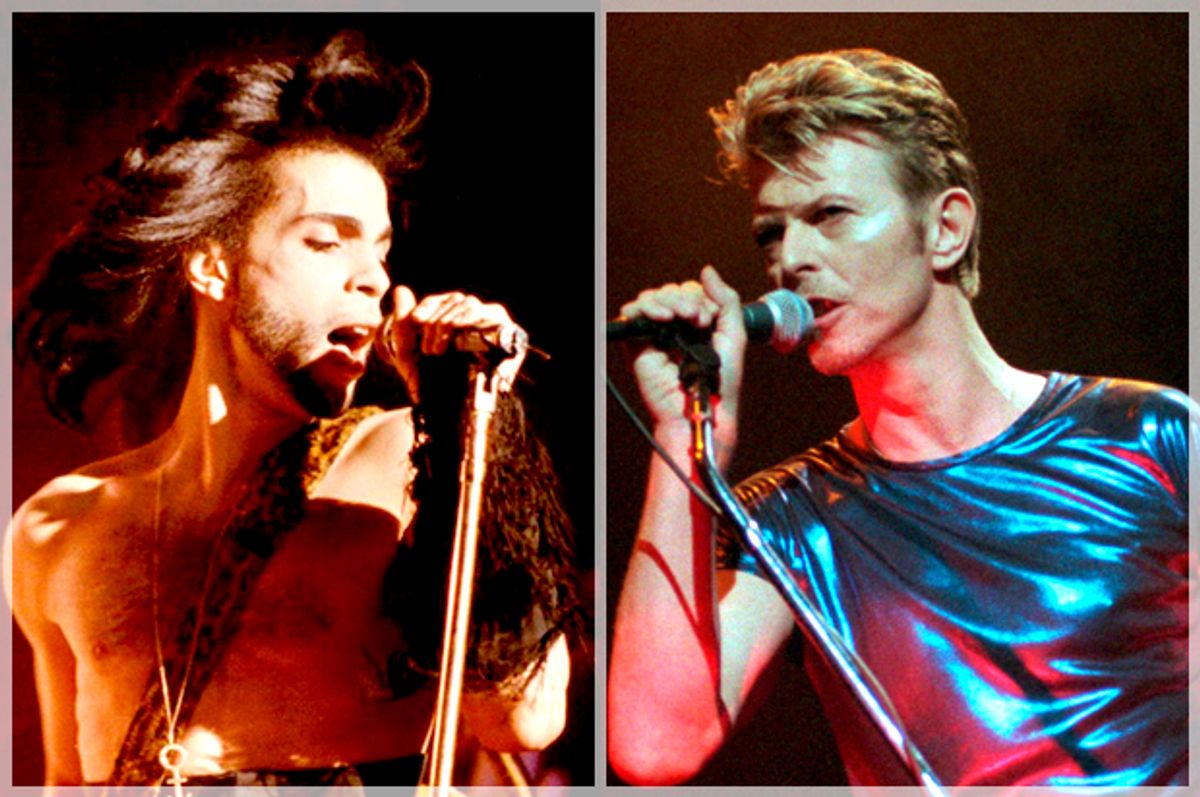

On the surface, talking about loss collectively through social media perhaps ought to be seen as a good thing. Bringing grief into the foreground of the cultural landscape might be seen as an antidote to the greater and more prevalent tendency to avoid addressing death directly. Letting others share in your grief can be viewed as a step toward recognizing how integral loss is to life. With the pressures to remain eternally optimistic that bombard us on a daily basis, it might seem as though carving out a little time to be blue together — even if only virtually — is a small act of civil disobedience. And this feeling of disobedience (a small rush, a tiny comfort) might be specially significant for those who reached out to their online communities and strangers alike with personal anecdotes of feeling queer and closeted until the likes of Bowie, space alien and lover, came along and shed a little light into those shadows. Or, likewise, the lonely hearts who wrote about the ways in which Prince — a black, gender-warping man from Mormon Minneapolis — recast for them what it meant to be in one’s own body and to find some bliss: "legit changed my life hearing prince say 'im not a woman. im not a man. im something you will never understand,'" wrote one Twitter user, @fijiwatergod, while another, @yung_nitsua, reflected that "Prince was the first person who made me feel like it was maybe possibly ok to stand in my masculinity a little differently." Comedian Aparna Nancherla gestured to Prince’s otherworldliness without slipping into the more common death-denying narrative that prevailed online: "I think we all knew Prince would leave the party before it got lame, even if it was his party."

When an icon like Bowie or Prince dies, there is a rush on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, to be the first to announce it. Without taking a moment to think of the life extinguished, users post and retweet the news of a celebrity death as though beating others to it means tapping into a virgin trove of social capital. Twitter and Facebook profit off our engagement on their platforms — that is the exact premise of their business — and they do so best when that engagement is at its shallowest. When death starts trending, we witness information capitalism in action. And so it was that an adoring and voracious public eulogized these men online and off: through candid fan interviews airing as part of 24-hour news coverage of their deaths, to streetside memorials, to the retweeting of other musicians’ pithy goodbyes, to film-screening tributes, and more. Lyrics were shared, memes created — the Internet gave way, if for just a short while, to tenderness. But it also did what it does best, giving us the tools to measure and compete in our tendernesses. Who was feeling these losses the heaviest? Who was carrying Bowie’s or Prince’s lyrics with them the most? Whose grief was the most likable, shareable? The attention economy does not make room for the laborious undertaking of embracing and reckoning with ugly feelings, and so social media trades on grief as though each post, each tweet, were a step in the grieving process and not an elision of that very process.

In this spirit, Lady Gaga — preferring ink to digital characters — had the cover of Bowie’s 1973 album "Aladdin Sane" tattooed onto her left ribs. She documented the process on Snapchat for good measure, and later dressed like Ziggy Stardust to a Grammys after-party to honor the late rock star. These acts served to foreground and reiterate how important Bowie was to Gaga, who wanted to demonstrate the intimacy she felt with the late singer. Even if that intimacy was one-sided. To some people (including one of Bowie’s former band mates, and the rock star’s son), these gestures of tribute and their documentation on social media came across as Gaga capitalizing on Bowie’s death, invoking his name and inking his face onto her body as a way of amalgamating his fame with her own waning status as offbeat icon.

And yet, it might also be worthwhile to consider the ways that grief can be simultaneously felt and performed. Not all grieving needs to be experienced alone, cloistered in the dark. Gaga’s need to wear her grief on the surface of her skin does not automatically make that grief superficial. The boldness of her broadcast sorrow makes me think that perhaps she is not unlike Sophocles’s rabble-rousing Antigone, who symbolizes grief in both feeling and action. It might be tacky, it might be tender, it might be strategic — or Gaga’s grief might just point to the contradiction of modern mourning: a compulsion to rapidly articulate that which is so hard to put into words. Bonus if that articulation doubles as shareable viral content.

The trouble with the iteration of mourning we can find online is that compared to the important work of eulogizing a life, it is but a quick fix to what is perceived as the problem or bad luck of death. What’s more, the user who gets to the keyboard first and breaks the news is transformed by her timely tweet into Top Griever. Top Griever becomes a personal news source to others who can turn to her for the best archived photo of Bowie, of Prince, and retweet that to their own followers with the comfort of knowing that the grief content they are sharing has been vetted.

While there is comfort in being a part of the conversation, feeling a part of something bigger than yourself, there’s also something socially compulsive about the rush to memorialize a dead celebrity online. A hint of surveillance; a whiff of the hegemonic. When there is a compulsion to commemorate and to profess one’s sadness in the wake of a famous figure’s death, online mourning becomes just another script we are meant to follow.

To hashtag-RIP a celeb you saw in a movie 20 years ago because that’s what the well-branded avatars you follow online are doing is not to grieve. It is to perform a version of grief that carries with it some virtual currency, some sense of social cachet. Grief is performed on social media as part of an unspoken competition to grieve the most beautifully, eloquently, and intimately across platforms. This intimacy is illusory. To be clear, not all intimacy produced through social media is imagined; affinities are discovered and bonds forged daily and even lastingly through the Internet. But an intimacy arising from public performances of grief is an intimacy run amok.

Shares