On Tuesday, April 11 – the first day of the Jewish holiday of Passover – White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer asserted that Syrian President Bashar al-Asad was guilty of worse acts than Hitler when he used sarin gas on civilians. ![]()

Spicer said, “. . . someone as despicable as Hitler . . . didn’t even sink to using chemical weapons” on his people. The Nazis, as facts have shown, used Poison Zyclon B gas starting in 1939 on Germany’s mentally ill and physically disabled populations. Later, gas chambers became part of the Reich’s genocidal program in death camps.

The Anne Frank Center for Mutual Respect condemned Spicer’s comments and asserted that he was engaging in Holocaust denial – “the most offensive of fake news imaginable.”

“Fake news” is not a new phenomenon, nor is it always harmless. I am a Jewish studies scholar. My research in the history of anti-Semitism shows

that in 1913, “fake news” was used to feed into people’s fears and prejudices in America.

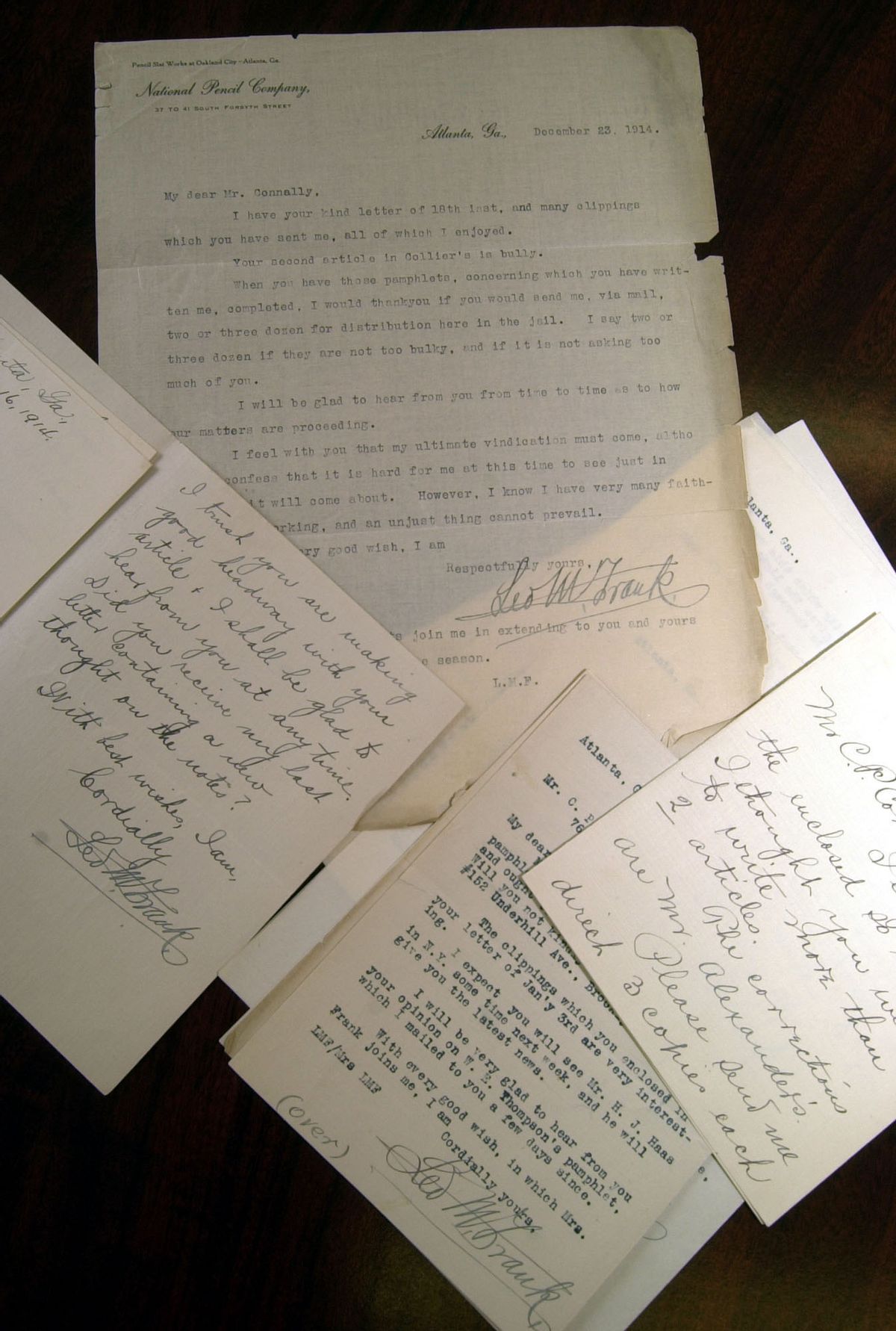

A particularly poignant story relates to the wrongful conviction of an innocent man named Leo Frank.

Who was Leo Frank?

Leo Frank was a young Jewish-American factory superintendent, who in 1913 was convicted of the rape and murder of a 13-year-old employee named Mary Phagan, whose body was found in the factory basement.

The Frank case was symbolic of many of the South’s fears at that time. Frank was a former New Yorker educated at Columbia University, and was for many southerners representative of the influx of northern businesspeople moving south to profit from the reorganization of a formerly agrarian society. That Frank was Jewish simply exacerbated these feelings. The evidence against Frank was circumstantial, but the jury found him guilty in less than four hours while crowds outside the courthouse shouted, “Hang the Jew.”

Frank was sentenced to death, and his initial appeals were denied. But on the recommendation of the presiding judge and additional new testimony, the governor of Georgia eventually commuted Frank’s sentence to life.

This did not placate the anger of the public, however. The governor attempted to protect Frank from mob violence by moving him to a state facility. But, on August 15, 1915, about 25 men launched an armed attack on the penitentiary. After cutting all the telephone wires leading into the facility, they seized the barracks where Frank was held and took him to Marietta, Georgia, where they hanged him near a crossroads.

Evidence suggests that the “fake news” that frequently appeared in at least one Atlanta area newspaper both before and during Frank’s trial helped keep readers’ emotions high and desirous of revenge for Fagan’s murder.

Approximately one month before Frank’s lynching, Chicago journalist and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Carl Sandburg wrote a scathing piece for the ad-free Chicago daily newspaper The Day Book entitled “How Hearst Treated the Leo Frank Case.” William Randolph Hearst was the owner of media company Hearst Communications and publisher of America’s largest newspaper chain.

The following opening passage from Sandburg’s piece expresses the intensity of American response to the Frank case:

“A whole lot of good people in Chicago wondered what all there was behind that Leo Frank case down in Atlanta. When a crowd of people go crazy and want to hang a man on little or no evidence . . . we don’t like it. This story is about things that happened in Atlanta. Yet it has a straight connection to Chicago. What happened in Atlanta can happen in Chicago.”

In this passage, Sandburg expressed that he as well as other Americans around the country – including those in the midwestern city of Chicago – were both baffled and frightened by the southern response to the death of Mary Phagan and the overwhelming outcry for Frank’s death as retribution, despite the absence of anything more than circumstantial evidence of his guilt.

Sandburg used evidence collected by another Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, A.B. McDonald, to “find out what made Atlanta crazy and how.” According to McDonald, the thirst for Frank’s conviction and hanging had been provoked, if not created, by Hearst’s daily newspaper, Atlanta Georgian.

McDonald traced no fewer than six stories about the Frank case appearing shortly after Frank’s arrest that were proven to be “fake news.” Two of those stories warranted official retractions (but that was done in small print, in the back pages of the paper), while another four were proven false in court.

Fake news and public emotions

Based on the phenomenal sales of the Atlanta Georgian during the Frank trial, McDonald and Sandburg both concluded that Hearst printed inflammatory and unsupported stories about Frank at least in part to sell more papers.

Both Foster Coates, a managing editor for Hearst, and Arthur Brisbane, editor of the Atlanta Georgian, attempted to persuade Hearst that Frank had not received a fair trial, and that it was the Atlanta Georgian’s

duty to calm public passions and demand justice for Frank. But Hearst flatly refused.

Sandburg concluded that Hearst “wanted Leo Frank choked dead by a rope . . . for a murder not proven in a fair trial.” Frank was murdered by a lynch mob a month later.

The Frank trial had lasting consequences. Mary Phagan’s murder and Frank’s subsequent lynching led to the B’nai B’rith Organization’s creation of the Anti-Defamation League, an organization founded to “stop the defamation of the Jewish people, and to secure justice and fair treatment to all . . .” This was especially meaningful because Frank was himself the president of B'nai B'rith’s Atlanta chapter before his arrest in 1913.

A dark outcome of the Frank case was the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan in 1917. The group’s revival is directly attributed to the Frank trial, which also inspired them to target Jews as well as black Americans with violence, hatred and bigotry.

Why this matters

Finally, in 1982, Frank was cleared of all charges after an 83-year-old man named Alonzo Mann gave a sworn statement to the newspaper The Tennessean claiming that Jim Conley, who worked in the factory as a janitor at the time of Phagan’s death, was in fact the real murderer.

Mann had even seen Conley lugging Phagan’s body into the factory basement, but was threatened by Conley into silence. Mann passed both a lie detector test and a psychological stress evaluation.

Leo Frank’s plight is a reminder of the toxicity of fake news.

Ingrid Anderson, Lecturer, Arts & Sciences Writing Program, Boston University

Shares