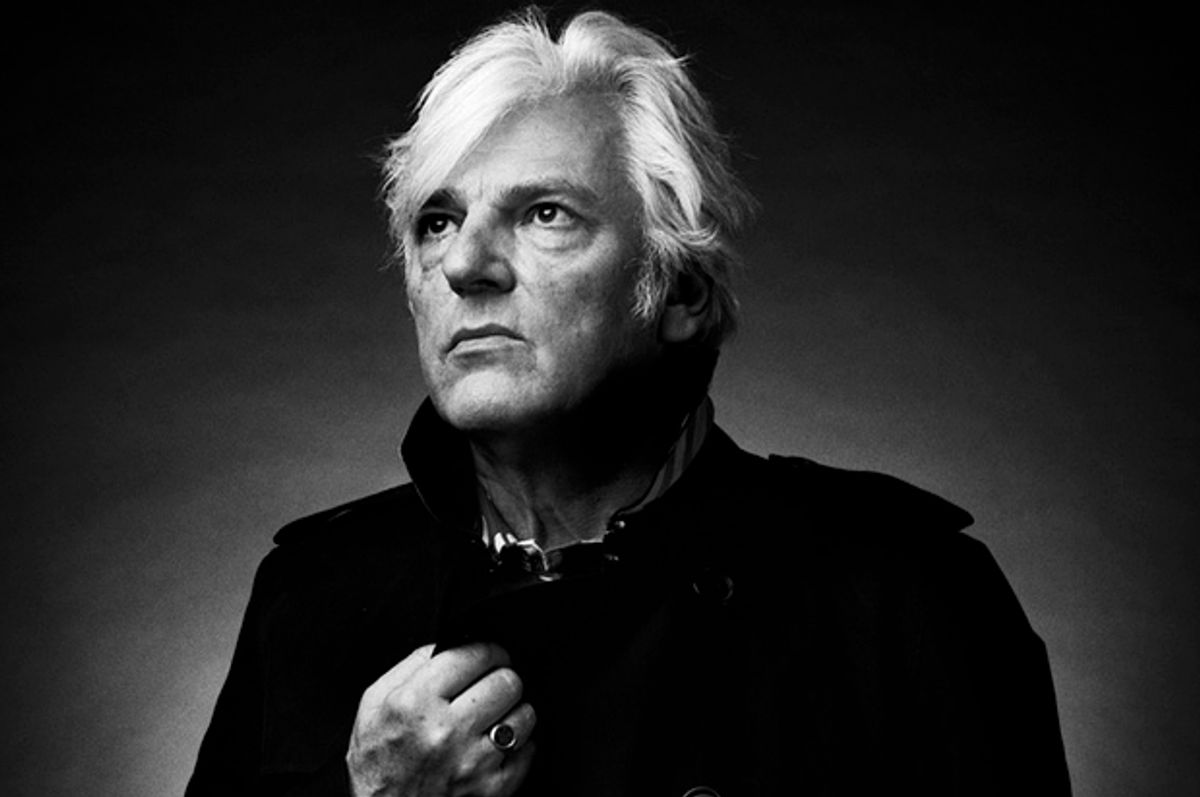

Robyn Hitchcock needs no introduction. However, the former leader of influential '70s neo-psych-punk act the Soft Boys — and the purveyor of a long and winding solo career — is helpfully providing a peek into his inventive, erudite musical world with a self-titled studio album. Released April 21, "Robyn Hitchcock" is more rock 'n' roll-oriented than Hitchcock's recent work. "Mad Shelley's Letterbox" and "Virginia Woolf" feature twin attacks of ringing, psychedelic-tinged guitars, while "Detective Mindhorn" and "I Want to Tell You About What I Want" are classic examples of compact, Hitchcockian jangle-pop.

"Robyn Hitchcock" came out of Hitchcock's recent peripatetic lifestyle. The musician wrote the songs on the record while "visiting two or three places at once and touring," as he puts it. "It was like a one-man diaspora, really." In the past few years, he lived on the Isle of Wight for a spell, and also followed his partner, Emma Swift, as she moved around from Nashville to Sydney, Australia. "I found myself lurching between Sydney and the Isle of Wight — but making Nashville into my base when I was in the States, with the intention to move here," he says. "And then, eventually, I did."

"Robyn Hitchcock" was recorded in this new hometown of Nashville with local players, although the most country-sounding song on the album, "I Pray When I'm Drunk," coalesced in Norway. However, references to travel and modes of transportation crop up throughout — Hitchcock penned the lyrics of "Detective Mindhorn" while on the Tube in London, while the daydream-textured "Raymond and the Wires" is a reminiscence of a day out he had with his late father.

The video for this song, which Salon is exclusively premiering, is comprised of "a collage of years and Hitchcocks," the musician says. The clip features archival family home movies and footage of current-day Hitchcock cobbled together by director Jeremy Dylan.

"I'm singing the song on a tram in Melbourne, Australia, about a trolleybus ride I took with my late father Raymond in Reading, England, in 1964," Hitchcock says. "In these clips, Raymond — resplendent in early '70s porno moustache — is younger than the present-day me is now. My current self is also in there perving over some beautiful vintage trams in San Francisco.

"There's a glimpse of 13- year-old me stepping out of a boat to greet my sister Fleur, who now, in later life, is an author and incidentally supplied Jeremy with the old family film," Hitchcock adds. "And 39-year-old me peers for a second from a weeping elm tree at Raymond's wake in 1992. His favorite folk band, the Yetties from the West of England, gave us all a free show — what a night!"

The cumulative effect, according to Dylan, "was to hit a kind of jittery home movie feel across the whole clip, reflecting the emotional continuity between Robyn’s country of origin, his two adopted home countries of recent years and the memories of his father Raymond he still carries with him." Hitchock adds that his father "liked a nice tune. This would probably have embarrassed him, given what a distant English family we were. But his spirit loves acknowledgement, I like to think — and I'm sure he lives through me as fully as any ghost."

[jwplayer file="http://media.salon.com/2017/04/4.7.17-RobynHitchcock-HDv01.mp4" image="http://media.salon.com/2017/04/RobynHitcockVIDEO.png"][/jwplayer]

Separately, Hitchcock checked in with Salon via phone from a San Antonio hotel room, where he was trying to get the coffeemaker to cooperate. The conversation immediately jumps to his current tour: Hitchcock is opening for the Psychedelic Furs — a full-circle moment, as the Soft Boys opened for the group back in 1980 — although he quips he's "being paid much better these days."

"Time has rather telescoped us together," Hitchcock adds. "In those days, we were very different sorts of creatures. I'm a big fan of Richard Butler's singing, and a lot of the songs, you know, the music. There's something about the way the Furs go that I've just always been very attracted to. I don't really know anything else like it."

There's a melancholy tone to even some of the more chipper songs, and I've always loved the band because of that.

You're right, it's kind of aggressive, but melancholy at the same time. Some of the music sounds very '80s, because they had very '80s arrangements, and they're still attached to the songs. And maybe it sounds a bit less '80s than when I saw them in the early 2000s. But that's time for you.

When I first saw them, it was the beginning of the '80s, so they didn't even really sound '80s. They had the snare drum you could land a plane on, because their producer, Steve Lilywhite, was one of the first people who came up with that. And we couldn't afford snare drums that you could land a plane on. Our snare drums you could just about get a helicopter on, if you were lucky. They had much less surface area.

But by the mid-'80s, everybody had it. It was cheap. You couldn't make a record without a version of that digital drum sound. I think now their drums sound fairly organic, actually. That's a good point.

I think you're right. I saw that 2002 tour you mentioned. Your hair was getting blown back. There was some grit going on, some urgency.

In 2002, the '80s were not so far away. There wouldn't have been many people who were nostalgic. Most people who were coming of age in the '80s would barely be feeling any older. Ten years after that, you would be getting all of that — people wanting to re-live Melanie Griffith, shoulder pads, exploded hair and wedge-shaped haircuts, and all the digital patina that was sort of digitally shaken over everything. It seems very synthetic now. The '70s seem very organic. Seventies nostalgia is still going. I suppose that will fade in another 10 years, maybe. But the people who were born in the '70s, or started grooving in the '70s, still love it.

I feel like the internet really makes nostalgia last longer, too, if that makes any sense.

You mean, because everything is accessible on YouTube or 'cause people keep going on about it on Twitter?

Both, actually. Definitely Twitter, and there's such a market for anniversary pieces. And the stuff that surfaces on YouTube is just mind blowing.

Well, again, it seems like a lot of people who were kind of squandering their looks on mullets and shoulder pads — I mean, me included. I didn't have the shoulder pads, but there's certainly a fair bit of me getting mulleted. And I remember back then — because, essentially, I'm a '60s creature — my partner of the time, and people like that, were keen to get me topiaried into a mullet. To get a look that was '80s-y, and to have trousers that were baggier at the top and tighter at the bottom, and all that stuff. Which was really anathema to me as an old hippie. I'm actually happier with the look I had in Soft Boys days, with straight hair with a parting and tight trousers. I thought it was straight from the '60s, but it was more timeless.

You're right, it isn't as dated. I just pulled up a picture now.

Yeah, I sort of started to get dated when I let myself succumb to the '80s, and sort of fit in with it more. I know I seemed like a throwback at the time. That's the thing with time: You don't really know how you're going to fit in with it until later.

It's absolutely true. You never know how your legacy is looked at, or how something at the time you make will be perceived five, ten years down the line.

Right. It may be that there will be a thousand-year mullet Reich about to start now, and everyone who had a mullet and wore '80s clothes will seem familiar, and make sense to the people of the future. I think it's unlikely, but it's possible.

God help us all.

Yes, hopefully she will.

Producer Brendan Benson asked you to make a record like the Soft Boys. Is that true, and what was your reaction to that?

Yeah. He offered to produce me, and he said "Could you make a record like you did in the Soft Boys?" And I said "Well, the songs are not fueled by the same kind of anger as I had at 25," and he said "Well, they never struck me as particularly angry." But I think what he was talking about was the lineup — the two guitars, bass, drums, harmonies — rather than the emotional nutrients. And also rather than the funny time signatures that we had in the early Soft Boys stuff. Although he did like that. But he was thinking of the sound, really.

And that sound, it's a descendant of Buddy Holly. It goes Buddy Holly, the Beatles, the Velvet Underground, Big Star, the Soft Boys and on. So, yes, it was good. He's got lots of guitars in his studio, and we were able to make such a record.

What did the Nashville musicians you used bring to the music?

They're very good. They're quick. They're not country, specifically. They know all country, because they would've played quite a few sessions in that world, but they're just as at home playing rock. [Jon] Radford, the drummer, if you listen, there's some songs where he's playing like Keith Moon. But he'll find some very intricate part, and then he can repeat it perfectly. They also figure things out really fast. You may or may not need a rehearsal. We rehearsed some songs, but not others.

Wow.

And I'm glad we did rehearse, because it did give us a chance to play organically, as a group, even once or twice before the session started. But you bring the song in, and go through the chords, and they get the chart. And then they talk to Brendan a bit about arrangements and talk to me a bit about what's gonna work. This is the rhythm section, particularly. But they're just so alive, so fast.

In Britain, you know, you had to have a couple of weeks' rehearsal with everybody to bring them in the material and yourself in to make it all organic. But these two — they're both Jons with no "h"s, Jon Radford and Jon Estes — they work together a lot anyway. And Annie McCue, playing the guitar, she's Australian. She's lived in Nashville a long time. Annie and I ran through a few songs at home before going and playing them in with the others.

But, overall, it was fast, and it was quick, and it was alive straight away. And I love that. It was as if I had a band that I've been touring with. There was a sort of understanding. I love Estes' bass lines. He's a bit of a McCartney: He can be really straight ahead, and then he'll just start walking around in these little melodic trails. Yeah, it's good.

It does seem like recording in Nashville, there's just this live, vibrant energy. It's very interesting.

I think there is. I mean, the one time I've recorded before was with Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings, but that was mostly acoustic. I don't know if you've heard that record, it was done about a dozen years ago, called "Spooked." That's me in a Gil and Dave sandwich.

This one is a rock record — or as rock as I get. Psychedelic pop, or whatever you want to call it. In a way, I'm not really a rock artist, because I go back to the end of the days of the beat groups, where you had two guitars, bass, drums and harmonies. And all that was kind of knocked away by Jimi Hendrix and Cream and the power trio. The rhythm guitar disappeared.

[On this record] Annie and I are playing rhythm or lead. It's just meant to be parallel guitar tracks, like it was in the Soft Boys — which in turn is descended from Captain Beefheart, I suppose, and the Velvet Underground, a bit. It's using two electric guitars in the best way I think you can use them. Neither one really dominates, and they don't muffle the rhythm section, nor are they obliterated by the rhythm section, the way rhythm sections ousted guitars in the '80s.

[Back then] the guitars all became these little sort of pingy things that happened on the left and right. And the snare drum, you know, sort of strode to the center like a mammoth, and sort of said [assumes low, growling voice] "Here I am" — you know, beating its chest, gouging the ice with its tusks. It's not really like that. The drum sound has settled down now. In a way, you have a sound more like the old beat groups' sounds.

"I Pray When I'm Drunk" reminded me a lot of Johnny Cash when I was listening to it. I don't know if that's just your delivery, or what.

I sing it in that way. I have to stop myself doing the full Cash on it. It's a song I wrote for Johnny Cash, but he's no longer there, so I have to sing it myself. But the backing is actually more like "Revolver" Beatles, to me. It's like dropping Johnny Cash over "Revolver." And with the pedal steel, I like to imagine that it's something off "Younger Than Yesterday" or "Sweetheart of the Rodeo" or something, you know, [by] The Byrds. I'm kind of connecting with the country-ish stuff that I know, but I'm not going George Jones or Loretta Lynn or the full Willie Nelson or anything.

Nashville is definitely more of a diverse music city now, too.

Oh, yes. Definitely. Certainly where I am, East Nashville, it's a colony. It's a neighborhood. You will run into people in the bar who are playing on your session the next day, or at the coffee shop. It's that close. I don't think I ever go out without running into somebody I know. I lived in West London for 18 years. Some days I'd see somebody; some days I wouldn't. Mostly you were just in a lake of strangers.

And that's a weird experience. There's pros and cons to both of it.

Well, it is, because a smaller society is more enclosed, it's more like a village. So if people were to take against you, or if you were to make an enemy, it would be harder to get away from. Or if you developed a bad reputation, it would follow you at close range. It would sit there next to you at the bar or at the table. It wouldn't be so good. London is more anonymous, yeah. Your sins can be washed away by the crowd. Or people's idea of your sins. I don't know, I mean, Nashville's not that small. I guess it's got a million inhabitants. It's not like living on the Isle of Wight, or living in Hampshire, or one of those places that I grew up in.

This far into your career, why call this record "Robyn Hitchcock"?

It's the sum of everything I am and everything I've done, you know. People would often say "Where do I start listening to your songs? Your music, it's gone on for 40 years, now!" And I didn't write these songs and think to myself "Right, this is gonna be 'Robyn Hitchcock.'" But actually listening to it, it's a fairly good way of describing it.

If you give an album a title otherwise, it in some way refers to the title. But, actually, these songs are just me. It's what I'm made of. And, of course, what I'm made of is other people. Most of the songs are about people — living or dead, fictitious or real — that I've been involved with, I suppose. By the theory one is actually made of other people. Your personality, your fixations and everything, are all about others. You're the building blocks of a person, or other people. They could be sub-personalities, but I don't know.

So I thought that was like "There they are." They all amount to me, in a way. In a way, it's a piece of colossal egotism. [Laughs.] But I'm not saying I am everybody. I'm just saying that these people are the components of me. I mean, I haven't mentioned everyone who is a component of me, by any means. If this one goes well, I'll do "Robyn Hitchcock II: They're Back, and There's More of Them."

So I thought it would be a good way, rather than starting your career with your name, I sort of finish it. Who knows what will be around? I don't know if I'll make any more records or not. But I just thought, you know: "Here I am, I'll plant the flag." The map of the future is unclear, but I thought that naming this record "Robyn Hitchcock" would make it into a calling card — a career summary, if you will. If you want to hear what I am, this is it. If you like this, my other records might suit you. If you don't, then I'm not for you.

Shares