Years ago, emergency room physician Dr. Basil Harris realized that a lot of the patients he was treating weren’t coming in with the kinds of severe trauma that ERs were designed for, such as car accident injuries or other immediate life-threatening conditions.

Instead, thanks to the lingering problems in the immensely overpriced United States health care system (where unlike every other industrialized capitalist democracy, health care is treated as a privilege, not a right), Harris routinely treated a lot of sick people who had nowhere else to go. One of the challenges, he found, was having enough information about these patients to rapidly diagnose their conditions.

So in 2012, Harris urged his siblings to found Philadelphia-based Final Frontier Medical Devices and help him design a device that could more easily enable people to regularly collect their vital signs and other health data and to store and compile the data in a way that could assist doctors in prescribing treatments.

A year into his project, Harris had an epiphany while reading an article about the Qualcomm Tricorder XPrize contest, which challenged innovators in the medical community to build a device similar to the medical tricorder, the fictional hand-held scanner used by the cantankerous Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy (originally played by DeForest Kelley) in the “Star Trek” franchise.

It was a no-brainer.

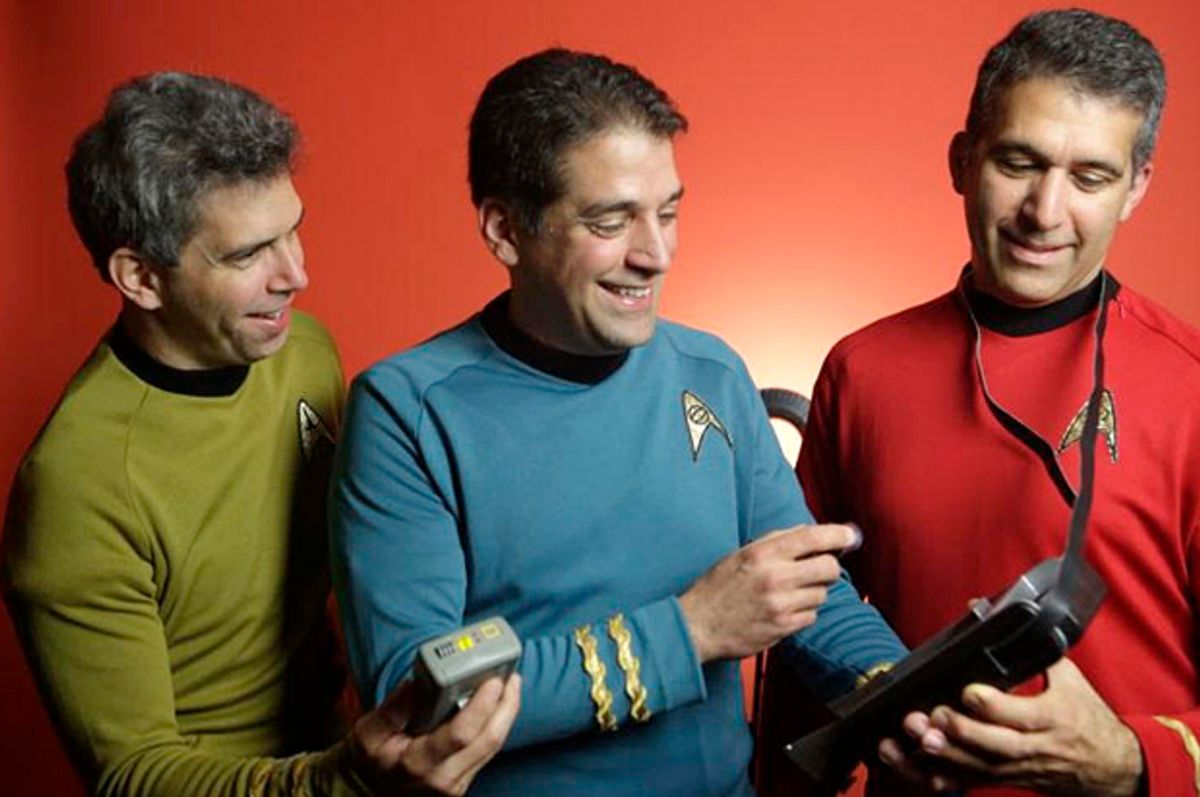

Harris, who comes from a self-described family of sci-fi geeks, entered the contest and his team continued to work nights and weekends on DxtER (pronounced Dexter), a tablet-based system that uses several biological sensors and analytic software that can track vital signs and uncover medical conditions — 34 in all, from diabetes and pulmonary diseases to tuberculosis and Hepatitis A.

The work on DxtER paid off this month when Harris and his brother George, a computer network engineer, led the seven-member team to victory in the international contest, beating runner up Dynamical Biomarkers Group., a Taiwan-based team led by Harvard Medical School professor Chung-Kang Peng.

The Pennsylvania-based team walked away with $2.6 million in prize money as well as extra cash to further develop DxtER for the marketplace with the help of University of California, San Diego’s Altman Clinical and Translational Research Institute.

DxtER (Credit XPrize)

The contest was orchestrated through the nonprofit XPrize Foundation, which organizes contests in various fields designed to spark leaps in innovation.

Dr. Harris spoke to Salon about his project and the future of diagnostics. This Q&A was lightly edited for clarity and length.

Tell me how you went from emergency medicine to inventing.

I’m still in emergency medicine, working full time as an ER doctor. That’s the same for my whole team. We’re all still working full time in our regular jobs. We got involved with the Qualcomm Tricorder XPrize kind of as a hobby, I would say. We’re really excited and thrilled that we got this far. It’s amazing that we took the prize; unexpected, I would say. [Laughs]

This has been a five-year journey so far. You started working on DxtER in 2012, right?

Yep, we got involved [with the competition] a little late in the game, in 2013. I caught news of the competition from an article in an online paper. I was instantly enthralled by it, this idea of building a tricorder.

Growing up, my family and friends were all “Star Trek” nuts and sci-fi geeks. And so the idea of trying to build the first tricorder, I mean, how awesome is that?

Obviously it’s not exactly same thing as Dr. McCoy’s medical tricorder, but what’s similar is that DxtER performs three functions: It receives information from the biological sensors and it automatically analyzes that data to provide a diagnosis.

Exactly. It is different than what is on the TV series. On the TV series Dr. McCoy would hold the tricorder, look at it and scan his patients. But then the information that it was gathering, he still had to interpret it; he still had to come up with the diagnoses. So the XPrize Foundation said: “Oh, well, that’s too easy. Let’s put McCoy into the machine.”

That’s the part that got me really excited, because [making diagnoses] is what I do every day. I’m in the ER. Patients come in from many locations; all types of patients, all types of ailments. It’s not all blood and guts and trauma. Most of the patients that come in to my department are just there for routine medical care, because they have nowhere else to go. I’m in Philadelphia. We have these huge towers of medicine here, technology that is incredible, but there are still so many barriers to access that we have whole communities that are cut off from accessing that great medical care. It’s a frustration of course on the patients’ side; it’s a frustration on the providers’ side. This is a tool that I think could help bridge this gap.

You’ve also said that the era of putting blind trust in the medical profession is over. Are we going to see a time when patients will use technology like this to self-diagnose and then go into the doctor’s office and say: ‘Doc, this is what I have, what treatment do I need?’

That is a dream for the future. There are many steps to get there. The Qualcomm Tricorder XPrize was a demonstration that showed fully automated systems that are cut off from outside input so that they needed to make all of the [diagnostic and prescription] decisions on their own. That’s a system that’s off on the horizon. Artificial intelligence and these learning machines that are trying to act like health care providers and make important decisions are going to have to earn our trust — as regular consumer and as physicians.

It seems like DxtER or something like it could improve over time as more data is available to it, much like how IBM’s Watson supercomputer is changing diagnostic medicine.

Big data analyses I’m sure will enlighten us in ways we don’t even know yet, but when I’m in the ER making a diagnosis I know what data I’m looking for. I want to have reliable data coming into a system. We have to be able to gather robust information. Vital signs are one part of it, but so is other objective information that’s trustworthy enough that we can say: “Yes, we’re going to make a medical decision based on this information gathered by the consumer in his or her own home.” That’s empowering.

People come into the ER with information they’ve gotten from the internet, from devices they have at home — strips of paper where they’ve jotted down their glucose reading or their blood pressure — and we use that information to help manage diseases like diabetes or congestive heart failure.

I dream of a time when someone comes into the ER with their “tricorder” — whether it’s this system or others that are being developed — and they say “my device at home tells me I have pneumonia; this is how I’ve been feeling and here’s my stream of vital signs from home, and the data I’ve collected. I want to know I can believe this information and go to the next step [in treatment].”

That’s where we’ll gain some efficiency in the system. People will have information they can rely on to make real decisions when they have limited access to care. In the middle of the night when you’re caring for a sick child or elderly parent and you’re trying to figure out what to do, a phone call to the primary doctor is great. But imagine if that doctor had access to a reliable stream of data during that phone call or that video chat, real vital signs coming through [via an internet-connected device], real lab data that could be used to come up with a decision and a plan. That’s where we’re headed with this.

The original challenge was to create a device that could diagnose 13 medical conditions, including common ones like diabetes and pulmonary disease. You nearly tripled that number, to 34. What were some of the additional conditions you decided to include and why?

There are some conditions that are pretty common. The way they designed the contest was to show a wide variety of conditions, including chronic diseases, things that span multiple body systems. To make it a truly useful device, we’re going to have to approach 100 or 200 conditions, because you want to rule other issues out. We added maintaining health for people with asthma. We also included ways to diagnose stroke, which is so critical. Unfortunately, I see so many times people wait too long to get stroke care. Getting stroke care fast is a big deal. Those are a couple of the health issues we decided to include.

Now that you’ve caught the attention of the XPrize Foundation, what’s next for DxtER?

We have a clinical trial underway at my institution, Lankenau Hospital in Philadelphia, and we’re moving forward with testing the individual sensors. These are the less glamorous tests where we have to gather the data, prove to the medical community, prove to the [U.S. Food and Drug Administration], and get the approvals so we can get this out there.

Shares