From the very beginning of “Citizen Jane: Battle for the City,” a thought-provoking new documentary from director Matt Tyrnauer (“Valentino: The Last Emperor”), the city, in this case New York, is personal and metonymic. The debate over how to manage its density, poverty and infrastructure sets the stage for an epic struggle between journalist-activist Jane Jacobs and midcentury “power broker” and “master builder” Robert Moses.

The film captures a bygone New York with a certain hard-hitting, evocative nostalgia. While Moses was tearing down tenements and building projects, Jacobs organized grassroots efforts to protect the sanctity of neighborhoods and small businesses. Taken together, their diametrically opposed visions, one of buildings, highways and traffic patterns, the other of human beings and vibrant street life, form yet a third possible theory of how to maintain the spirit of New York and its diversity amid the onslaught of gentrification and all that it entails.

On one level, it’s easy to vilify Robert Moses as the the Goliath to Jacob’s David, and to categorize his life’s work the way one might a crazed Civil War surgeon, lacking subtlety and amputating limbs to stave off the onset of gangrene. In an effort to impose his myopic version of progress onto a city, he forgot to take into account the people who grew up, worked and died there. I’d add that, on some level, as a Jewish person, Moses wanted to create a promised land where he wasn’t the outsider but the accepted king. Also Tyrnauer makes the point that Moses began his professional life as a progressive who wanted to improve the conditions of extreme poverty and inequality that beset large swaths of the population who were living in substandard conditions.

Looking at the images of people in the tenements, it’s hard not to feel the need to do something. The question the film asks isn’t so much who’s the Mary and who’s the Rhoda in the Jacobs-Moses question, but what’s next. What do we do when both social experiments need a re-examination?

“I’m a modernism groupie,” Tyrnauer tells me. “I’m a fan of the theorists that Jane said were responsible for the ‘sacking of cities.’ It just didn’t work. The architects and city planners wanted to wipe the slate clean and rebuild. This idea was great for cities but not so great for the people who actually lived in them. Robert Moses and these guys thought they were doing right but they went astray.”

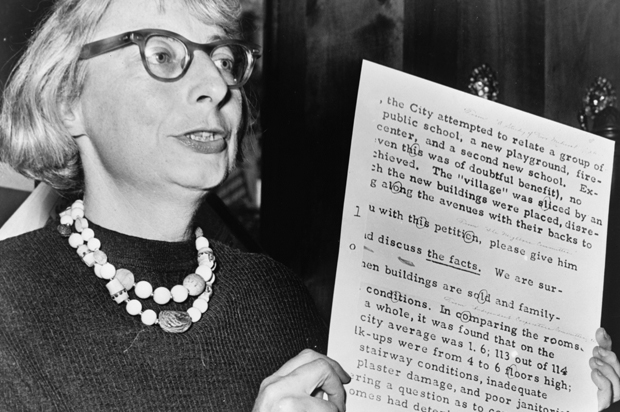

In the film, Jacobs, on the other hand, emerges an urbanist folk hero who understood on an innate level that the value of any city is its people, its public spaces and the street. A brilliant wordsmith in outstanding eyewear, she captures the essence of both neighborhoods and their inhabitants in her writing and wholeheartedly fights for their survival with everything she’s got, even when her detractors called her a “militant dame” and a “housewife.” Though all her ideas didn’t come to fruition, her spirit and her message are infectious: Give the people what they want — “people” being either a sort of Arthur Miller “View from the Bridge” utopian vision of working-class New York or a pack of West Village mothers who fought to keep Moses from turning Washington Square Park into a four-lane roadway that would connect Fifth Avenue with West Broadway. They won.

“In ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities,’ Jacobs writes a compelling theory that turns out to be true which is that cities are organized from the bottom up rather than the top down,” Tyrnauer continues. “This was a radical idea in the ’50s and ’60s. Jacobs called these guys out. If it had all been done from a human perspective, a lot less damage would ultimately have been done.”

Tyrnauer is clear on the point that Jacobs, her book and even his film don’t offer a cookie-cutter solution for how to fix the problems still facing large cities, though all three clearly indicate the point where urban planning went horribly wrong. “Citizen Jane” highlights the fact that for guys like Moses, the concept of urban renewal became synonymous with removal of people of color who were put at the margins of the city and denied the vital aspects of life that people need to thrive and prosper.

“The so-called ghettos where minorities are forced to live is a huge black mark on American history and a huge part of this story,” Tyrnauer says when I mention the fact that Jacobs has been criticized for her omission of race from the narrative. “When Jacobs was writing ‘Death and Life,’ she was writing a book on cities, not writing a book on race. She was championing the city as a place for everyone.”

What’s remarkable here, of course, is that New York City was never a place for everyone, least of all the urban poor who, before Moses and his band of highway-happy “pseudoscientists” arrived on the scene, lived in disease-ridden conditions in tenements and then were relocated in favor of some failed, racist vision of urban renewal. Meanwhile, the concept of diversity in “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” is architectural and an art form; Jacobs espoused mixed-age buildings to allow for different uses and sidewalk traffic where people could all commingle and thus look out for one another and maintain the safety and liveliness of the neighborhood. In her mind, diversity was busy and busy was good, whereas Moses seemed to favor some sort of empty, modernist dreamscape for cars.

“She would have fought gentrification today,” Tyrnauer adds sadly. “She called it ‘over success.’ Interestingly, in an attempt to preserve the neighborhood, she fought to save SoHo from the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which she did because she wanted to save the neighborhood, even though later it became overly gentrified. I think if she saw all the condos being built she would have recommended that residents change the zoning laws to preserve the artistic character.”

Whether co-designed populism seems possible or one woman’s idealistic pipe dream, what remains essential to appreciating Jane Jacobs, aside from her lucid prose, is her understanding of the ordered disorder and controlled chaos of a successfully working city, especially New York. Where Moses saw a future that was uniform, she saw a world order that was complex and intricate and involved all its inhabitants like “an intricate ballet.” To quote Jacobs, “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”