A few years ago, I taught Margaret Atwood’s novel "The Handmaid’s Tale" in a humanities lecture at a small Midwestern university. On the first day we were scheduled to discuss the text, I conspired with my co-faculty to enact a mock-banning of the book. It had landed on actual banned books lists before, put there by those averse to the dystopian themes of environmental wreckage, women forced to serve as baby incubators to the powerful and infertile, and too much government control. To illustrate, I would pretend such a ban was happening on our liberal arts campus.

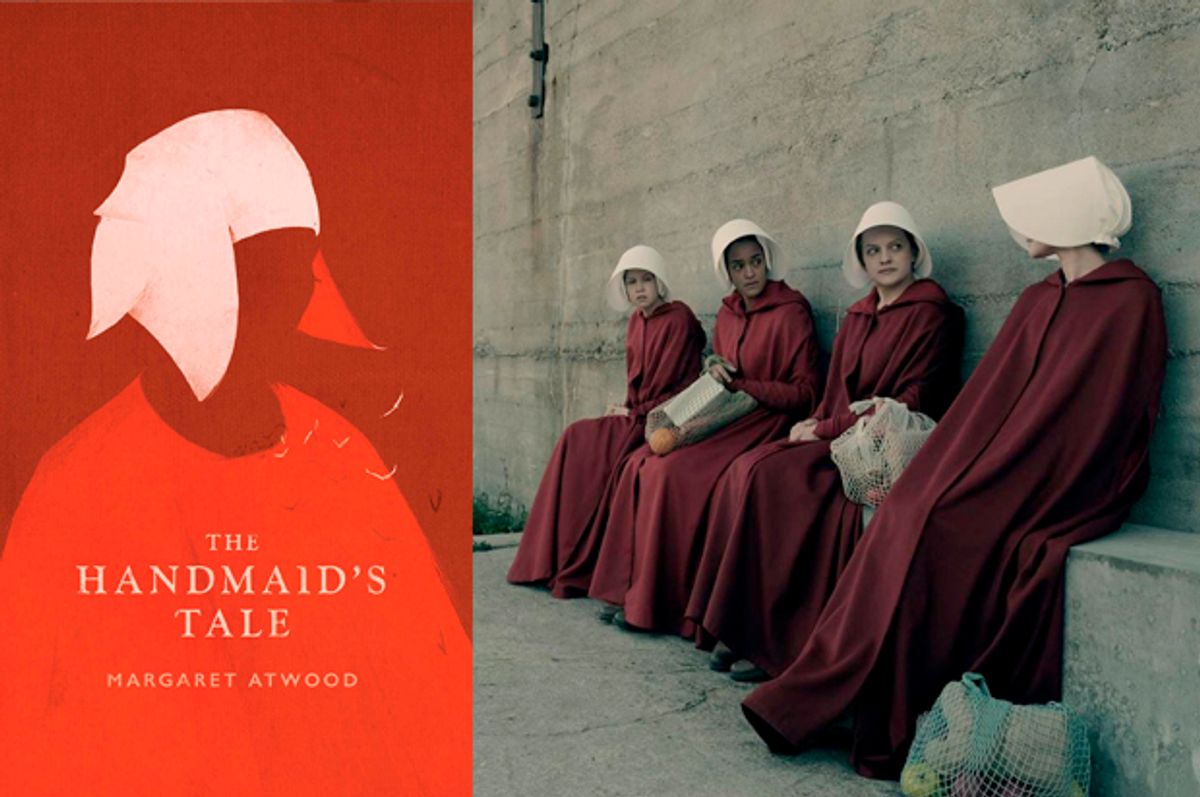

Enlisting a campus security guard to interrupt my lecture, I feigned shock, disgust and reluctant resignation at the made-up “order from the Provost” to confiscate every copy of the novel. Our edition bore a black-and-red cover, depicting two featureless handmaids passing each other in a shadowy corridor.

The students' reactions were intense and varied. Some appeared concerned for me, clutching their own copies of the book and looking from me to the security guard (whose holstered pistol sat on one hip) and back again. A few were skeptical and claimed ownership of their capital.

“But we paid for our own books!”

“I was going to sell it back!”

Others murmured and asked questions. And one young man in the back held his book in the air as if being relieved of a great burden, as if he were raising a white flag of surrender to the act of reading.

“Here you go,” he said, and I added it to my growing stack.

Back at the front of the lecture hall, I prepared to deliver our books to the guard.

“Hold on,” said one shrewd student whose papers for class revealed more than she volunteered in discussion. She was a complex thinker, an empathetic reader, and a veteran who had served in the Middle East.

“You’re messing with us,” she said. “No way this is real.”

I admitted the ruse and gave them a minute to settle down, and the security guard took a theatrical bow. Then I played a brief clip from the 1990 movie version of "The Handmaid’s Tale," and we moved on to discussing theocracies, America’s Puritan roots and anxiety and obsession over the female body. I showed them current popular magazines featuring pregnant, naked celebrities, hands and legs strategically placed; we compared the images to a picture of Venus of Willendorf, the Paleolithic fertility statue.

This was 2013, and so we scrolled through Margaret Atwood’s Twitter feed, where she interacted with fans, posted articles about reproductive rights and the environment, and occasionally retweeted strangers’ various causes upon request. "The Handmaid’s Tale" was relevant to readers then, but not with quite the same urgency as now: a new Hulu series based on the novel launched Wednesday, with a months-long buildup that matched this politically charged time.

[jwplayer file="http://media.salon.com/2017/04/efa14cc6bcd4e1b261b17c9e2eca8bc0.mp4" image="http://media.salon.com/2017/04/7dd78364a04c079e20d19821fa204fd0-1280x720.png"][/jwplayer]

Two weeks after Donald Trump's inauguration, 'The Handmaid’s Tale" was one of several dystopian novels — along with George Orwell’s "1984" — seeing a resurgence on bestseller lists. Following the Super Bowl’s commercial teasers for the show, the novel hit Number 1 on Amazon’s bestseller list. And after more than three decades in print, it also made the New York Times bestseller list.

Looking back to that class, our conversation felt very theoretical. We were supposing, imagining, thinking about issues of literacy and censorship. During the lecture, I asked the students, Why did some remain seated? Why did some protest? And what of our willing witness to censorship, the man in the back, who gratefully unloaded his text? I’d say it was for a laugh if his face hadn’t been so serious, almost grateful.

In the book, Offred is a handmaid to a Commander named Fred (forget her old name; now she is “of Fred”). Stripped of agency, dignity and identity, we live in her first-person narration. Her Commander is perhaps kinder than most; he allows contraband magazines and games of Scrabble. He allows words, language. During sex, described as “The Ceremony” and for reproductive purposes only, his wife reclines on the bed, Offred lays back on her stomach, wife grips Handmaid’s hands and the Commander proceeds. Offred switches to third person: “One detaches oneself. One describes.”

One reads such description and decides what one thinks. In humanities class, we talked about how freedom could be chipped away one piece at a time. I asked, What are you willing to give up? Your books, and then? What are you willing to fight for?

One student, a woman in her early fifties and back in school to finish her undergraduate degree, raised her hand. She had scars along her jaw that gave the appearance of a permanent smile. She frequently volunteered in class, always with that hint of a smile on her face. Even then, while her eyes were tearing up. “All I know is that you can never give up,” she said. “You have to keep trying. You have to keep going. Always.”

Initially this resonated with me on a surface level: Nontraditional students often overcome great obstacles to finish their degrees, and she was a dedicated worker who put in extra time to earn good grades. I wouldn’t understand the significance of her words until later, when she used Atwood’s book as a prompt to write about her scars. They were the result of surgery to repair the damage from a man’s abuse. He’d broken bones in her face.

Playing along and confiscating books, I acted in a made-up scenario. If someone really came for my course texts, I’d like to think that I would put up a fight. I’d like to think that I would make a fuss. When I asked those who were quiet why they had obeyed, one young woman spoke the same fear that lives in the back of most people’s brains, mine included: “A man with a gun told me to do something. So I did it.”

Anyone who has given a passing glance to the news and social media in the last six months — and most of us have dedicated countless hours of time and energy to staying current — knows these are trying, anxiety-filled times. Atwood’s fictional regime seems uncomfortably close. I’m scared, friends say, in person and online. I’m overwhelmed. What will happen to me? To us? To our country? Alongside news headlines updated hour by hour, we see articles promoting psychologists recommending we go offline, stop reading every article and practice self-care.

When the internet delivers an information onslaught, books offer a brain reboot. The resurgence of "The Handmaid’s Tale" may come partly from the fear and anxiety of our time, but it also shows that people want to read about censorship and literacy, not be censored and become illiterate. The novel has staying power, as does any story that tells us about ourselves and helps us empathize with others. Stories are like life manuals, and we read to be inspired, to heed warnings, to mobilize, to learn What Not to Do.

Reading books is a radical act when ideas are threatened and words are redefined. Attempts to control language are attempts to control thought. Orwell’s novel "1984" springs to mind, with its Newspeak and thought control. All languages serve as an agreed-upon code; those who know the code get the message. In Atwood’s novel, Offred needs help deciphering a Latin phrase she finds written in her room, likely carved there by the home’s previous handmaid. Nolite te bastardes carborundorum. Atwood’s fans tweet her pictures of their Latin-script tattoos, making permanent a language that in the novel is cryptic and hopeful, encoded and eventually decoded.

Nearly four years later, I have forgotten the name of my student who served in the military, but I remember her piercing blue eyes and sharp brain. Her sense of humor, and also fatigue. Once, she asked to speak to me in the hall: She had PTSD and couldn’t tolerate startling noises. Sometimes she might need to leave class during the music lectures.

She had asked me if the book banning was real. Once I’d revealed that it was a ploy, a way to demonstrate censorship, she watched me closely. She had served the United States overseas, defending the freedom to read books others might find contentious. Her smile was faint, worn.

“I knew it,” she said, nodding. “I knew it.”

She turned to the projection screen, to the picture of a tattooed arm bearing Nolite te bastardes carborundorum, the Latin phrase for “Don’t let the bastards grind you down.”

She bent over her notebook. I watched her inscribe the words.

Shares