It was an embarrassing moment for Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti. What should have been a public demonstration of Swedish carmaker Volvo’s latest technology turned into an example of how self-driving cars depend on well-maintained infrastructure.

During the test drive at last year’s Los Angeles Auto Show, Volvo's North American CEO, Lex Kerssemakers, lost his Scandinavian cool after the prototype vehicle carrying the two men inched forward nervously in fits and spurts. The test vehicle’s onboard cameras were unable to collect enough visual data to signal the car so it could move forward smoothly.

“It can't find the lane markings!” Kerssemakers grumbled from the passenger side, according to Reuters. “You need to paint the bloody roads here!”

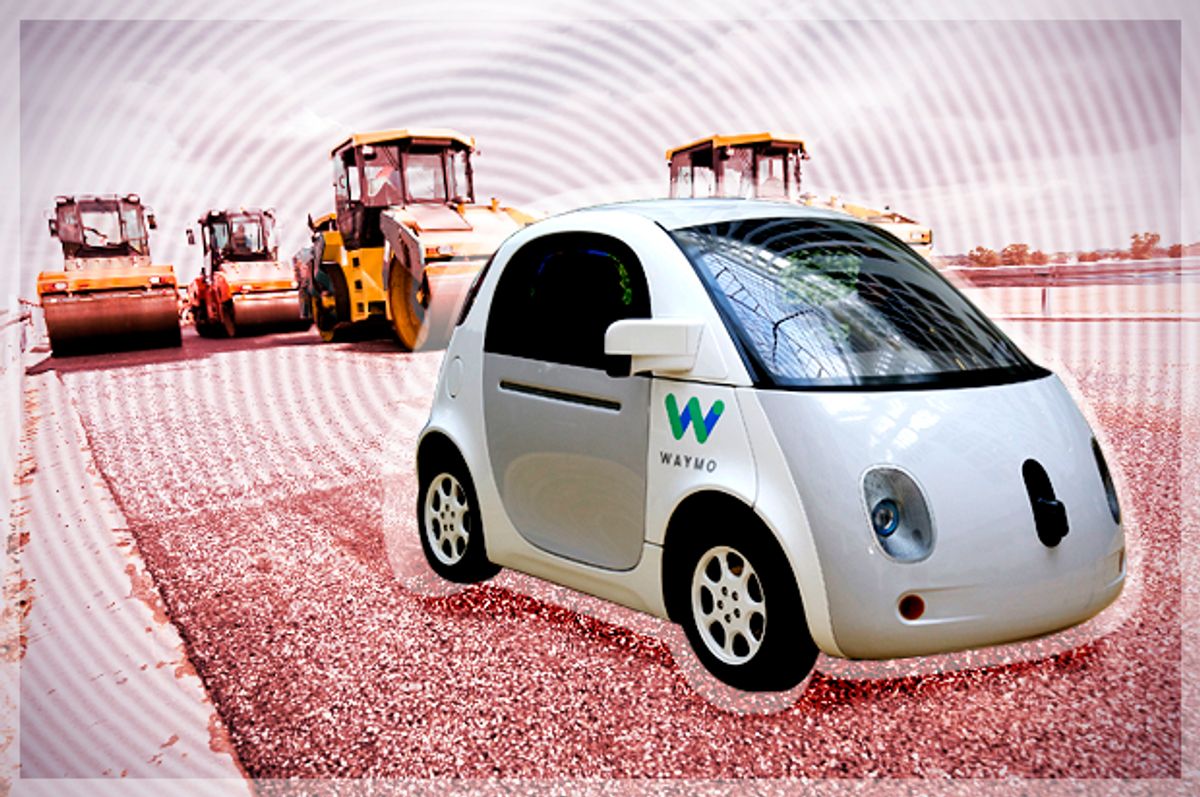

The incident underscored a major speed bump to the deployment of self-driving cars: the quality of the infrastructure upon which they depend.

“The maintenance levels on most of the roadway infrastructure are based on human vision, not machine vision,” Paul Carlson, a research engineer at Texas A&M University’s Transportation Institute, told Salon.

Indeed, as automakers start to deploy more autonomous features, including cars with intelligent, sensor-based cruise control, and in the future, self-driving passenger-carrying robots, one of the biggest challenges in rolling out the technology will be to ensure that the infrastructure is adequate and well maintained.

And automakers aren’t waiting around for federal, state and local governments to act.

Tesla became the first company to release in October 2014 an advanced form of sensor-based cruise control, called Autopilot, whereby the car automatically controls acceleration, lane keeping and lane changing but stops short of being completely hands free. Last week Cadillac followed suit by announcing its own version of this driver-assistance system, called Super Cruise, which will be available in its flagship Cadillac CT6 luxury sedan later this year. The luxury car division of General Motors has said this will be “the industry’s first true hands-free driving technology for the highway.”

Tesla’s and Cadillac’s systems work differently and have advantages and weaknesses. Super Cruise is based on a highly detailed map of the U.S. highway system but works only on highways with delineated on- and off-ramps. Tesla relies on a different system that depends on vehicles sharing map data that, for well-traveled routes, is improved over time. Companies including Google, Uber and Ford, are developing their own complex and varied versions of robotic-car technology.

Carlson compared the challenge of figuring out the infrastructure needs of autonomous cars to trying to hit a moving target. Automakers themselves are still figuring out the best ways to deploy the various types of autonomous driving features, so it’s difficult for officials to figure out what new standards will need at the federal level.

“If you listen to the automotive side, you hear different stories,” Carlson said. “You’ll hear some say, ‘We don’t need signs or signals or pavement markings.’ But you’ll also hear another side saying, ‘If you could put down more uniform, consistent types of infrastructure, we’ll be able to do this in an accelerated manner.’”

The U.S. has a national standard for the way roads are constructed and marked known as the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices. This rule book is the reason why important features like double yellow lines or red hexagonal stop signs don’t vary from state to state. But now authorities must figure out what changes are needed to accommodate partially and fully autonomous vehicles. Carlson, for example, is researching how to improve lane markers so that cameras can more easily detect them under certain daytime driving conditions.

The Department of Transportation itself is considering many new changes to accommodate the new driving technologies, including a fresh process of classifying road-readiness levels. This would help in labeling which roads could safely accommodate what types of autonomous vehicles. For example, a gravel road with no road markings would receive the lowest rating while a shiny new highway would obtain the highest marks. This is just one of many ideas under consideration to promote autonomous-vehicle-ready road infrastructure, Carlson said.

Last year the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration released its first policy guide addressing how to tackle the challenges raised by autonomous vehicles, so the process of establishing new rules has only just begun.

Nicole DuPuis, a transportation planning expert with the National League of Cities who is focused on how autonomous cars will be deployed in urban areas, said the infrastructure needs will depend on how the vehicles are used.

If, for example, future self-driving cars simply replace existing ones, and people continue to own one or more vehicles as they do today, then the infrastructure will have to handle increased congestion as cars drive themselves without passengers.

“However, if we deploy autonomous vehicles in fleets that utilize shared ride and ride-hailing models, we will have very different needs in terms of how we accommodate" autonomous vehicles, DuPuis told Salon by email.

In addition, DuPuis said, “There is definitely a need for coordination, both among city departments, and at the federal, state and local levels to ensure that new policy and priorities are cohesive.”

On Wednesday the National League of Cities released a series of recommendations for cities and states on how to best address infrastructure needs as the number of autonomous vehicles is expected to rise over the next decade. The report advised local governments to begin planning immediately, bringing together various interests, including infrastructure procurement departments, information technology experts and law enforcement officials.

“Municipal leaders should consider their short and long-term infrastructure needs, and ensure that any new investments better position their cities to support and integrate autonomous vehicle technology,” the report said.

Shares