“I don’t think the structure of the human skull is to be blamed for man’s inability to understand the concept of infinity.” –Mileva Marić

All of history is successful propaganda. Central to this propaganda is the care and advancement of the Great Man, the axis on which Western culture continues to crank out its familiar tropes, a form of intellectual feudalism necessary for the care and advancement of the Great Man narrative: He was bad to women! He was crazy and mean to waiters! But he was a genius so we forgive him! Regardless of how unfun it may have been to serve the Great Man’s intellectual or artistic estate — or minimize one’s own intellectual property rights therein (see also: Tolstoy’s wife and her eight epic rewrites of “War and Peace”) — one fact continues to emerge in popular culture: genius is a singularly white male phenom and as such it continually regenerates, feeding on its own PR like the worm Ouroboros.

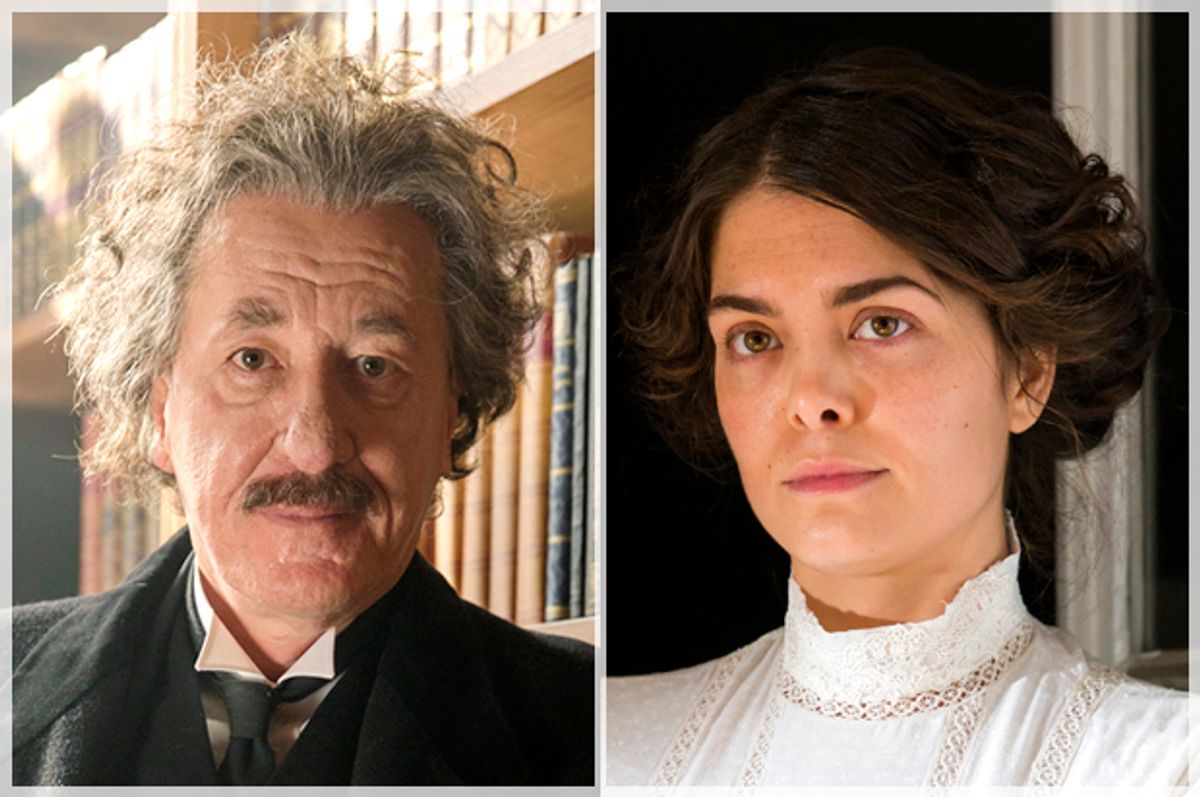

What is often left out of this narrative, and what “Genius,” a compelling 10-episode series on Nat Geo about the life of Albert Einstein, reintroduces is the revolutionary concept that women are geniuses too. What? In fact, there may have been another smartypants, or in this case, smartyskirts in the E = mc2 mix. Case in point, Mileva Marić (played by Samantha Colley), a Serbian physicist with a congenital defect of the hip to whom Einstein was married from 1903 to 1919 and who may or may not have co-authored some of his important early theories, including his theory of relative motion.

“We were aware of the archetype of Einstein as the stringy-haired genius on a bicycle,” says Sam Sokolow, executive producer of “Genius” along with Jeff Cooney. The series is based on the book “Einstein: His Life and Universe” by Walter Isaacson. Biopic specialist Ron Howard also directed the first episode, which features Geoffrey Rush as older Einstein. “It was a real opportunity to do a real exploration of the man and the people in his life,” Sokolow continues. “Not just the stringy-haired guy and the a-bomb.”

“Every genius is flawed or challenged in some way,” producing partner Jeff Cooney adds. Though the team has yet to make a final decision about which genius will be the subject for Season 2, names of world-changing luminaries from “Tesla to Prince” are in discussion.

In the first two episodes, women and physics hold the greatest sway over Einstein’s mind, heart and loins. When we first meet Older Einstein, he is lustily schtupping a hot assistant against a blackboard covered with physics equations. When Young Einstein (Johnny Flynn) fails out of high school, which is somewhat heartening for us normal folk, this folly will deliver our accented autodidact to sweetheart #1 who, as luck would have it, is not only lusty but also super hot and good at French, though sadly not so into talking about electromagnetic thingamabobs. Meanwhile, his second wife, cousin Elsa Löwenthal (Emily Watson), looks frumpy and foreboding if somewhat un-Jewish, as she reports that first wife Mileva has been calling all morning and then begs Older Einstein not to retreat into his books. Women! Books! Everyone vants a piece of the white male genius!

Thankfully, women and physics magically meet and mate in both the real-life and the fictionalized Mileva Marić. In Episode 2, we see young Einstein and Marić as students together at Zürich Polytechnic. There they are, Dolly and Johnny (their pet names), in their underthings, languorously splayed across a book-strewn floor, doing the 1897 version of Netflix and chill (her hair tumbles, loose and free, like an eighties shampoo commercial). For a time, the two historical lovers were inseparable, and their early letters indicate both passion and whimsy as well as heated intellectual exchange. Their later letters are sadly marked by rancor on his part and a desperate need on hers.

“Einstein, Chaplin and Babe Ruth all exploded onto the scene at the same time,” Sokolow says. “Einstein was the first internationally famous genius and mass media certainly played a part in this. Science was considered the wave of the future. He’s worthy of the great man allegory but we were thoughtful to represent all characters for their contributions.”

“Every genius is flawed or challenged in some way,” Cooney adds. Of course, we all have our flaws and Einstein had his — he was a love addict who didn’t believe in monogamy and he was given to fits of great pique — but he kept all of his big, blue marbles, unlike his ex-wife or, say, John Nash, the Nobel laureate who Ron Howard immortalized as a troubled math kookster in his 2001 film “A Beautiful Mind.”

That said, while the world carried him forward, it did not do the same for Marić. I won’t give too many spoilers here, but when real-life Einstein and Marić both failed their final exams at Zürich Polytechnic, the board of examiners changed his grades to pass but not hers. Subsequently, when Einstein’s parents, who weren’t such fans of the non-Jewish, congenitally lame Marić, ordered real-life Einstein home from Zürich, he sent his Dolly a letter that said, “I’ll be so happy and proud if we are together and can bring our work on relative motion to a successful conclusion.”

Our work. Just saying. Then all sorts of life happens. Later, Einstein ends up giving Marić all of his Nobel Prize money. Not irrefutable proof she co-authored, but still. They were inseparable. They were study-buddies. They were, quite possibly, equals.

“In this 10 hours, he’s not the only gifted person,” Sokolow admits. “Mileva’s intellect is given a lot of credit in this piece.”

“In order to tell the most truthful story we had to be careful that it was intellectual and respectful,” Cooney adds. “It happened at a moment when Einstein was catapulting into fame and recognition and when she was under societal pressure to be a mother and a wife -- but she’s also a force so their relationship is intense and unique.”

Toward the end of their real-life relationship, let’s just say that things devolve for the couple, as they are often wont to do when you marry yourself a genius. “You did make me laugh aloud when you threatened me with your memoirs,” Historical Einstein wrote to Marić on Oct. 24, 1925, leading to some conjecture regarding the nature and level of her input in his early work. “Doesn’t it occur to you that no cat would give a damn about such scribblings if the man you’re dealing with had he not achieved something special. If one is a zero it cannot be helped, but one should be nice and modest and keep one’s trap shut. That is my advice to you.”

Nat Geo’s “Genius,” might not topple the monolith — it’s not “Mileva: The Musical!” — but it posits the crazy idea that alongside the pillar of modern physics is his female equal whispering “gravity, gravity.” Through Marić, we witness the myriad obstacles, often insurmountable, that female scholars faced at the turn of the century, the massive emotional drain of serving the male personal myth and the toll it took on Marić’s own career advancement and mental well-being. Indeed, her genius was left to rot on the altar of domesticity while Einstein’s was allotted a harem, a fan base and a support staff. In the end, one legacy fades to darkness, while the other becomes indivisible, particulate light.

Shares