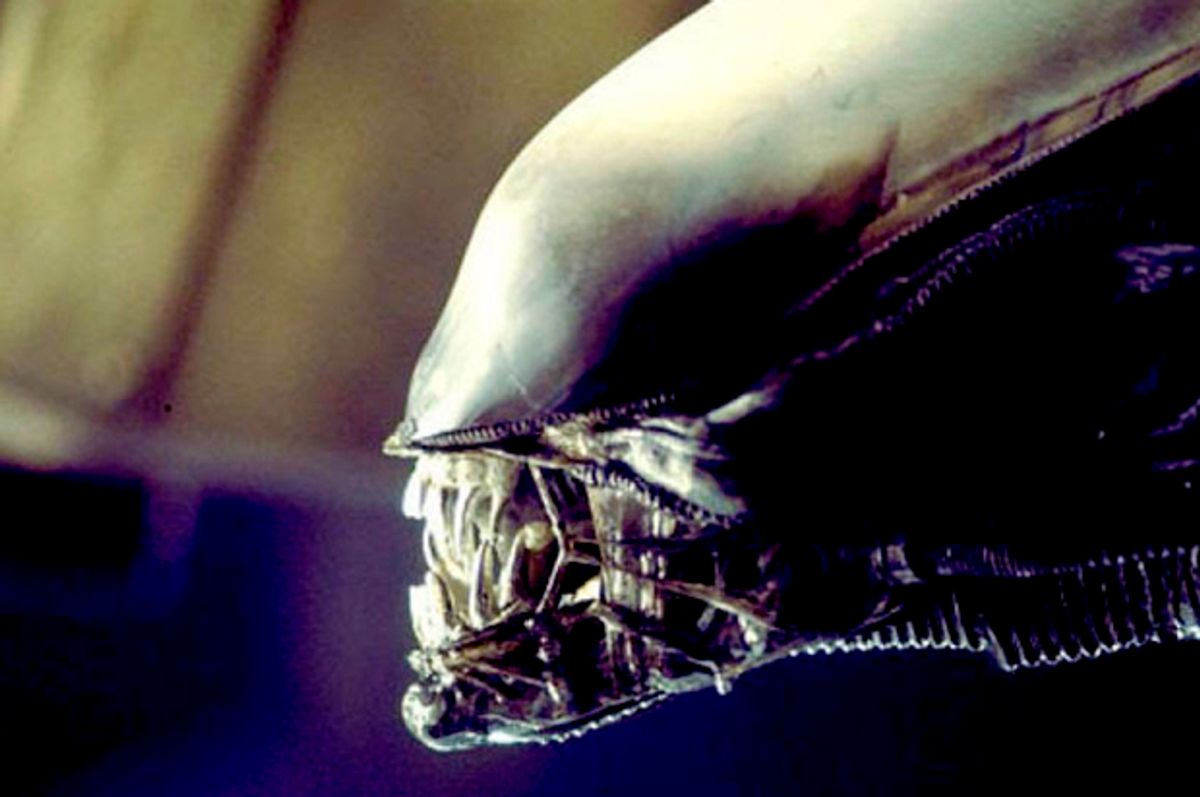

Director Ridley Scott’s “Alien” science fiction horror film franchise continues with its sixth installment that debuts in U.S. theaters this week. “Alien: Covenant,” the second prequel in the series, picks up years after the events depicted in the 2012 film “Prometheus,” in which a small group of explorers from Earth is sabotaged by a relative of the intelligent, acid-bleeding space monsters first introduced in the 1979 original.

Along with Parkour-adept parasitic extraterrestrials, a common thread runs through Scott’s “Alien” films: In his universe, space activity is a private, commercial enterprise. The first film takes place on the Nostromo, a commercial cargo transporter named after a 1904 Joseph Conrad novel centered on a fictional South American private silver-mining concession. In the subsequent films we learn the back story that Nostromo was owned and operated by the fictional Weyland Corporation, an intergalactic mining company focused on terraforming planets for profit that wants to capture, study and weaponize the aliens.

Unlike Scott’s 2015 feel-good space film “The Martian,” which is focused on scientific research and intergovernmental cooperation for the advancement of science, the “Alien” films depict a grimmer, for-profit take on space exploration. Even without the monsters, outer space from this perspective is a dark and cruel place, characterized by blue-collar workers toiling in the outer reaches of the void on behalf of a giant soulless corporation back home on Earth.

Most of the tech industry billionaires who have founded space-oriented companies — Richard Branson (Virgin Galactic), Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin), Larry Page (Planetary Resources) and Elon Musk (SpaceX) among them — profess libertarian politics or come close to doing so. And as private space exploration increasingly captures the attention of these free-market boosters, the "Alien" movies offer a dark parable in which space becomes the final frontier of colonial capitalism

How humanity should tackle the immensely costly and potentially profitable process of space-based research, transport and exploration is something that’s only recently become a point of discussion and debate. Gone are the days of the Apollo mission, when national pride emerged from public efforts to be the first to reach the Moon or to develop Voyager 1, the first man-made object to leave the solar system. Today members of the public are as willing to celebrate private ventures, like SpaceX’s recyclable first-stage rocket, as they are to applaud public efforts like the Cassini mission to send back to Earth detailed images of Saturn and its moons.

When you talk to people involved in space policy, they’ll tell you there are currently no clear boundaries between the roles of government and the private sector. But there may soon be one in the form of distinguishing between missions near Earth and deeper space exploration, such as manned trips to the moon.

Last week famed Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin called on the U.S. government to reallocate resources toward a human mission to Mars. To do that, he said, public funds on near-Earth missions involving crews should be ceded to the private sector. (Near-Earth missions are generally defined as ones that take place at an altitude of about 250 miles from the planet's surface. “We must retire the ISS as soon as possible,” Aldrin told an audience during the Humans to Mars Summit in Washington on May 9, referring to the International Space Station, which is currently jointly funded by the U.S., Japan, Canada, Russia and the 22-nation European Space Agency.

Aldrin suggested the private sector should instead take over all near-Earth orbit space missions to free up public funds to put boots on the ground on the Moon and Mars. This is a common proposal in the space-exploration community, said John M. Logsdon, founder of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University's Elliott School of International Affairs.

“There’s unlikely to be enough money in the U.S. or other government budgets to operate both the space station and fund deep-space exploration,” Logsdon told Salon.

Certainly there wouldn’t be enough money for space exploration without allocating more funds to NASA's budget, which is minuscule compared with the $596 billion the U.S. spent on defense last year.

NASA’s fiscal 2017 budget request sought $1.43 billion to contribute to the maintenance of the International Space Station plus an additional $2.76 billion for transportation to and from low-Earth orbits, mostly to deliver payloads to and from the space station. That’s roughly 82 percent of NASA’s proposed budget for science expenses (which excludes operational expenses). Passing these costs to the private sector would therefore free up billions of dollars in NASA’s annual budget for deep-space exploration.

To publicly fund both near-orbit and deep-space operations would require a massive increase in public allocations, which is unlikely to happen in the current political climate. President Donald Trump’s fiscal 2018 budget proposal spares NASA deep cuts but reduces its budget by 0.8 percent, to $19.1 billion, while continuing to expand public-private partnerships.

Robert Frost, a NASA instructor and flight controller who contributes frequently to the online forum Quora, rejects any either or notion about whether space exploration should be completely publicly funded or not, but he said it’s important to keep the public’s interest in mind for the process through government-funded scientific research and exploration.

“The role of government in space exploration is to do the things that the market can’t support, but the people agree is beneficial,” Frost wrote. “When we send a spacecraft like New Horizons to take close up pictures of Pluto, we do so because, as a people, we understand that science is important.”

Frost and Logsdon share the view that the role of governments is to set up the infrastructure and transportation systems, and in the process to collect scientific discoveries and develop new engineering techniques, such as harvesting oxygen from lunar ice.

But — and here’s the question that’s yet unanswered — what happens when these processes of discovery lead to something that can be turned into a business? How is that business regulated? What is the government’s role in ensuring the operations are safe, transparent and ultimately beneficial to the public?

The mainstream view in the space exploration community is that you hand this profitable venture off to the private sector, if there’s a business model that works, which has yet to be proved.

“We don’t know whether there’s money to be made from research or other activates on the moon or Mars,” Logsdon said. “There are a number of people who suggest that’s the case, but it has to be demonstrated.”

This is particularly true with deep-space exploration. It’s one thing to shuttle millionaire tourists into low-Earth orbit, like Virgin Galactic is trying to do, and it’s another thing entirely to send robotic miners to an asteroid and send back natural resources profitably, considering the immense costs and engineering challenges.

Current private-sector involvement in outer space is a long way from the deep space dystopia depicted in “Alien,” but it raises important questions about the future balance between the public’s interest in outer space and whatever businesses can be built out of publicly funded space exploration.

In many ways this not much different than the debates we’re having today here on Earth regarding a broad range of issues about the roles of government and private institutions, from the handling of public education to the privatization of prisons. The question is whether we want to transfer this debate into a distant and dangerous environment where companies may not be as accountable for their actions as they are (or aren’t) on Earth. To paraphrase the original “Alien” tagline, when something goes wrong out there, nobody can hear you scream.

Shares