Not long ago I heard my son, speaking from a stage to an arena filled with fans, drop the f-bomb three times in one sentence, each time using the oft-censored word as a different part of speech. A record, perhaps?

At one point in my life I would have found this shocking; my funny, cheerful son had never used that word, or any other on the “censored list,” around the house while he was growing up. I certainly never did. In fact (and I don’t say this to brag, just to set the record straight), I’m the only person in my family or circle of friends who can be described as a complete language purist (or prude, depending on how one looks at these things). My father, mother, grandmother, aunt — all my early influences — felt quite free using words they would not allow in my vocabulary. Somehow, though, the words in question held no attraction for me. I thought they sounded angry.

Why do some words qualify for the “banned” or “censored” lists? Do they indicate a lowering of standards? A lack of education? Rebellion against society’s rules and norms? Or is there a power in shock value?

I love words. I appreciate the degrees of meaning attached to them. When I was teaching, I sold that primarily as a way to improve SAT scores, but I always knew there was more being expanded and improved than test score numbers. I introduced 20 words a week, required that my students use the words in many ways, tested every week on the list and gave extra credit for bringing in the words from their lists that they found in books, magazines and newspapers. Then, at the end of the year, a separate vocabulary final exam tested the entire list. My students really knew those words.

The f-word was not on those lists.

But it’s everywhere else. When a band member greets me backstage with “It’s so f***ing great to see you,” and then instantly gulps an apology, I have to laugh. I’ve said a million times, “Please don’t apologize. Use the word; don’t use the word. It doesn’t matter. Just don’t apologize for it. I can take it.”

Other word crimes bother me more. Beginning sentences with “so,” incessantly using “like.” And adverbosity, the blatant overuse and misuse of literally, totally and actually.

The best language is clear, forceful, taut, and often accompanied by wit. It engages the listener and therefore communicates the message. It does not offend.

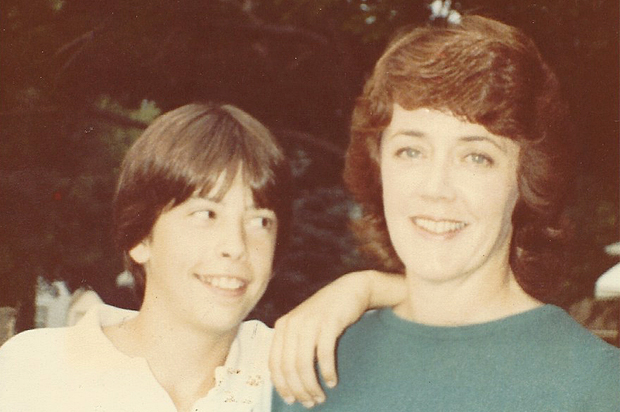

Perhaps, then, the best short speech I’ve heard this year was delivered by Mary Morello, the mother of Tom and a veteran activist who has won national awards for her anti-censorship efforts. She was defending hip-hop and rap groups long before her own son began delivering strong, anti-establishment messages with his band Rage Against the Machine. Mother and son continue to rage, and I was in the audience at the Forum when Mary took to the stage at a recent show. Grasping her walker, she slowly walked to the microphone, whereupon she opened the evening with this:

“Hi, I’m Mary Morello and I’m 92 years old.” Then with her arm raised in a power salute, she said, “I’d like to introduce you to the greatest f***ing band in the universe!”

And I joined in the standing ovation.

On my 92nd birthday, I’d like a big cake with the f-word, used as three different parts of speech piped in lavender frosting across the top. I promise an appropriate response.