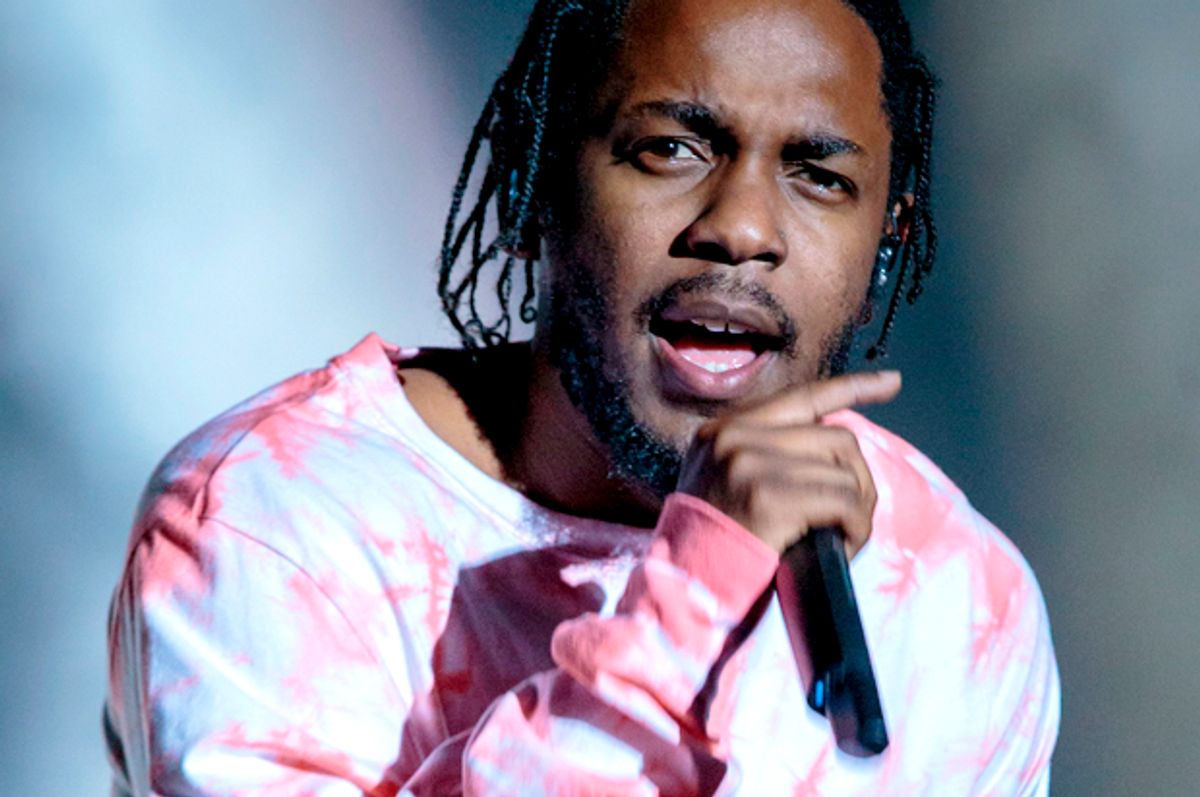

Hasty reaction is probably a sin — at least, or especially, when it comes to Kendrick Lamar. Lamar is the most perfect rapper (dead or alive) — his flow is flawless, everything else (his lyrics and arrangements, the samples he chooses) is unparalleled in its combination of grandness and precision — and, as such, his work deserves to be analyzed in college courses, not in quick blog posts. (I repent.) He’s also an artist bent on reminding his fans of his fallibility — which by secular standards is modest — and, as such, of all of our fallibility.

All of this was true on Lamar's last big album, “To Pimp a Butterfly,” but it is redoubled on his latest album, “DAMN.” “DAMN.” is a sequel to “TPAB” in more than just chronology. Whereas Lamar’s major label debut, “good kid/m.A.A.d City,” was a complex hip-hop origin story, “TPAB” and “DAMN.” are sweeping epics about fame, race, class, religion and where Lamar fits in.

But if “TPAB” looked within to cast out, “DAMN.” is doing the inverse. “‘To Pimp a Butterfly’ was addressing the problem,” Lamar told T Magazine, referring to the racial tension that was coming to a head at the time of the album’s release. “I’m in a space now where I’m not addressing the problem anymore.”

What Lamar claims to be addressing now is God. “Nobody speaks on it because it’s almost in conflict with what’s going on in the world when you talk about politics and government and the system,” he said.

Never mind that God hasn’t been so well represented in popular art since 1512, showing up in the biggest contemporary music (Chance the Rapper’s “Coloring Book,” Kanye West’s “Ultralight Beam”) and television (“The Young Pope,” “The Leftovers”). What Lamar has to say about the King of Kings and the way he depicts Him stands apart from other modern artists’ reckoning with religion — chiefly because of the intensity and direction of his reckoning.

On “DAMN.,” Lamar does not ask whether there is a God, nor does he proselytize on behalf of one; he does not take us to church with gospel samples or try to invoke God’s sublimity with a beat drop. Rather, “DAMN.” is a curious confessional — for Lamar and for America. Lamar’s faith is sure but his sanctity is not. “Is it wickedness?” a holy-sounding voice intones on the first line of the album. “Is it weakness?/ You decide./ Are we going to live or die?”

These questions of judgement are aimed at America as much as they are at Lamar. Lamar’s first verse follows, in the form of a spoken dream-like story. In it, Lamar describes trying to help a blind woman on the street. When he says "Hello, ma'am, can I be of any assistance? It seems to me that you have lost something. I would like to help you find it," she replies "Oh yes, you have lost something. You've lost your life," and shoots him.

The sequence is a metaphor for the sample that follows: a tape of the Fox News commentator Eric Bolling angrily misinterpreting Lamar’s black empowerment song “Alright” as a statement of police opposition. “To Pimp a Buttefly” was meant to help America understand its problem with race. But the people who most needed the help — people who are figuratively blind to the problem — take the offering as a declaration of war.

Fox News is a recurring target on “DAMN.” In the same clip in which Bolling referenced “Alright,” Geraldo Rivera weighed in: “This is why I say that hip hop has done more damage to young African-Americans than racism in recent years.” Lamar samples that line, too. But rather than diss Geraldo, who is completely unaware of the grotesque irony of the statement, Lamar explains: “Somebody tell Geraldo this nigga got some ambition/ I'm not a politician, I'm not 'bout a religion/ I'm a Israelite, don't call me Black no mo’.”

Modern politics inform the hazy, at times noirish tone of “DAMN.” and are the backdrop to the bigger questions being asked. “TPAB” imagined black America rising up; “DAMN.” is reflecting on how malevolent forces prevailed. Perhaps not surprisingly, Donald Trump is also referenced on the album — which leads Lamar to ask, “But is America honest or do we bask in sin?” In other words, Am I the problem or is it you?

For most of Lamar’s listeners, such questions have obvious answers. But the album is terse, with thoughts stopping mid-sentence (“It's not a place/ This country is to be a sound of drum and bass/ You close your eyes to look ar—” Bono sings on “XXX.”), bleeding into the next, and circling all the way around. Lamar is connecting a lot of big ideas. On first blush, he does so beautifully; but it will take time for the album’s more nuanced brilliances to become clear.

Shares