Crime in 1856 was far more widespread than it had been years earlier. The increase in crime was always blamed on the ever- increasing population of the city, climbing to 629,810 by 1855. The number of residents approached a million by the very end of the 1860s, and police chiefs used the population in their reports to the mayor and Board of Aldermen, constantly whining that the huge number of people meant more crime. It was not the inept police; it was the population.

In 1855, Walt Whitman called New York “one of the most crime-haunted and dangerous cities in Christendom.” He added that by that time the criminal element in the city had been joined by new robbers and murderers who had moved to Gotham from other states, such as California after the gold rush there. They were, he said, “thieves, expelled, some of them, from distant San Francisco, vomited back among us to practice their criminal occupations.”

Crime was so prevalent, and the police were still so inept, that Whitman warned visitors to Gotham not to walk around alone at night and not to trust anybody. “Any affable stranger who makes friendly offers is very likely to attempt to swindle you as soon as he can get into your confidence. Mind your own business,” he wrote.

The Aurora editor told tourists, too, of “various kinds of scamps who do business upon the inexperience of strangers . . . sojourners robbed, swindled, and perhaps beaten.”

Whitman was one of many in the city who scoffed at newcomers and tourists. He told them all to stay inside their hotel and put their money in the hotel’s safe. Those who were robbed, especially those robbed in visits to prostitutes, gained no sympathy, just scorn, from newspaper people who told them that all they did when they reported robberies to the police or got into the newspapers as a victim was give advertising to the brothels where they were robbed.

How to stop all of the crime?

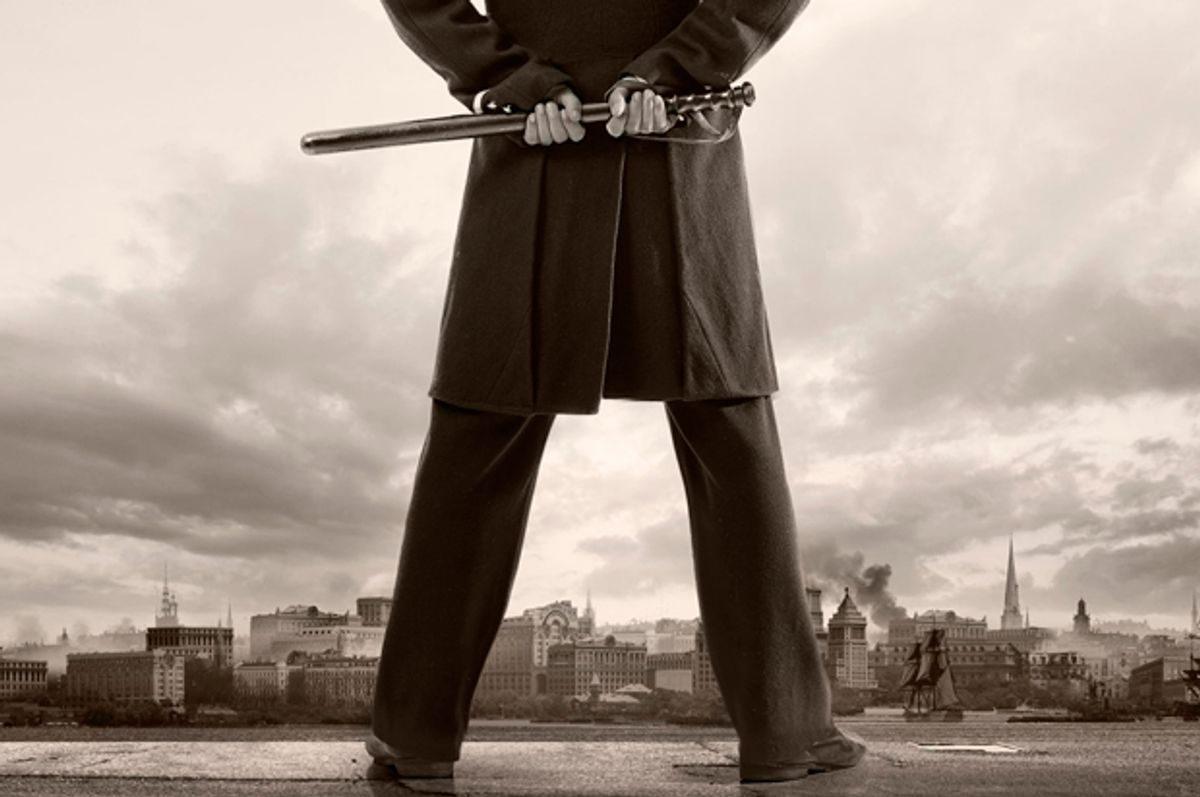

The cops on the first professional police force were told to be tough as soon as they were hired. The old constable had been not only ineffective but weak. Killers, robbers, and gangbangers had gotten away with murder for decades, and the public was sick and tired of it. The new officers were told to use as much force as they felt necessary to apprehend criminals and stem the ever-rising crime wave. A common practice was to crack criminals over the head, or across the back of the neck, with their thick, fourteen-inch-long wooden nightsticks, or billy clubs, regardless of the consequence. Police pushed, shoved, and kicked men down a street. Ears were pulled hard, throats were put in a vise hold, knee pressure was applied to the lower back, ankles were kicked, feet were stomped on. Usually, the nightstick blow to the head knocked men down, or unconscious, and sometimes victims later suffered brain damage.

Police argued that their job often made it impossible to keep the peace without violence. Patrolman Walling found himself the cop on the beat in a neighborhood in which most of the tenants on the east side of the street were English and those on the west side Irish. There were at least a dozen fights per night, and they were nearly impossible to break up. “After dusk the life of a policeman who patrolled the beat alone was not worth much, but by a severe course of discipline, the neighborhood was made safe,” he said, referring to cop beatings.

This was the “necessary force” needed to subdue a prisoner and was considered acceptable by police, city officials, and the public. The new police thought nothing of keeping control of a recently arrested prisoner by using their nightsticks. Some refined the technique by wrapping the stick in one or two handkerchiefs so that there would be no marks on it after a beating. Others only hit arrestees in soft places on the body so there would be no bumps or bruises to show violence. Many men were brought to the jail and then, hidden from the public, were beaten badly. Suspects in criminal investigations were often beaten up, kicked down stairs, and shoved against walls in the precinct house and forced to confess to crimes. This was soon dubbed “the third degree,” and it became an acceptable form of brutality. Force was often excessive. A Philadelphia woman was beaten to death by one policeman, and a bystander to an arrest who argued with the arresting officers was shot dead.

Police often advised victims of harassment to take matters into their own hands and beat up those bothering them. Captain Walling told one man to beat up the man who was annoying him in order to stop the man’s badgering. Walling assured the man that the police would not then arrest him for assault. He beat the man nearly to death; the man never bothered him again. Captain Walling? He said he knew nothing about it.

Sometimes brutality was carried out strictly by the book. A woman who was arrested in New York at her boardinghouse was forced to walk as quickly as possible, almost at a forced-march speed, through dreadful weather and amid streets of mud more than a few inches deep, lifting her ankles and knees up and down, for over a mile to the Tryon Row jail. She said that the walk through the miserable conditions wore her out and made her sick.

Officer Walling said that police supervisors offered few instructions on how to make arrests, disperse a crowd, or bring detainees to the precinct house. One problem police often had was when they confronted a group of rowdy men alone. Walling mastered the situation early with a persona of threatened force. He stood up to the group he was trying to disperse and told them to stop what they were doing or they would all be arrested. He pulled out his nightstick and held it in front of him, holding it tight, looking at each man with steely eyes and a hard-set jaw. There was then a quiet between them until the men realized that one or more of them was going to be hurt in a confrontation with the cop, even if they won the fight and escaped. “Well?” Walling would say. The men usually backed off.

Treating criminals brutally had another effect. Lawbreakers began to tell fellow felons they did not fear the punishment meted out by police courts, often lenient, as much as they feared the violence by the cop. A criminal could be permanently injured at the overly rough hands of the police officer, but not harmed at all by a judge. Fear of the brutal methods of the police began to intimidate criminals by the late 1840s.

The police also found that the immediate use of force quickly established their superiority in any confrontation and that the more criminals knew that, the fewer problems there would be. Police often plunged into a crowd of street toughs, hitting several over the head with their nightsticks. This measure often brought success and, overall, built up the image of all policemen as strict protectors of the law who got their way. Their captains not only looked the other way in cases of brutality but encouraged their officers to use whatever force they thought necessary to achieve their goals. A famous phrase was that the patrolmen needed to do whatever had to be done to uphold the law.

The public approved. Walling said that “by dint of a few hard licks” police did their work and that the public was so terrified of crime that they allowed the police a wide berth in making arrests. Force was a necessary evil.

There were many who were convinced that cops just had a mean streak and used their nightsticks, or any weapons they could find, in order to hurt people they suspected of lawbreaking. One was city political leader Robert Livingston, who testified at a state legislative hearing that “officers of justice, often uneducated or overbearing men, either do not know or designedly exceed the boundaries of their authority. The accused sometimes submits to illegal acts; in others, resists those to whom he ought to submit.”

Officers did not accept any verbal abuse, either, whether from those they arrested or bystanders. The cop had to maintain law, and to do that he had to be violent. People soon began smiling at cops as they passed them on the street, or tipping their hats. Men and women wished them a nice day or a good evening. Cop questions were always answered with a “yes, Officer ” or “yes, sir” somewhere in the conversation. Within a year, New Yorkers feared the new police and, intimidated, were congenial toward them. “There is no remedy for insulting language,” said one New York captain, “but personal chastisement.”

The police always defended their tactics, despite some public complaints against the increasing severity of the attacks by the men in blue. “A New York police Officer knows he has been sworn in to ‘keep the peace’ and he keeps it. There’s no ‘shilly shallying’ with him, and he doesn’t consider himself half patrolman and half Supreme Court judge,” scoffed Officer Walling. “He can and does arrest on suspicion. In times of turbulence or threatened rioting, he keeps people moving.”

The police Officer often kept them moving, and swiftly, with a few smacks to the back of the head with the billy club. Walling always used the billy club when he had to do so and urged all of his men to do the same.

Shares