A woman in motion is a powerful thing. Perhaps that’s why her ability to go forward independently is always subject to concern and criticism. She walks down the street to a chorus of catcalls. She drives down the road, knowing that in other countries that right is restricted. And she runs, her sneakered feet treading a path generations of other women fought for her to pound.

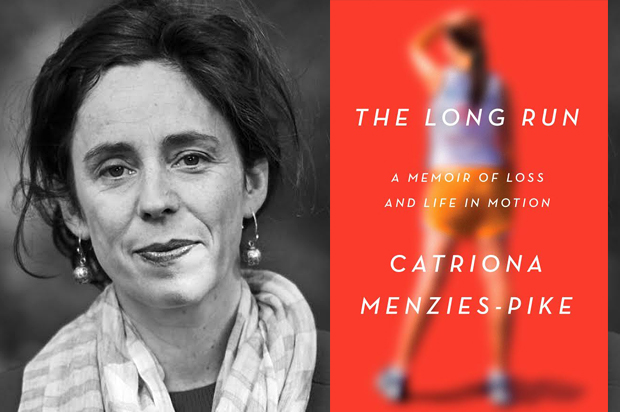

Australian writer Catriona Menzies-Pike is an unlikely marathoner. Yet in her insightful and intimate new book “The Long Run: A Memoir of Loss and Life in Motion,” she traces her own evolution as a dedicated — if not especially athletic — runner who came to the sport during the long grieving of her parents’ untimely death. She also uses this journey into the self to explore the hidden history of women as runners — the decades of concern trolling over their health and safety, the outright opposition to a pursuit so ostensibly unladylike.

Salon spoke recently to Menzies-Pike about women, endurance and the secret history of women in running.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways in which running has transformed from being thought of as a very masculine pursuit to being considered really much more feminine. It’s so much about the way that women’s mobility has been hampered historically and how the notion of women being able to literally move freely has been so repressed.

Yeah, I started running in Sydney. It’s a city full of women runners, but 30 years ago that wouldn’t have been the case. There are also the places around the world that you can visit where it’s not possible for women to go out running in the way that you do in the park across the road from your home, or the way that I do.

There’s a flashback scene early on in “The Handmaid’s Tale” of Offred and her friend just running freely through the street. They’ve got their headphones in but you can see people glaring at them. I’ve had experiences running through New York City where I’ve been training, and if you’re running in the early morning and you’re in your shorts and you’re in a sports bra, the sense of judgment and danger is so real. In the park where I run, a runner was murdered and the crime’s never been solved. It makes me think of all the danger to women as well as this empowerment that we have when women run en masse. There’s a freedom we don’t have as much when we run as individuals.

I think you’re right. There are these feelings of being more conspicuous, especially if you’re running alone. For some women that’s not a big deal, but I’ve spoken to so many women runners who say, “I get uncomfortable running after dark in new places.” I don’t think it’s anything any woman runner wouldn’t have at one point asked herself — questions about safety and visibility in public spaces. How do you square that up against this tremendous feeling of physical power? Being fit and being fit enough to run for an hour is a really amazing sensation. The feeling of vulnerability that trails a lot of women runners is a strange companion to that feeling of great independence and mobility.

[salon_video id="14769384"]So tell me a little about the choice for you to write a book that was really about loss and grief and your personal experience, as well as one that really traces that narrative of women as runners.

Certainly the thing that I wanted to write about was the amazing history of women’s long-distance running. I came to running quite late and it’s really hard for me to explain how unlikely it was that I would actually keep running when I started. I’m a really, really clumsy runner still. I just had this mystical idea in my head about what it might feel like to run for hours.

I started running and completely loved it. I avoided any sporting history because, for 30 years, I just did not want to know anything about anything to do with sports. I started to encounter these little snippets about really famous women athletes like Kathrine Switzer and tune into the fact that the women’s marathon wasn’t run in the Olympics until 1984. This seemed to me like the scaffolding for really extraordinary feminist history. Not just because of the women who populated it, but because of the constant theme of the exclusion, because of this idea that bodies moving around in public is such a charged political topic. I just kept reading and I kept finding all this interesting stuff and I thought, “My God, this is amazing and no one’s really written about it.” In fact, the further back you go, the records become really threadbare. It’s as if officials bent over backwards not to record any data about these really brave women who defied convention to go out and do this thing that was thought at best unladylike and at worst relatively dangerous.

I started putting together some ideas about this; I started also thinking about representations of women running in film and in literature and public culture. I started to think about why I had had this antipathy to running and to think about women being scared about running in public or kind of awkward in their bodies. I was sort of hoping that I might write a book that encompassed some of the things that I felt when I started running, which was extremely self-conscious, extremely awkward, still kind of a bit repelled by the sort of rapid goal-setting of it all. I just kept circling closer and closer to the fact that that I was a really unlikely convert to marathon running, having been this kind of bookish, cocktail-drinking person. But it had really introduced big changes in my life and had set this process of grief which I’d been carrying around really heavily into motion and as I started to reflect on that and get closer to that material I realized that I needed to write about that as well. The book I wound up writing really does situate my own experiences as a runner in line with this kind of bigger set of stories about women and running, and it felt like the right path to tread.

My parents died when I was quite young and my 20s were really, really shaped by that loss and ending in a really intense denial of that horrible reality. Then suddenly, you know, you run for two hours and these emotions start to rise from places that have stayed dormant for a long time. You’re running and you’re an hour away from home, and the only thing you can do is just kind of keep going with that. For me the actual embodied experience of running was such a powerful conduit to recovery and moving forward with that, rather than pushing it away. When you’re that tired, you just have to confront some of the realities in your life — and that’s a great thing. Then you have a great endorphin kick afterwards and you eat a bowl of fruit and feel great.

What I’ve seen in just the past few years that I’ve been a runner is change in the way that running has become so much more feminized. When you do a half marathon, the number of women is extraordinary.

It suggests that the rise in the number of runners worldwide is really driven by more women running. Even in the time that I’ve been a runner I think there’s been a real expansion. There’s a whole lot of different kinds of models for women runners — not only athletes who train really, really hard and are absolutely committed but I think there’s a lot more space for slower runners. Groups for women who want to run together who are running to spend time with other women, who feel more comfortable running in groups than by themselves. I think the ways in which you can present yourself to the world as a woman runner have become much more numerous.

I was trying to figure out what the tipping point was, and I was wondering if it was when Oprah did the Chicago marathon and it was such a high-profile thing that this woman who was not 25, who was not skinny, who was not your typical marathon runner, ran a marathon. Then when Oprah does it, running is the new book club.

When someone who is a mother or older or just a woman who hasn’t spent her life devoted to training says, “I’m going to run a marathon and see if I can do it,” and they do it, there’s something really, really stirring and kind of equalizing about that. You might be Oprah, but it’s still a really long way to run and I think you can identify with that in an important way. I do think those kinds of stories are gripping, stirring.

Running is also one of the easiest things you can possibly do. All you really need is a pair of sneakers and a pair of feet or equivalent to get out there and do it. It’s not like, “How am I ever going to become a tennis player?” “How am I ever going to be a saxophone player?” If you want to run, you actually can figure out a way to do that.

That’s why I’m so amazed that this is a really, really recent phenomenon. Writing the book made me think about my mother. When she was in her twenties, women weren’t going to say, “Ah, I’m going to run a 10-kilometer run this summer.”

Those runners who were making headlines in the late ’60s, that’s really not that long ago and there were outliers. There were people who were outraged that these young women were forcing their way into these distance events. They thought it was incredibly reckless and dangerous. And then it could go, in just over a generation, from this being for renegades to being something that all sorts of people do. Everyone knows someone who’s run a marathon or run an ultra-marathon or is starting to train for a half marathon. It’s an incredible shift, and I think one that’s worth celebrating. But as we celebrate, we should think about why did it take so long for the Olympic women’s marathon to be run? In that year it wasn’t just the marathon that was closed to women but also the 10,000 meters and it was closed on this idea that it just wasn’t quite right for women. It was dangerous for women to run that distance. Now that sounds absolutely ludicrous.

What do you think it is about that? Do you think it really was a misguided concern for women’s physical well-being or is there something really, really political about a woman running?

I think that late in the 20th century, you go [away] from these claims about women’s health being used. If you look in the 19th and early 20th century, at the way people talked about women athletes generally and women running particularly, yes there’s a concern that they might injure themselves. Really, what people had to say was that these women are unladylike, it’s indecorous. It’s a very middle-class concern with modesty. I think it has to do with breasts, I think it has to do with sweat and movement. There are just numerous examples of commentators, sports officials, public figures decrying women.

When you’re running for longer, the thing that makes it challenging, aside from the physical aspect, is that part where it’s, “Oh God I’m going to have to get into my head for so long.” You can’t run a marathon and not go into some dark places in your brain.

Yeah, I’ve done some half marathons and I always found myself having these major-league emotions. At first I thought it must just be some strange thing that’s happening to me, but in fact it’s a really regular occurrence. You run for two hours, things come up and you know? It’s quite therapeutic in its own way.

What do you hope this book tells people about women, particularly as runners and our history in this unusual pursuit?

I believe that it brings that neglected history to people’s attention in the first place because I think those women athletes deserve to be celebrated. I hope it makes people reflect about the way in which we are the heirs to that history and the way things can change really quickly and how we experience our everyday lives.

I also hope that the book is read as an endorsement of the stories that don’t so often get told about running and about recovery — and those are stories about slowness, about failure, about awkwardness, about self-consciousness. I love running and I’m fascinated by running culture, but there’s a triumphalism that is the dominant mode. I think that’s really intimidating, particularly for a lot of women. I hope the book emboldens people who are intimidated by that triumphalism, that it makes a space for thinking about aspects of running that aren’t just about speed and huge achievements, that allow for the real joy of running to come to the fore.