On Nov. 19, 1978, a small Guyanese military detachment marched through their South American country's foreboding jungle into the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, an American farming community known as Jonestown. The troops, accompanied by 20 teenaged trainees, feared they'd find themselves in a firefight with the followers of the Rev. Jim Jones, who established the 3,800-acre agricultural project in 1974 with the blessings of the Guyanese government. What the Guyanese Defense Forces found there, however, had them longing for a shootout instead.

The grounds of the Jonestown compound were covered in corpses. The bodies were already bloated from the jungle's intense heat and humidity, even though Jones and his followers had been dead for barely a day. A handful of the Peoples Temple members, including Jones himself, had been shot. The rest of the 900-odd people who died there had killed themselves by drinking a grape-flavored drink spiked with cyanide.

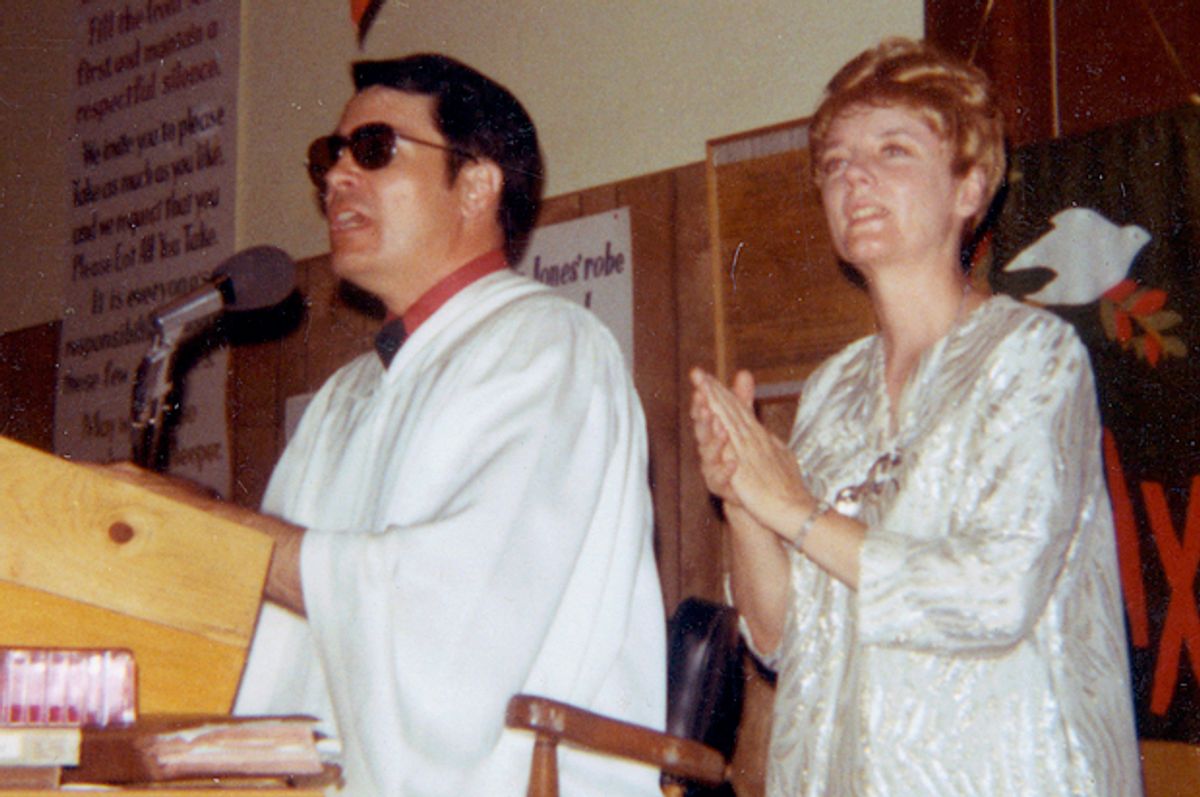

The press called the tragedy the "Jonestown Massacre," and they spun it as a cautionary tale of a Svengali-like Jones — always shown wearing oversized shades and looking like a brooding Elvis impersonator — exerting total control over a legion of brainwashed followers who would do anything at his command. They literally "drank the Kool-Aid," spawning a trope that has lingered in American culture long after its origins have been forgotten.

"As I started to poke around, first thing I found out was that it wasn't Kool-Aid," author Jeff Guinn said in an interview, recalling the research for his new book, "The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple." Indeed it wasn't. The poison-delivery system at Jonestown on Nov. 18, 1978, was actually Flavor-Aid, a discount Kool-Aid knockoff.

"A lot of the people who died that day didn't drink the poison voluntarily," Guinn added. The Jonestown story, he said, "is once again a reminder that too often instead of actual history, we prefer mythology. It's easier to believe that over 900 people died in Jonestown, including about 300 innocent kids, because they were all foolhardy and stupid, and trusted somebody who clearly they should not have trusted. The tragedy goes greater when you realize why they were there and how, in the end, they were willing to give up their lives, even though it wasn't because they believed in Jim Jones anymore, but because they thought there was just nothing else for them."

When Guinn isn't writing fictional Westerns, the Texas native writes in-depth biographies exploring the facts behind the myths surrounding such violent American figures as Wyatt Earp or Bonnie and Clyde. "The Road to Jonestown" is Guinn's follow-up to his acclaimed 2013 "Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson." Following a book about Manson with one on Jim Jones might seem a natural progression; Guinn sees any similarities between the two cult leaders as mostly superficial.

"Comparing Charlie Manson to Jim Jones is like comparing Mickey Mouse to Machiavelli," Guinn said. "Manson at his best could only attract a couple dozen drug-addled kids, and even then he couldn't hold onto most of them very long.

"Jim Jones was who Charlie Manson wanted to be," he went on. "Someone with thousands of followers; someone with real political and cultural influence."

Jones took an unlikely path to prominence. He was a white minister to a mostly African-American congregation in 1950s Indianapolis, a Midwestern city with very Southern policies toward race. As a voice for the powerless, Jones became a driving force for integration in the Indiana capital by 1960.

Jones' successes continued when he moved the Peoples Temple to Northern California in the mid-1960s, after an Esquire article convinced him that Mendocino County was where he and his church could survive the nuclear Armageddon he had prophesied. By 1976, Peoples Temple had helped mobilize enough votes to make George Moscone the mayor of San Francisco, transforming what was then a relatively conservative city dominated by business interests and Democratic machine politics into the liberal bastion we know today. But only two years after reaching his zenith of prestige and influence, Jones and his core followers would be lying dead in the jungle.

There were early warning signs, such as Jones' childhood penchant for staging funerals for roadkill, or his comfort with faked faith-healings on the rural revival circuit. But Guinn never lets the more lurid aspects of the Peoples Temple story overwhelm the narrative. In taking this measured approach, Guinn gives us a better understanding of why so many stayed with the Peoples Temple even after Jones became increasingly controlling and abusive as the 1970s went on.

"If Jim Jones had been killed in a car wreck on his way moving from Indiana to California, he would be remembered as one of the great leaders in the early civil rights movement," Guinn said, "and he'd deserve to be remembered this way.

"I mean, you have people walking around San Francisco who say they wouldn't be alive today without Peoples Temple and their drug programs," Guinn said. "Peoples Temple really did do all these fine things.

"One of the surprising things to me when I started writing this book, and meeting Temple survivors, is that so many of them are really intelligent, capable people," Guinn explained. While the handful of young people who followed Manson hoped to rule the world by Charlie's side after a race war called Helter Skelter, Jones was the rare demagogue who attracted followers by appealing to their better angels.

"Nobody joined Peoples Temple to get anything," Guinn says. "They were willing to give up material things to try to make it a better world for everybody, and that, to me, is the definition of tragedy."

Guinn found himself even more awed by what the Peoples Temple had achieved after he and five other men hacked through two miles of "triple-canopy jungle" with machetes to get to the Jonestown site in Guyana.

"There's snakes everywhere, and all kinds of biting insects," Guinn recalled. "You can hear animals rustling just out of sight, and the animals can include big cats. It's a dangerous place." Despite these tremendous obstacles, Jones was able to motivate his mostly African-American followers from the forgotten neighborhoods of Los Angeles and San Francisco "who'd never so much as mowed a lawn" to "carve out an almost self-sustaining farm out of this place."

It's a "staggering" achievement, Guinn observed, one that the Guyanese government has not come close to replicating, although it has tried several times over the years.

Whether Jones was always a disordered and dangerous personality, or was more like a well-meaning person gradually overtaken by hubris and paranoia, can be debated but never known. At some point during the 1970s, Guinn says that Jones abandoned being a shepherd to his flock, and began "to think of himself as a general," and his followers as "troops or soldiers."

"Jim Jones wanted to make one final great statement that would make his name live in history," Guinn explained. "If that meant the soldiers had to be sacrificed for that victory, he was willing to do it. Of course, I hope he's remembered in a way he never would have wanted."

Although the story of Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple is deeper than the simplified mythic version of it that haunts the American zeitgeist, the real story of Jonestown still holds lessons for dealing with demagogues in 2017.

"Anytime a leader, or someone presenting himself or herself as a leader, tries to first define the world into us and everyone who's against us," Guinn said, "that is a huge sign of danger, and everybody ought to back away.

We have demagogues today as we've had in 1978, and have had them through recorded civilization," Guinn reflected. "At some point I hope our culture starts making people who want to be leaders focus a little bit more on the facts, and a little less on whatever is convenient to try and make people believe something that is not necessarily true."

Shares