Newfound confidence and feelings of safety. Concern about bullying. Changes in education. A worrying rise in legal questions about domestic violence and immigration. President Trump’s first 100 days in office have meant a variety of things to children, families and the people who care about them across the country.

Common Sense News spoke to children, parents, grandparents, teachers, lawyers and child advocates across the country to better understand what President Trump’s first months in office have meant to them. The conversations paint a complicated picture of a country trying to understand the Trump presidency.

‘After Trump, I got my voice.’

At 6-feet-3 inches, Reece Sherrill is tall for a 14-year-old. He’s on his Indiana middle school’s basketball team but has found himself, he says, sitting on the bench more than he would like. He contemplated transferring schools and finding a new coach until he watched Trump on the national stage.

“I liked his personality, he really gets to the point with stuff,” Reece said of Trump. So Reece, whose parents are lifelong Republicans, asked himself what Trump would do in his situation. He decided to talk with his coach.

“I was just like, ‘Is there anyway I could get my minutes, I’ve been playing my butt off,” Reece said. To his surprise, Reece’s coach responded well and he ended up playing more.

The moment was a turning point for Reece, who found that by emulating some of Trump’s candor, he found a new of way interacting with the world.

“I wouldn’t have said that before,” Reece said. “I feel like I would have just held back and kept everything in. I would have gotten sad or mad.”

“After Trump, I got my voice a little bit,” he added. “I say what I mean.”

A teacher tunes in, soothes fears

The day after the election, Sarah La Due, a 7th grade English teacher in El Cerrito, Calif., felt like she had let her diverse classroom of students down. “I felt like as adult we had betrayed for them the world we told them they were living in,” she said.

But since then, the teacher has doubled-down on her efforts to create an inclusive, sympathetic and informed classroom. Her school, Korematsu Middle, was recently named one of the most diverse in the San Francisco Bay Area.

La Due has made a point of never asking her students about their immigration status, although she knows the issue concerns any of her students. A fellow teacher learned a student’s father had been deported the morning before she came to school.

“I am more in tune to listening to their conversations, especially about deportation or immigrants,” La Due said. “A lot of times they make jokes about it. They use humor to cover up anxiety or fear.”

In response, La Due and her colleagues have been handing out cards from the ACLU that give advice in English and Spanish on how to speak with immigration agents.

La Due has also focused on current events, with special units on spotting fake news and bias.

“We did a lesson on pizza gate,” she said, referencing a popular conspiracy theory involving Hillary’s Clinton’s campaign and a pizza restaurant. “We’ve analyzed MSNBC news clips and Fox News clips and talked about how we saw bias.”

A deeper understanding of religion and identity

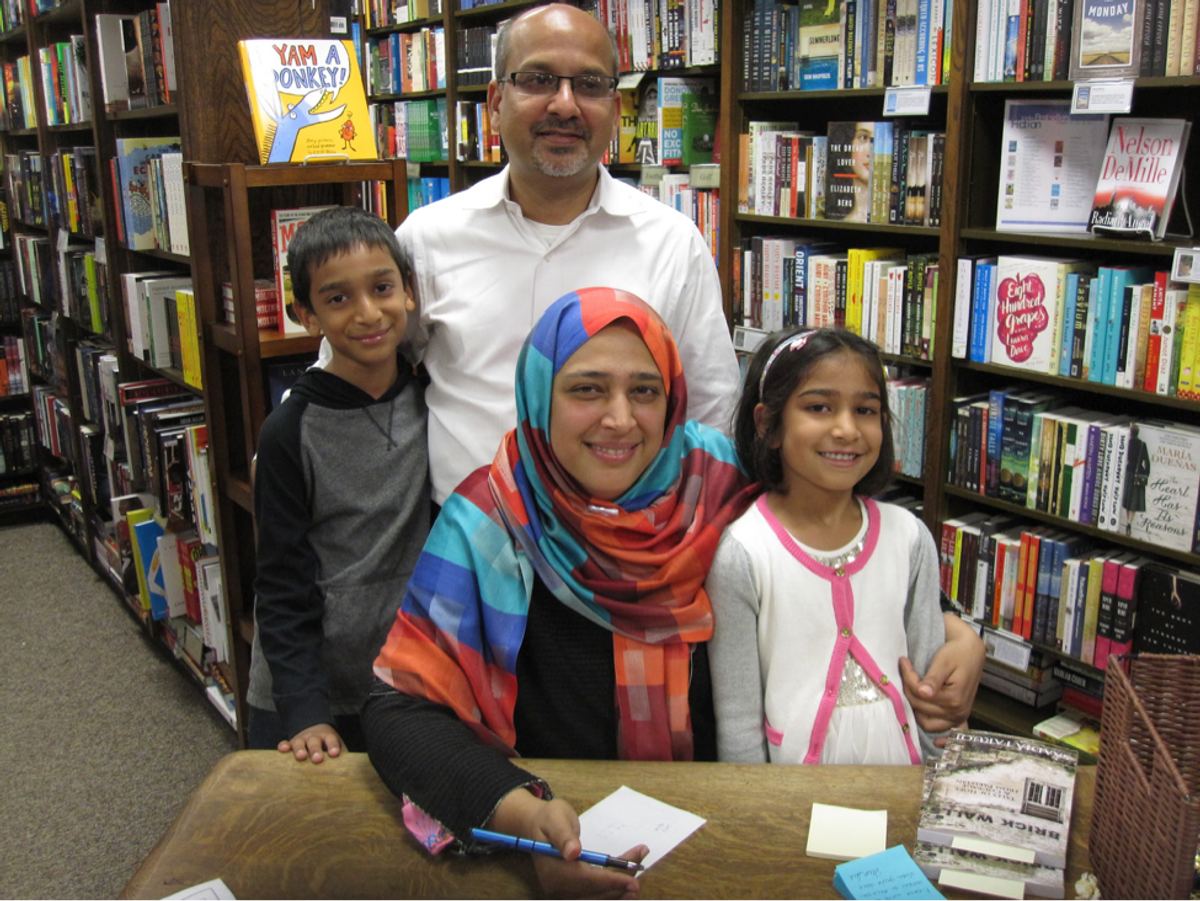

In Houston, Trump’s presidency has been unsettling for Saadia Faruqi, her husband and two children. The Muslim family has long felt welcome in Houston, which has one of the largest Pakistani populations in the country. But increasingly there have been flashes of hostility, especially at school with her 10-year-old son, Mubashir.

“Somebody said to my son, ‘You’re going to be kicked out,’” she said. “He very calmly turned around to the guy and said, ‘You’re so dumb. I am an American citizen, I won’t be kicked out.’”

Mubashir, who has been the victim of bullying even before Trump became President, has found new friendships with his classmates from Latin America in the last few months. “All of his friends are suddenly Hispanic,” Faruqi said. “I asked him why and he told me, ‘People hate Muslims and Mexicans, so I figured we have to stay together.”

Bullying has increased, even as “teachers don’t take it seriously,” Faruqi said. Other students “call my son a terrorist and I complain to the teachers and they laugh and say the kids don’t watch TV. I feel it is more blatant now. ”

Faruqi, a writer, said she has felt the animosity herself when she’s out at the supermarket or running errands.

“I feel like people are more able to say things that they maybe would not have said before,” she said.

But, Faruqi said, “I have also had people who have been acting more friendly than they would have before.”

And Mubashir has found a deeper appreciation for his religion.

“I have seen that he is more willing to speak out about Muslims about Islam,” Faruqi said. “The other day, a friend asked why he wasn’t eating pork and he said that’s what the Koran said. I was proud of him. At his age he doesn’t want to have a religious conversation. Every word is ‘whatever.’”

A threat to education

For Diane Ravitch, one of the leading advocates of traditional public education, President Trump’s first 100 days in office have been bleak.

“I think the most important thing he has done is appoint a secretary of education who is not a fan of public schools,” Ravitch said, referring to Betsy DeVos, a Michigan philanthropist who has no teaching experience and never attended public school. “I think she represents a very serious threat to public education.”

Ravitch, a former assistant secretary of education under President George H.W. Bush, said she worried Trump’s plan to let parents choose their child’s school could permanently undermine funding for public schools.

“I think that this could be very serious for the future of public education, pretty ominous.”

But not all the developments are distressing: DeVos’ confirmation hearing “became the fodder for late-night talk shows,” Ravitch said, generating new interest in public schools.

Membership in Ravitch’s Network for Public Education, a public school advocacy group, has surged from 22,000 members in September to 350,000 members today.

“People who never knew there was a secretary of education are now interested in the public education,” she said. “People became very aware because she is a lightning rod.”

In this Chicago home, a break from the news

Sonya Strenge, 36, had prepared what she would say to her 3-year-old daughter when Hillary Clinton won the election. But when she realized Trump would win, she turned off the news.

“I’ve never turned it back on,” she said. “My husband and I have kind of decided to shield her from this.”

Strenge and her husband occasionally watch topical comedians like Samantha Bee and Seth Meyers after their daughter Linnea goes to bed, but have otherwise avoided the news, which used to be a big part of their evening routine.

“Our media consumption has definitely changed,” she said. “We are very selective of what we want her to be consuming and very selective of what we watch in front of her.”

As Linnea gets older, Strenge thinks she’ll introduce more details about policy, activism and voting. But for now, Strenge wants her to focus on being a child.

“She’ll be in elementary school in two years, I am sure they are going to talk about the President,” Strenge said. “I don’t want to blind her and say, ‘We don’t have a President, honey.’”

New worry about police, violence

Like any grandma, Nadida Matin, 50, worries about her grandchildren. As a black, Muslim woman living in St. Louis she’s acutely aware of the threats she and her family can face from the government.

Her step-son, Abdul Kamal, was killed by police in New Jersey in 2013 and Trump’s support for police and lack of interest in reform makes her feel at risk. Kamal was unarmed, and was shot after he refused to take his hands out of his pockets, a New Jersey newspaper reported. Police called the shooting justified.

“Being a Muslim and having (Trump) say he is a law-and-order candidate, and having a step-son murdered by the police makes that even more concerning,” she said.

Matin is raising three of her grandchildren, ages 8, 10 and 11, and has made a point to talk to them about how to interact with the police.

“I tell them not to be fearful, to be engaged and know your own presence and strength; don’t be disrespectful,” she said. “We don’t allow them to go to the park unless we’re present. Stay in safe places. Don’t do things that would have people look at you as something other than your authentic self.”

But Matin, a lifelong activist, has also found that Trump’s presidency has revealed hard truths about race in America.

“Trump, he brought those thing to light that most people don’t want to talk about,” she said. “His being elected just made us have those conversations that we struggle with. He took away our ability to be ignorant to what’s going on. You no longer have the luxury to sit on the side lines.”

Feelings of safety in small-town Indiana

Rachel Kidd, 14, plays tennis and is on the cheerleading squad at her middle school in Bedford, Indiana, a town of 13,000 people. She wants to become a marine biologist or practice art.

But Kidd also worries about what she sees in the news: the threat of terrorism, ISIS and rising extremism. And so far she’s been very pleased with Trump’s aggressive approach to those issues.

"With us being in small town, I know we’re not directly involved in that stuff,” she said, referring to the threats of terrorism often felt in large cities like New York, Paris or London. “But what he’s doing makes us feel safer.”

“One thing that President Trump was really big on was protecting America and America First, and he stayed true for that; he has not let refugees in so far,” she said.

Kidd knows some people are threatened and hurt by Trump’s immigration policies, but she feels those stories are overplayed by the media.

“I hope that he continues to keep our country safe and stops many of the terrorist groups and the terrorist attacks,” she said.

A choice for parents when it comes to school?

For years, Neal McCluskey, an education scholar at the libertarian Cato Institute, has argued that parents should be able to take their child out of a failing public school and put them in a charter or private school of their choice. If schools compete, he argues, children win.

Donald Trump might make that a real thing.

Trump has said he supports school choice, and DeVos, his secretary of education, has long supported the policy. Neither have proposed detailed policy proposals.

But as much as he supports reforming the traditional public school system, McCluskey hopes Trump and DeVos will let states and local communities find their own way to the policy.

“I am pleased with the administration’s at least rhetorical move away from federal control of education, including Secretary DeVos stating multiple times in her confirmation hearing that education decisions are properly made at the state, local, or family level, not in Washington,” McCluskey said in an e-mail.

A strict reading of the Constitution gives the federal government little authority over local schools, he said.

“If the federal government tries to bribe or otherwise incentivize states to adopt choice programs we run a huge risk of the feds eventually regulating all private schools, rendering choice largely meaningless,” he said.

In Los Angeles, new interest in immigration rules

Jimena Vasquez is a family law attorney with the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles. In the last few months she’s seen a spike in the number of immigrant single mothers asking for help getting a passport for their citizen children without permission from the child’s father.

In many cases, Vasquez said, the men have been abusive and the mothers want to know how they can get a passport without the permission of their child’s father, which the State Department usually requires.

If an immigrant parent is deported, a passport will give their child an easy way to return to America when they grow older.

“I think among immigrants it is a valid concern of immigration enforcement,” Vasquez said. “If people are going to leave, they want to leave with their child. It is easier to get a passport here than it is there.”

The State Department is usually cooperative, Vasquez said, but the process can require unfamiliar and burdensome paperwork.

A renaissance of interest in local education

When Amanda Litman, a former Hillary Clinton campaign staffer, started Run for Something to encourage progressive millennials to run for local office, she hoped 100 people would sign up. Three months into Trump’s presidency, 9,000 have, and nearly a quarter have expressed interest in running for their local school board.

“I think folks are seeing that elections have consequences, especially for our kids,” she said.

That includes people like Shae Ashe, 27, who told NPR he decided to run for school board in his Pennsylvania town because “what happens on the local level is affecting your daily life."

Will Kane is a reporter for Common Sense News, an independent newsroom with Common Sense Media. For more stories like this, subscribe to the organization's weekly 'Kids in Context' newsletter.

Shares