Less than two years after world leaders signed off on a historic United Nations climate treaty in Paris in late 2015, and following three years of record-setting heat worldwide, climate policies are advancing in developing countries but stalling or regressing in richer ones.

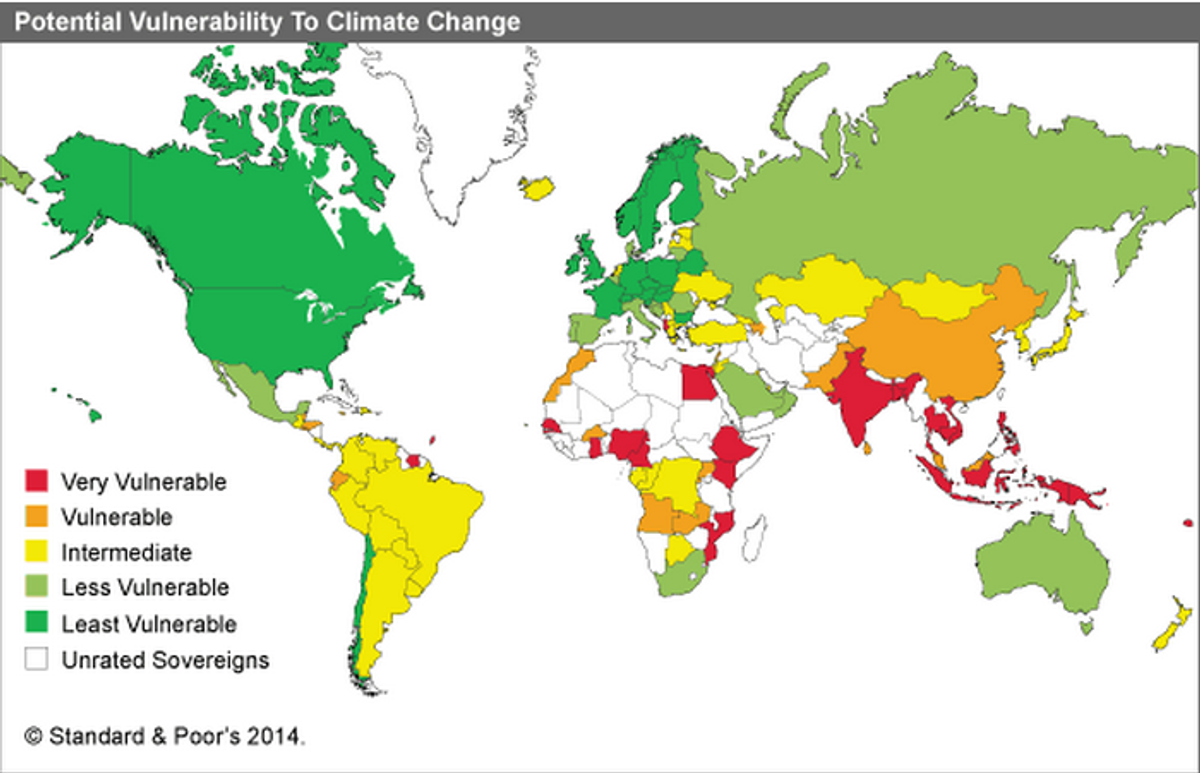

In the Western hemisphere, where centuries of polluting fossil fuel use have created comfortable lifestyles, the fight against warming has faltered largely due to the rise of far-right political groups and nationalist movements. As numerous rich countries have foundered, India and China have emerged as global leaders in tackling global warming.

Nowhere is backtracking more apparent than in the U.S., where President Trump is moving swiftly to dismantle environmental protections and reverse President Obama’s push for domestic and global solutions to global warming.

The U.S. isn’t alone in its regression. European lawmakers are balking at far-reaching measures to tackle climate change. Australian climate policy is in tatters. International efforts to slow deforestation in tropical countries are failing.

While global emissions of heat-trapping pollution appear to be stabilizing, they have not shown any signs of decreasing, which would be necessary to slow climate change. Rising temperatures are worsening floods, storms and wildfires around the world.

“Right now, when you sum the actions of all countries, even under the Paris agreement, it’s insufficient to mitigate dangerous, human-caused climate change,” said Matto Mildenberger, a political scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“Different countries move forward on climate issues with their own rhythm in response to domestic political factors,” Mildenberger said. “It’s naive to think that pro-climate forces will be in power across the world at the same time.”

Here’s a trip around the world, assessing how pro-climate and anti-climate forces are faring in key nations and regions and showing how recent developments are affecting the languishing fight against global warming.

United States

Dire. Trump moving to end climate regulations, research and spending.

No country has turned as sharply as the U.S. Since President Trump’s inauguration, America has gone from being a champion of global climate action to aggressively pushing to end environmental regulations and throatily advocating for fossil fuels. Scott Pruitt, who had been one of the nation’s most fierce opponents of federal environmental regulations, now leads the EPA, the very agency charged with overseeing federal environmental rules.

Trump has moved to eliminate any spending on global climate programs and to roll back any regulations that hamper the fossil fuel sector, which is the main source of greenhouse gas pollution. Many uncertainties over the future of U.S. climate policy remain, including its potential role in United Nations climate talks, and whether supporters of climate action can slow the reversal of national policies.

“The momentum that came out of Paris is still there,” said Harvard economics professor Robert Stavins. “But it has to be admitted that because of the election of Mr. Trump in the U.S., the overall global pace of action is now, and likely will be for the next few years, less than it otherwise would have been.”

Democratic-run states, of which there are just a dozen or so, and environmental groups are fighting Trump’s deregulation drive in public campaigns and in the courts. Trump’s Republican Party has slim majorities in Congress, and some Republican lawmakers have begun voicing support for climate action, making it unlikely that the Clean Air Act will be amended to ease the legal requirement that the federal government must regulate greenhouse gases.

Despite most Americans being supportive of climate action, recent Quinnipiac University polling showed half of Republican voters think Trump should remove climate regulations. It also showed that half of Republican voters think it’s a good idea for Trump to significantly fund research on the environment and climate change.

Canada

Concerning. Canada is moving to nationwide carbon pricing but is sending mixed messages on tar sands mining.

Canada flipped in late 2015 from refusing to act meaningfully to slow global warming under conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper to becoming an advocate for climate action after liberal Justin Trudeau’s party won the national election. But the prime minister has been sending deeply mixed messages about the future of the country’s heavily polluting tar sands oil industry.

Trudeau has moved to expand programs run by provinces that charge fees on climate pollution into a nationwide system. He has also said that Canada’s highly polluting practice of mining tar sands oil needs to be phased out. Then again, last month Trudeau said during a speech at an energy industry event that tar sands resources “will be developed. Our job is to ensure that this is done responsibly, safely, and sustainably.”

Trudeau released a federal budget last month that includes billions of dollars in spending on clean energy and climate programs, which Mike Wilson, executive director of the Canadian green economy think tank Smart Prosperity Institute, described as “a really positive development.”

“For Canada to significantly reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and be economically competitive in a low carbon global economy, we need both a price on carbon and targeted investments and policy directed at stimulating clean innovation,” Wilson said.

European Union

Concerning. Key votes loom as opposition and antipathy toward climate action grows.

The European Union was the first wealthy region in the world to take global warming seriously, but it has recently been floundering in its commitment to climate action, distracted by refugee and other crises and rattled by a surge in far-right parties within some of its member states.

Crucial votes by European lawmakers are planned this year, which will shape its plan for fighting climate action from 2020 to 2030. They have already committed to reducing greenhouse gas pollution by 40 percent by 2030, compared with 1990 levels, which is similar but less aggressive to a commitment made by California, one of the world’s leaders in fighting warming.

“I expect that the EU will stick to its objective to reduce emissions in 2030 by 40 percent, but will not go beyond this,” said Louise van Schaik, chief of the sustainability center at the Netherlands Institute of International Relations. “The opposition by Poland, Hungary and others is quite strong at the moment.”

Australia

Dire. After dumping its carbon tax, Australia may subsidize a large coal mine.

Australia’s commitment to slowing global warming has fluctuated violently in recent years, and it’s currently near rock bottom among developed countries. With little federal leadership, states have been stepping up to introduce their own climate policies.

One of the first major actions by the country’s conservative party after it won power in 2013 was to dump a carbon tax, which had been helping to slow warming. Since then, the ruling conservative party has replaced hard-right prime minister Tony Abbott with the more moderate Malcolm Turnbull.

The change in leader did little to bolster climate policy. Turnbull has been pushing for federal subsidies for a coal mine near the Great Barrier Reef, which is a major tourist draw and a breeding grounds for commercial fisheries that’s being destroyed by climate change — of which coal power is a major cause.

“There seems no political prospect under the present government for systematic climate policy instruments,” Australian National University professor Frank Jotzo, director of the Centre for Climate Economics and Policy, said. “At the right wing of the conservative government, there are those who would like to see a U.S.-style approach.”

Russia

Dire. After declaring climate change a crisis, President Vladimir V. Putin resumes his climate denialism.

Russia is one of the world’s biggest climate polluters, and it continues to rely on fossil fuel sales to Europe and other countries to underpin its economy. It appears to be preparing to ratify the Paris climate agreement, but that means little — Russia’s pledge under the agreement would not require it to take any meaningful steps to slow warming.

In 2015, Putin reversed his long practice of mocking and denying climate science, declaring that climate change “has become one of the gravest challenges humanity is facing.” After Trump won power in the U.S., however, Putin changed his tone again, saying climate change doubters “may not be at all silly” and that warming could boost Russia’s economy.

Vladimir Chuprov of Greenpeace Russia suspects Putin’s recent remarks were a “signal” to Trump, indicating that “we are the same” on climate and fossil fuel policies.

India

Positive. State and local governments boosting efforts to deploy clean energy.

India has developed one of the world’s most aggressive plans for installing solar panels, part of an effort by the large but low-income nation to provide electricity to the hundreds of millions of residents who currently lack regular access to it.

India’s ambitious clean power plans rely heavily on finance and aid from developed countries and experts expect they will be jeopardized by shifts in the U.S. and potentially elsewhere away from providing international assistance.

More recently, state governments in India have begun working aggressively to produce clean power and to help their residents adapt to the impacts of climate change. “This is the right approach, as impacts are understood better at local level,” said Harjeet Singh, a New Delhi-based climate policy lead for global nonprofit ActionAid.

“State governments as well as several local authorities are currently developing or implementing their plans,” Singh said. “A large part of money to carry the actions out will come from the national and sub-national governments, but international finance is also needed to boost these efforts.”

China

Positive. China views climate action as an economic opportunity.

China releases more heat-trapping carbon dioxide every year than any other country — a consequence of its large size and its role as a global manufacturing hub. Factories shifted away from the U.S. and other developed countries to China in recent decades to take advantage of its lax environmental laws and low wages.

China’s leaders have been toiling in recent years to reverse the policies that allowed wanton pollution of the water and the air, including greenhouse gas pollution. That shift has amplified recently as China has come to view clean technology as a major potential driver of its economy.

China aims to create 13 million clean energy jobs by 2020. In 2015 it overtook the U.S. as the largest market for electric vehicles. The country is delivering on its Paris climate goals far more quickly than it had anticipated, prompting some onlookers to speculate that it may boost its pledge during the years ahead.

“China is seeing climate change as an opportunity,” said Ranping Song, an expert on climate policies in developing countries with the nonprofit World Resources Institute. “China would be in a good position to boost its climate pledge, if the economic transition goes as planned.”

Amazon

Concerning. Deforestation accelerated in 2015 and 2016 following a decade of gains.

After a decade of success by Brazil in slowing deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, largely by preventing the conversion of forest into agricultural land for beef and soy, the country reported spikes in forest loss in 2015 and again 2016.

Amazon deforestation increased by about a quarter in 2015 compared with 2014, and them jumped by more than that amount in 2016.

Rachael Petersen of the World Resources Institute described the recent rise in Amazonian deforestation as “disturbing,” possibly caused by lax law enforcement of illegal logging and other factors. But she said it’s too soon to know if it was the start of a long-term trend or just a fluke. “The long-term trend is that it’s still downward.”

In nearby Paraguay, which shares a national border with Brazil and is home to a dryer type of tropical forest that’s not considered a part of the Amazon, Peterson described recent deforestation as “apocalyptic.”

Southeast Asia

Dire. The global hunger for palm oil is causing rampant deforestation in Indonesia.

Natural forests continue to be burned and cleared at astonishing rates to grow palms that produce palm oil in Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries. Land is also being cleared for timber throughout the region and to produce rubber in countries that include Cambodia.

This is despite a pledge by Indonesia to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by nearly a third by 2030. The country is one of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas polluters, largely because of deforestation. It’s also despite efforts by Unilever, Nestle, Mars and other global corporations to remove palm oil produced through deforestation from their supply chains.

Congo Basin

Dire. Deforestation is accelerating in Africa’s biggest tropical rainforest.

Deforestation has long been a major problem in the swampy Congo Basin in Africa, which traverses a number of poor countries and is home to one of the world’s greatest expanses of carbon-storing tropical forest. Timber is being harvested and trees are being cleared for mines, plantations and grazing.

The problem has recently been getting much worse, with “vast” new logging hotspots identified in an analysis of satellite images published in February in the journal Environmental Research Letters. Researchers found that the rate of deforestation more than doubled in the Democratic Republic of Congo 2011 and 2014.

“There are billions of tons of carbon locked up in those forests,” said Simon Counsell, executive director of the nonprofit Rainforest Foundation UK. “The threats are escalating.”

Norway and other countries have been committing hundreds of millions of dollars to help slow deforestation in the Congo, although the work has been criticized by Counsell’s group and other nonprofits for allowing and promoting commercial logging — something the international financiers regard as potentially sustainable.

Shares