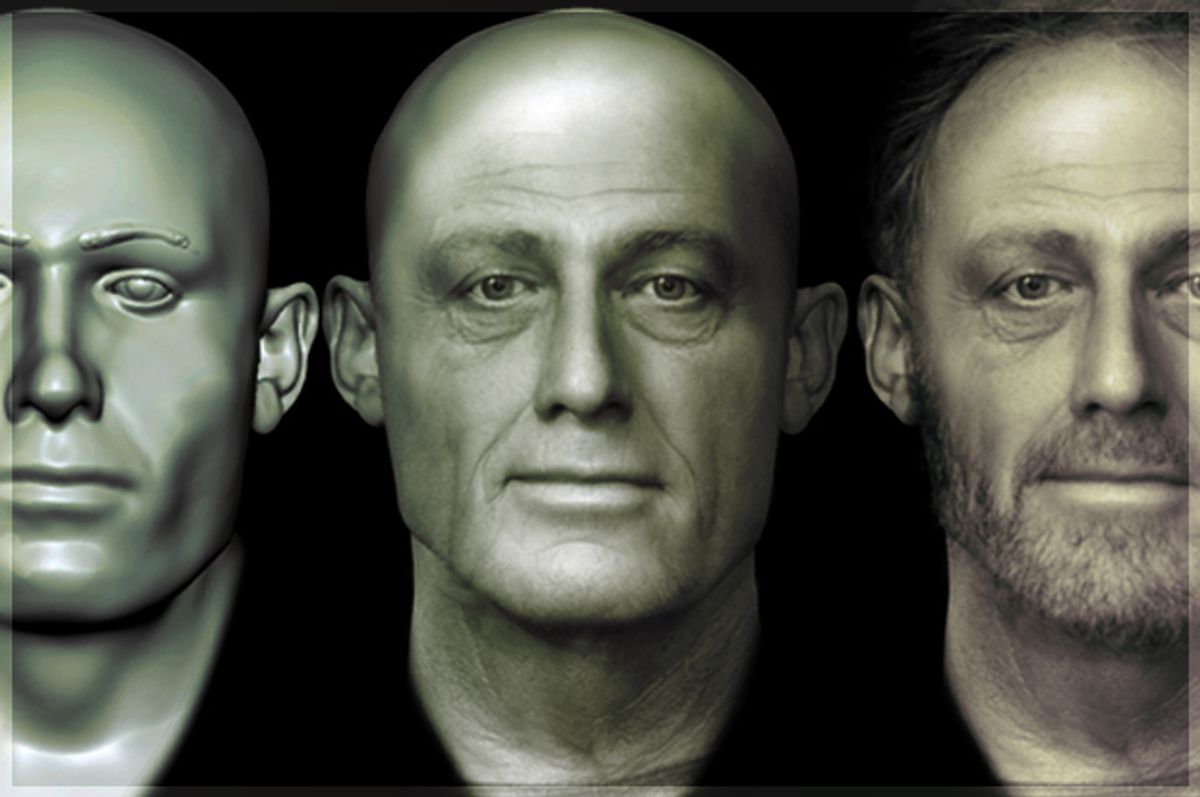

We know all of this about Context 958 — the name given him by a team of researchers who excavated a burial site between 2010 and 2012 — because his bones left a record of his life. But what did he look like?

Earlier this month, a team from the University of Cambridge gave us an answer after Context 958 became one of the few, out of history’s countless nobodies, to receive a digital three-dimensional makeover based on the precise measurements of his skull. The work is part of a larger project called After the Plague, an attempt to capture the life of England’s urban poor during the Middle Ages. Because impoverished people at the time weren’t taxed and didn’t own land, very little about them appears in official documents or historical texts.

This process, known as craniofacial reconstruction, has traditionally involved placing layers of wax onto a casting of the skull by someone knowledgeable in anatomy and skilled in art. These forensic sculptors re-create the human form taken from bone measurements, and the result is used as either a teaching aid (showing what a medieval pauper in England might have looked like) or to try to identify human remains in forensics investigations.

Today, thanks to the rapid advent of affordable 3-D digital rendering and printing technology, these experts are increasingly using advanced tools to make their work more easily distributed and duplicated. One of the gadgets that's helping researchers in this field uses haptic feedback (involving the sense of touch), which allows these artist-scientists to mold their three-dimensional renditions on a computer screen. (An example of haptic feedback is when a smartphone vibrates when a user presses a button on a touchscreen.) This data can also be easily transmitted to a 3-D printer allowing for automatic replication.

These tools might not be as high-tech as the Angelatron, the fictional holographic projector from the television series “Bones,” but they’re helping forensic anthropologists generate super-realistic digital renderings like that of Context 958.

A 2006 blind study conducted by Scotland’s University of Dundee and the FBI showed that such digital rendering could produce strikingly accurate and identifiable faces. With the skull’s dimensions and an understanding of facial muscle anatomy, researchers can gain a strong sense about how a face on a particular skull would look, even if the images are less accurate about the tip of the nose, the shape of the ears and the hairline.

The research shows the potential for this technology to supplement the more standard and traditional practice of building models out of wax.

Some re-creations, like Context 958’s, reflect a certain degree of subjectivity, according to Christopher Rynn, a lecturer at the University of Dundee’s Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification, who participated in the 2006 study.

“A historical or archaeological facial reconstruction is more to bring a character to life, to enable interaction with a person from the past, so we can use more artistic license to put more detail into things such as surface textures, facial expressions, wrinkles, hair, etc.," Rynn told Salon via email.

A good example of how digital technology can factor into historical reconstruction can be found with the fate of King Richard III, who died in battle in 1485. The body of the notorious ruler was lost to history until the remains were discovered in 2012 under a parking lot in Leicester. His head and face were physically reconstructed in 2013 by researchers at the University of Leicester based on measurements of the skull, with finer details taken from paintings made during and after his death by artists who themselves were likely taking artistic license. In the paintings, however, the king’s severe scoliosis isn't apparent. His condition was hinted at in other sources, like William Shakespeare's depictions of him in "Richard III." His scoliosis was ultimately confirmed in 2015 when the university researchers scanned his vertebrae and printed a 3-D reconstruction of his spinal column.

Because Context 958 was a poor commoner, precise details would have to be drawn from general knowledge of how a man of his age and stature might have looked at that time.

This artistic license works for a museum, but it doesn’t work for the purposes of solving crimes or identifying crime victims from skeletal remains, which is why facial reconstruction for investigative purposes tends to have less detail than the historical or archaeological renderings. These features "would be from material found at the scene, or made as vague as possible if no information was available,” Rynn wrote. “Often the top of the head is cropped from a forensic image if we cannot estimate the hairline/hairstyle.”

Context 958 might not have looked exactly like his 3-D avatar, but after being locked in the ground for 700 years, he’s been digitally revived as a witness to history, offering us a rare glimpse into the hard life of a medieval pauper whose face will exist online indefinitely.

Shares