I drove down to Charlottesville for a family meeting a couple of weeks ago. Ordinarily it’s a fairly easy drive, about eight hours door to door from out here on the East End of Long Island to the grassy horse country of Albemarle County, Virginia. If you leave early enough, you can skirt the traffic in New York City by taking the Belt Parkway to the Verrazano Bridge over to Staten Island, shoot across over to New Jersey on 278, pick up 95, and you’re on your way. But this was the Friday when the whole Eastern Seaboard was hit by pounding, relentless downpour that produced flooding and road closures near the coast. My little Kia hatchback held its own all the way to New Jersey. I had passed through the toll booths, and it was coming down really hard as I began the turn onto the turnpike entrance doing maybe 25 or 30. I was trying to make out the “north-south” signs up ahead when suddenly the back end of the car let go and came around hard to the right. I jerked the wheel into the slide, rode it almost to a retaining wall, and then the rear end swung around 180 degrees to the left; I spun the wheel to opposite lock and checked that slide, finally getting the car straight just as I hit the entrance ramp. That was when I noticed the entire road was awash in standing water. I must have hydroplaned, I thought as I loosened my grip on the wheel and took a deep breath. Out on the turnpike, the conditions were no better. Everyone was going about 50, trucks shooting up massive rooster tails, headlights on, wipers crazily working at the rain but just smearing it around.

The rest of the trip was more of the same — trucks going by in total white-out water sprays, everyone doing their best to keep on the road in weather that approached blizzard conditions with rain instead of snow. Because I had almost lost control of my car, I was super-aware that each of us had to be very careful out there, but we also had to trust that our fellow drivers were doing the same, forging an unspoken alliance so everyone got where they were going. The whole thing was kind of a miracle, really. It wasn’t us versus them. Out there in the rain it was just us. We drove through some of the worst weather I’d ever encountered, but I didn’t pass a single accident all the way to Charlottesville. We made it, we all did. Everyone on the New Jersey Turnpike that day drove with each other to get where we were going, and it worked.

I had just checked into my motel room when I realized that was the way the whole country used to work. No matter who you were, where you lived, what you did for a living, what your politics were, you were a part of a great unspoken national agreement that if you drove your life with respect for others, the whole damn thing would work, and we would get where we were going, no matter how bad the conditions were. Our parents made it through the Great Depression that way. As a country, we made it through the Second World War, we made it through Korea, we made it through civil rights and integration, we made it through the goddamned Vietnam War, we made it through riots and nasty recessions and technological changes that upset as many economic apple carts as they righted, we made it through long hair and burning bras and crime waves and one drug scourge after another, and we even made it through Thanksgiving dinners with each other without driving the country off the road. But while it may still be working out on the New Jersey Turnpike in the driving rain, it’s not working at home, at work, walking down the street looking at each other. It’s not working culturally, it’s not working politically, it’s just not working. We’ve given up on cooperating with each other so that everyone gets where they’re going, everyone benefits.

The evidence is all around us. Whole swaths of the country have been written off. Drugs like meth and oxycodone are leveling towns and villages like pharmaceutical smart bombs. Companies that used to consider themselves part of the communities where they built factories and paid taxes and contributed to the orchestra and the library and museum are now run out of PO boxes in the Caymans and Panama and couldn’t give a shit what happens to the people they lay off in pursuit of another point of profit, another billion in market value. Banks that used to take chances on people so they could build businesses and make things and provide services to the community are now so gigantic the very idea of community is a sick joke. People look at those who are different from themselves like they’re not “real Americans.” Politicians who we used to see in line at the grocery store are now tucked away behind private gates and key codes and squawk boxes and blacked-out SUV windows and can be seen only at occasional “town halls” patrolled by state cops. Presidents who used to take Marine One to Camp David for the weekend every once in a while now load half the White House on Air Force One and fly down to Mar-a-Lago so often they reserve airspace for them.

How did we get from there to here, from getting along and going along to looking at people like they don’t belong on the same sidewalk we’re both walking down? How did we become what people now refer to as two Americas, not one? I think we did it to ourselves, but I also believe we had some help. I got a terrifying glimpse of the future we’re struggling through way back in 1972. I was working for the Village Voice and the editor sent me out one freezing night in February to cover a political fundraiser for the Democratic Party, which was building a war chest to take on Richard Nixon in the fall. It was a cocktail party on the top floor of an apartment building on Central Park South. The fundraiser was given by a very wealthy woman who was prominent in the party, and her apartment took up the entire floor of the building. A half dozen windows overlooked the park and the sparkling city, and her living room was filled to capacity with tout liberal New York. Over there stood Wall Street titan Felix Rohatyn talking to Leonard Bernstein; nearby, labor attorney Ted Kheel had buttonholed Ted Kennedy; in the library, also overlooking the park, Norman Mailer was talking to former Mayor John Lindsay, who had switched parties and was contemplating a run for president as a Democrat.

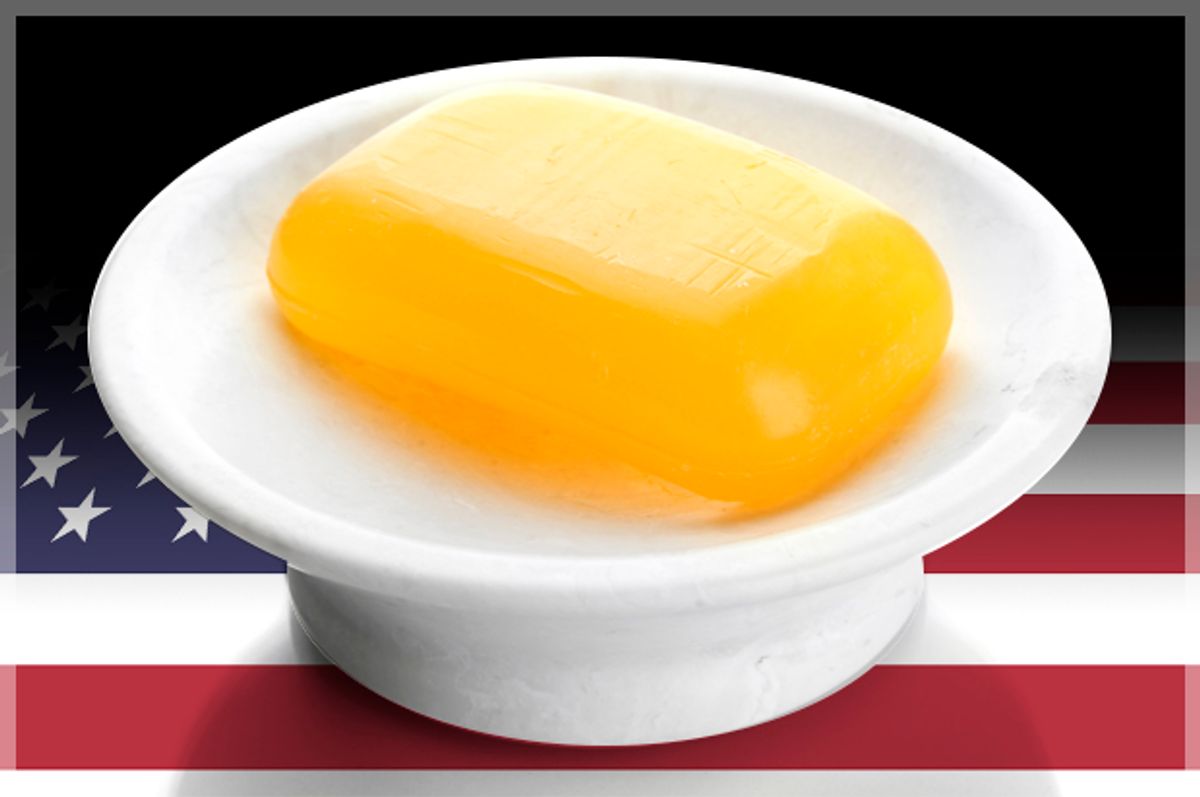

I wandered aimlessly around with my reporter’s notebook, not knowing what the hell I should be doing to “cover” such an august event, and I was about to leave when a middle-aged guy in a slightly rumpled suit stopped me. “You’re a reporter?” he asked. “Who do you work for?” I told him the Voice, which brought him up short for an instant, but then he recovered and introduced himself as an advertising man who hoped to work for the party on the upcoming campaign. He launched into an oration about how they’d been doing political advertising all wrong, but he had a new approach he knew from experience would work. “Do you remember the campaign for Dial soap?” he asked me. “I wrote it. ‘Aren’t you glad you use Dial? Don’t you wish everybody did?’” Dial wasn’t produced by Procter & Gamble or one of the other big soap companies. It was made by the meat packing company Armour & Company from tallow, a byproduct of the slaughterhouse. Dial worked its way into the market by being sold as an “anti-bacterial” deodorant soap. The ad man’s theory was to plant the idea in your mind that because of course you didn’t have B.O., you were already in the exclusive club of fellow B.O.-free Dial users, so the next time you went to the store, you’d automatically buy Dial. Well, it worked. A meat packing company beat the big soap companies, and Dial went to number one. This guy thought if it worked for soap it would work for political candidates, too. I don’t know if he ever got the job with the Democrats, but if he did, his subliminal sales theory didn’t work in politics, at least not in 1972, when Nixon won 49 of 50 states.

The Dial soap ad theory is alive and working well today, however, accounting for much of the balkanization of our politics over the last couple of decades. The idea that you, and people like you, are in a special club is essentially a tribal idea. We’re the ones who don’t have political B.O. Aren’t you glad you’re a Republican? Don’t you wish everybody was? Aren’t you glad you’re a liberal? Don’t you wish everybody was? Aren’t you glad you watch Fox News? Don’t you wish everybody did? Aren’t you glad you can recognize fake news? Don’t you wish everybody could? Aren’t you glad you’re white? Don’t you wish everybody was?

The people who are selling us this bullshit are doing it for the same reason Dial did it. To make money, billions and billions and billions of dollars. All you have to do is ask yourself that classic question: Who benefits? You don’t even have to hold up the highly divisive, highly profitable Fox News as an example. Take a look at who was to come out on top with the so-called “American Health Care Act.” Pick a pipeline, any pipeline. Pick any environmental regulation headed for the showers. Hell, pick the whole goddamned last election. We’ve gotten to a point where politics isn’t worth doing anymore unless it hauls in the billions. Screw those on the other side, and to hell with anyone who can’t keep up.

The ad man’s theory that worked selling soap has worked just as well to split us into tribal groups and reinforce ideas we already have about ourselves. You believe the same things, you watch the same shows, you listen to the same radio programs, you read the same news sources, you vote the same way, and everybody smells good doing it. It makes me wish we were all out there on the turnpike in the rain helping each other get where we’re going by simply doing what’s right.

Shares