On a Monday morning last October, Sascha DuBrul awoke later than usual, with two ringing ears. Less than twelve hours earlier, the 42-year-old DuBrul had been reliving his youth, stage diving into a packed crowd in Brooklyn’s Warsaw Ballroom. His old band, Choking Victim, had reunited for a rare performance. Their music, a relic of Manhattan’s early ’90s punk scene, has been discovered in the last few years by a new generation of teenage punks. And now, those teenagers were busy posting pictures from the show online.

DuBrul needed to run out the door to make it to the office, but he couldn’t resist a quick scroll through social media, where he maintains a modest-but-loyal following. He re-posted a photo that captured him, bass guitar in-hand, shouting into a microphone at the edge of the stage. He added his own caption: “No one at the office has any idea.” Then, he closed his laptop, and with fifteen minutes to spare, left his apartment and headed to work at Columbia University’s Medical Center.

DuBrul is part of a small team of clinicians who are bringing a specialized model of care for adolescent and young adult psychosis patients to the New York State Psychiatric Institute’s state-of-the-art facility on Columbia’s campus, a stone’s throw from the Hudson River. Their goal is to create a highly personal, supportive treatment program, wherein a collaborative group of mental health professionals — including physicians, psychiatrists and education or employment specialists, among others — establish close relationships with patients and help them create a clear plan to implement after they’ve been released. In announcing that New York’s Office of Mental Health would fund the program to the tune of about $7 million, legislators and public officials spoke of its promise. “Early intervention can save lives,” said Governor Andrew Cuomo, “and with this funding we’re going to be able to reach more young adults battling mental illness and put them on the path toward comprehensive treatment.” Many believe this type of innovative approach to mental healthcare can be a blueprint for hospitals and clinics across the country. This is why DuBrul was so proud to join the Psychiatric Institute last year, although, as he readily admits, he was an unlikely hire.

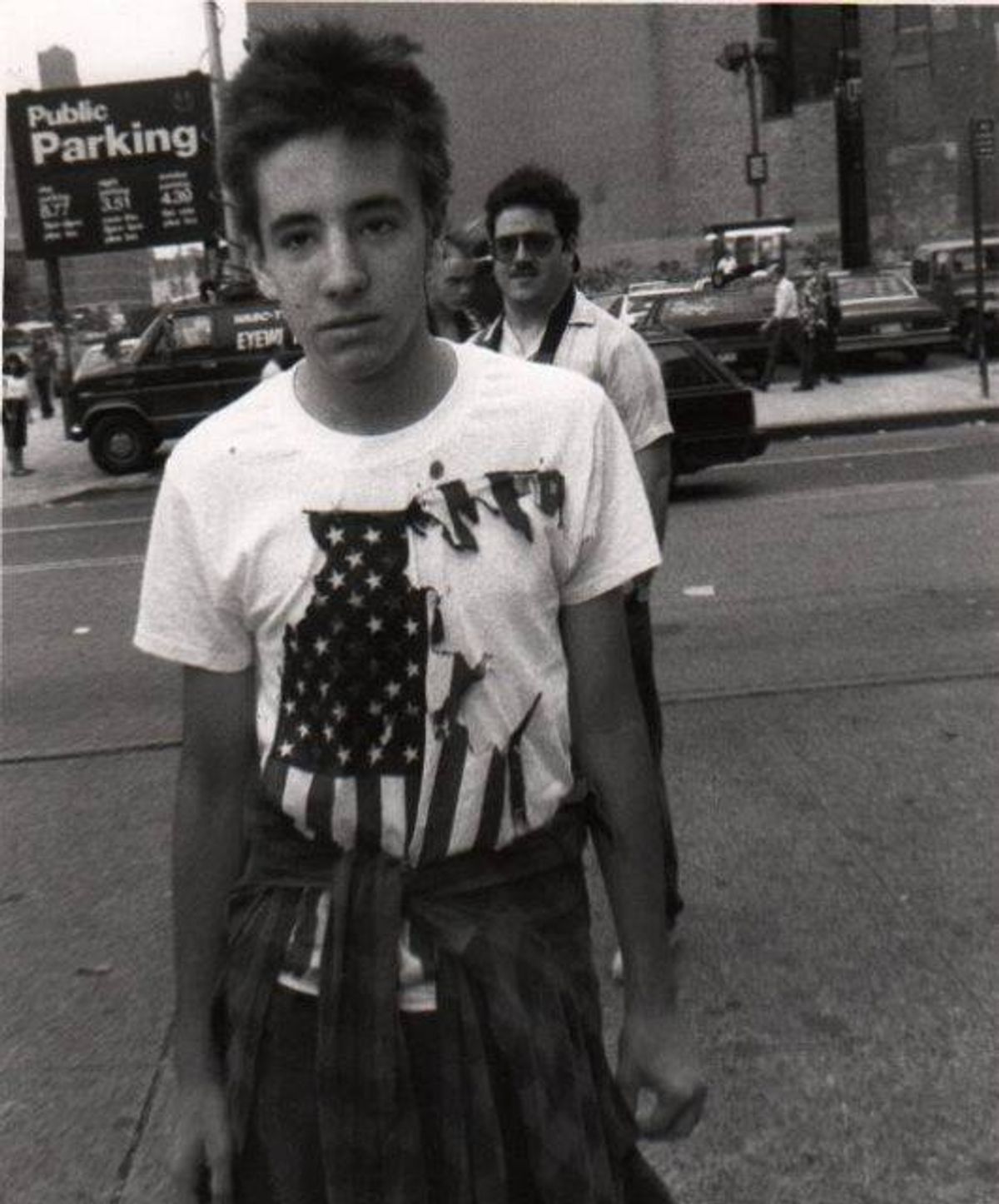

DuBrul did not spend his early twenties in medical school. “When I was 25, I didn’t think I was going to live to be thirty — and so, I lived in such a way that I wasn’t thinking that I was going to be around,” says DuBrul, who tends to speak with both his words and his hands, with the dramatic flair of a seasoned performer. His hair, short and cropped, is jet black, except for a small patch of gray on one of his sideburns, as if middle age surfaced and felt unwelcome. DuBrul spent his would-be college years crisscrossing Manhattan’s Lower East Side, living as a punk squatter in cooperative housing. He was 37 when he finally completed his bachelor’s degree.

But NYSPI did not bring DuBrul aboard for clinical expertise. Rather, they hired him because he has experienced the system from the inside, as a patient. He’s a peer specialist, and his job is to train other peer specialists who will work directly with these young folks who have just experienced their first episode of psychosis. “It’s called being a wounded healer,” he says.

* * *

When DuBrul was eighteen, living with his mother on Upper West Side, he became convinced that microscopic transmitters had been embedded under his skin, and that his every move was being broadcast on live television. He hadn’t slept for what felt like months when, late one evening, he began pacing his bedroom, sifting through old family photographs and digging up childhood toys. He built a shrine to his youth, and then snuck out of the apartment.

On foot, DuBrul hurtled downtown. At 23rd Street and Sixth Avenue, he descended the stairs to the subway station, hopped over the turnstile, and raced to the platform. Then he leaped down onto the tracks. “I just had this sense that there was nothing I could do wrong,” he remembers. It was “a very liberating feeling.”

With his arms extended in crucifix, DuBrul began walking the tracks as if they were two tightropes stretching toward another world — because this one, he was certain, was about to end. Am I just here alone, he thought, or am I being watched? And whoever is watching me, who’s watching them? Waiting passengers noticed him and began screaming. The police arrived, jumped down onto the tracks, and wrestled him to the ground. As one of the officers fastened handcuffs around his wrists, DuBrul asked, “Who watches the Watchmen?” He was in psychosis.

At the hospital, doctors sedated DuBrul with antipsychotic medication as well as Depakote — an anticonvulsant drug, often used to prevent epileptic seizures, which psychiatrists also prescribe as a mood stabilizer. They diagnosed him with manic-depression, a condition now known as Bipolar I — the more severe form of the disorder, characterized not just by mood swings, but also episodes of mania, or psychosis, which cause delusions, hallucinations, and disordered thinking. DuBrul spent the next four-and-a-half months in psychiatric care. The doctors told him that, going forward, his life was going to be a lot more “contained” than he might’ve imagined.

But by the time he was released, DuBrul was determined to prove them wrong. In order to do that, he left home and made his way to the Lower East Side. Among the punks, who proudly wore indignation on their sleeves, his hostility toward the psychiatric system was a badge of honor. The punk kids, many of whom had suffered similar fates in the psychiatric and foster care systems, lived in unabashed opposition to mainstream cultural norms and expectations. They occupied their slice of Manhattan in a shared spirit of defiance. For DuBrul, who’d just escaped hell, the Lower East Side became home.

He took sonic refuge in punk music’s frenetic instrumentation and in-your-face melodies. And as he began to experiment with writing his own songs, DuBrul found his voice in culturally subversive lyrics. His newfound confidence was unmistakable to those around him. Jennifer Bleyer, who remains one of DuBrul’s closest friends, remembers meeting him shortly after his hospitalization. “He was incredibly passionate and extroverted and just dynamic,” she says. “He had an incredible magnetism.”

Over the next six years, DuBrul was able to build a life in perfect opposition to one that could be described as contained. He and two of his closest friends formed Choking Victim. It wasn’t long before the band became a favorite among the punks, who crammed into basements and small clubs and shouted along to songs like “Fucked Reality” and “Apple Pie and Police State.”

“Thank punk rock,” DuBrul says, “for giving me . . . the space to just be myself, and not be afraid of my anger and madness.”

But after he turned 24, DuBrul found himself overcome by a wave of depression. Then, for the second time, psychosis struck with a sucker punch. It sent him staggering through the city streets, unable to follow simple directions or find his way from one corner to the next in the neighborhood he called home. His clothes dirty and torn, DuBrul ended up in fetal position on the kitchen floor of his mother’s apartment with his hands caked in dried blood from cuts that had become infected. He told her that he was going to end it. He was ready to commit suicide. She enlisted the help of family and friends and, together, they rushed DuBrul to the hospital.

* * *

After his second prolonged stay in psychiatric care, DuBrul was desperate for a clean break. He needed to get out of New York — far away from everything and everyone he knew. So, with the little money he’d saved, DuBrul moved to California, where a chance encounter would change everything.

It was there that he became friends with a journalist for The San Francisco Bay Guardian who asked DuBrul to write about his experience for the newspaper.

In his essay, “The Bipolar World,” DuBrul described the suffocating isolation he’d endured following what was then his most recent hospitalization. “I desperately feel the need to connect with other folks like myself,” he wrote, “so I can validate my experiences and not feel so damn alone in the world.” Mail poured in. A particularly lengthy note came from a kindred spirit named Jacks McNamara, who was living in San Francisco at the time. The two arranged to meet at McNamara’s apartment.

“The night we met in person, we just kind of exploded off of each other,” DuBrul recalls. Their connection wasn’t romantic, but rather, sublimely clarifying. “There were so many things about our lives that made so much more sense now that we were actually meeting each other,” DuBrul says.

It was in this sense of clarity that a question arose: What if others could connect the way the two of them had? What if there was an online forum designed specifically for people with mental illness, where they could share their experiences and provide support for one other during particularly difficult moments? In 2001, forums of this sort hadn’t yet pervaded the internet. Consumed by the prospect of such an online community, DuBrul and McNamara spent the midnight hours trading ideas about how to build it. By sunrise, DuBrul and McNamara had devised a plan. They decided to call their online community The Icarus Project.

Initially, the Icarus Project existed exclusively online — as a collection of discussion threads, each dedicated to a specific topic within the larger context of mental health. On one thread called “Give Me Lithium or Give Me Meth,” people from all over the country wrote about the allure as well as the danger of self-medicating. These conversations allowed Icarus members to share details that would’ve disturbed and alarmed friends, family, and medical professionals. Icarus offered a level of understanding members didn’t get from psychiatrists.

As the number of people regularly posting on the site grew, DuBrul and McNamara saw an opportunity to expand Icarus in a way they hadn’t thought possible. They oversaw the creation of Icarus chapters in cities across the country, and eventually set up an office in New York, in a spaced provided by Fountain House, a mental health organization.

In 2007, shortly after they settled into their new offices, Icarus partnered with New York University, who called on them to help build a more robust mental health support network on campus. A year later, in June of 2008, Bellevue Hospital invited DuBrul to speak to a room full of psychiatrists about his vision for a more intimate, patient-centered model of mental healthcare. But as Icarus continued to grow and his commitments as an activist — giving speeches, traveling to host workshops — abounded, DuBrul began to feel weighed down by the stress. He wasn’t sleeping and he certainly wasn’t phoning it in.

In July, DuBrul again fell into psychosis. He was shirtless and shoeless, standing on the rooftop of an apartment building on 34th Street when the police surrounded him. People in neighboring buildings had seen DuBrul from their windows, smashing a satellite dish with a cinder block, and reported him. “It was broadcasting an alien signal,” he told the police, “so I started broadcasting my own signals.” They handcuffed him and rushed him to the hospital.

DuBrul refused to cooperate with the doctors. He swatted trays of medical supplies, hurled garbage cans, and shattered a mirror. Finally, the hospital staff strapped him to a bed and sunk a needle into his side, injecting him with Ativan and Haldol (a sedative and an antipsychotic).

Hours later, his mind still clouded in a chemical haze, DuBrul scanned his hospital room. The sting of its antiseptic-white light was familiar, but as it rushed in, it flooded his body with a hopelessness that was, somehow, new. The previous eight years had been the most productive and fulfilling of his life, and so this hopelessness was suffocating. Boxed inside the four sterile walls, DuBrul could hardly imagine what his life would look like going forward. The hours swelled into days.

* * *

DuBrul was released from care that August, and at 33, he was back to square one. This time, he made his way to Manhattan’s West Side, where Fountain House offers housing for people trying to get back on their feet after coming out of the mental health system. They offered to put him up for a while. In his journal, DuBrul tried to cobble together a path forward. “I’m reevaluating my entire conception of what it means to be a… productive person in the world,” he wrote. “I paid lots of lip service to change before this breakdown, but now I have to do it.” He was referring to personal growth, but he was also hinting at his insecurities about his success as an activist. All of those plans he’d dreamt up for Icarus, they never had a chance to see the light of day.

And now, those plans were rendered useless. The Icarus team asked DuBrul to step back from his responsibilities — he had alienated them in the days leading up to his psychotic break, and even though they would always be there for him personally, they didn’t think it possible to carry on as colleagues.

Desperate, DuBrul decided to do what his first psychotic break had made impossible: he was going to get a college degree. So he applied to Prescott College, a small liberal arts school in Arizona, and got in. DuBrul moved, enrolled in classes, and subsequently spent most of his time reading about different theories on clinical practice, the history of psychiatry, and the many movements that, at one point or another, changed its course. In 2012, at age 37, he graduated.

Then, he applied and was accepted to the graduate program in social work at Hunter College in New York City. DuBrul moved back home. While taking classes, he completed his clinical internship at Parachute, a city-funded mental health organization that sends mobile response units to deal with psychiatric emergencies. DuBrul completed his master’s last May. Shortly thereafter, NYSPI offered him his current position as a peer specialist, working to overhaul the way patients are treated.

Today, DuBrul is living alone for the first time in his life. Though his apartment, just blocks away from NYSPI, is more like an activist’s personal headquarters. Resting atop a radiator and leaning back against the wall in the living room is a corkboard dressed in a patchwork of index cards. In the corner of the room, there’s a round, oak table; piles of paper double as its cloth. For previous tenants, the room might’ve included a television, but for DuBrul, there’s no space for entertainment. “I don’t even really know how to do that,” DuBrul says, “or it feels like a waste of time.”

His favorite part about the apartment is the view — it looks out onto the George Washington Bridge and the Hudson River. “The bridge is the defining feature of this neighborhood,” he says, taking in the view from his window. To his side, there’s a bass guitar propped up by a stand. Its black surface doesn’t appear to have collected a speck of dust. “It’s incredibly punk what I’m doing now — I’m actively changing the mental health system.”

Shares